All about wombat scat

There is a lot we can learn from poop. As unglamorous as it might seem, it can tell us a lot about an animal’s diet and overall state of health: what they ate, where they’ve been, and whether they might be carrying disease.

In fact, studying scats has inspired many scientists to tackle the kinds of questions you didn’t even know needed answers, such as whether bigger animals defecate faster or how hard penguins need to push to relieve themselves. Studying fossilised poo (called coprolites) gives us a glimpse into history and helps us understand what was going on in the guts of our ancestors, including the dinosaurs. And if all that information isn't enough, you can watch our video on viking poo.

But there’s one animal with seemingly physics-defying faeces: the wombat.

Wombats are furry, stocky, short-legged marsupials that are related to koalas. They like to keep to themselves, living solitary lives in underground burrows during the day and coming out at night to forage on grasses and other plant-based foods. There are three species, all of which are native to Australia, and all of which produce curiously cube-shaped poop—roughly 80-100 droppings every day.

Their six-sided scats are unique in the animal kingdom and raise an entirely valid question: how? Do wombats have perfectly rectangular bowels? Or is there some other explanation?

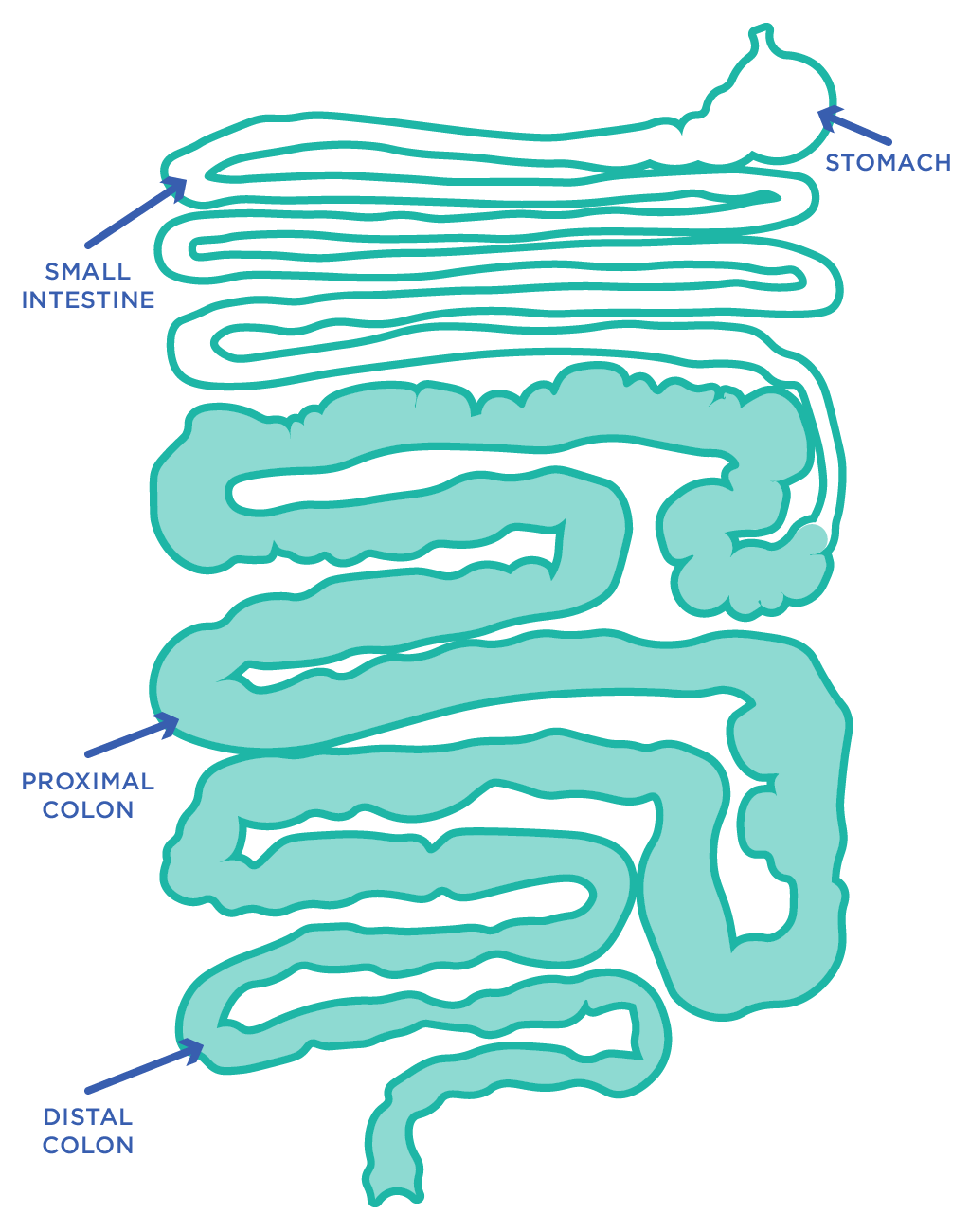

The shape of the digestive tract is very important, but not because it is somehow square. All herbivores (animals that eat only plants) have long digestive tracts—plants are more challenging to extract nutrients from compared to meat, so a longer digestive tract provides more opportunities for nutrient extraction and absorption along the way.

It takes a long time for wombats to digest their food—typically four to six days to make it through the entire gastro-intestinal tract. Wombats also have an especially long colon, the part of the large intestine where excess water is reabsorbed and microorganisms help break down food by fermentation.

There are two main parts to the colon. After winding its way through the small intestine, a wombat’s partially-digested food will first reach the proximal colon (‘proximal’ just means ‘closer to the mouth’ in this case). Here, food particles get pushed along as the circular muscles in the colon wall contract and relax. The wombat’s last meal is still fairly wet and gooey at this point.

