Brave new worlds: colonising (and surviving) Antarctica

As Earth’s climate has fluctuated over the millions of years of the planet’s evolution, various plant and animal habitats have been rendered uninhabitable, and new habitats have been created.

During ice ages, when the continents were covered in glaciers, many plants and animals were forced to move to slightly more hospitable, warmer latitudes towards the equator.

The most recent period of intense glaciation reached its peak—the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM)—around 20,000 years ago. In the Northern Hemisphere, as the ice melted and the extensive glaciers of this period retreated, species were able to return northwards, repopulating their previous territories and re-establishing themselves.

The story in the south is a little different though, and it’s this story that the 2018 Australian Academy of Science Fenner Medal recipient, Dr Ceridwen Fraser, is investigating using a combination of genetic and ecological information.

Antarctica and its nearby islands are surrounded by the Southern Ocean, which isolates them from the continents to the north. The strong circular currents and winds of the Southern Ocean make it extremely difficult for species to move far south as the climate warms.

Some Antarctic terrestrial species have been present on the continent for millions of years, obviously surviving the repeated cycles of intense glaciation and their thick blankets of ice. For these species, survival was a matter of finding local refugia—isolated pockets where conditions allowed them to persist. After conducting a comprehensive survey of Antarctica’s current-day terrestrial biodiversity, Dr Fraser and her colleagues found an interesting