It’s only once the digestive material reaches the distal colon (‘distal’ meaning ‘further away’) that it starts to dry out as extra water is re-absorbed back into the bloodstream. The leftover material is still being pushed along by waves of muscle contractions, but it starts to segment into dry, compressed and inflexible faecal pellets. Even as they continue their journey through the last of the digestive tract and finally make their way into the outside world, there is little opportunity for any further shaping and contouring along the way.

But how, exactly, do those pellets end up in that distinctive blocky shape? Unfortunately, it is still something of a mystery. While some have suggested that there are ridge-like structures within the colon that somehow contribute to the shape, they are most likely referring to some non-permanent structures that form during muscle contractions but then disappear as the muscles relax. These are unlikely to have any flattening effects while the waste matter is still fairly wet.

While we don’t know the precise mechanics, we can only assume that the combination of lengthy digestion time, an exceptionally long gastro-intestinal tract and very dry waste matter all contribute to producing cube-shaped poop—somehow.

This is a winning combination from the perspective of a wombat. The long digestion time and extra-long colon allows wombats to extract as much nutrition and water as they possibly can from their food. They are experts at digesting tough, fibrous foodstuffs that other herbivores might struggle with, giving wombats an advantage when the only available food in the area is relatively low quality, or when there’s not much available. Unlike other herbivorous foragers, they don’t need to waste precious energy seeking out a decent meal from further away.

The shape is good for communication, too. Wombats have terrible eyesight but an excellent sense of smell, so they use faeces as a way of communicating to tell each other who lives where and whether a female is ready to mate. They are highly territorial: a misplaced territory marker could spell disaster, so having droppings that don’t roll away is important, especially as wombats will often leave their mark outside their burrow entrances or on top of rocks and logs.

While the shape may be a bit weird, producing cubic poop has proven to be a smart strategy. Its stay-put shape makes it an effective communication tool, and the lengthy digestive process allows wombats to obtain a decent amount of nutrition from otherwise poor-quality food if they need to—proof that there’s loads we can learn from what gets left behind.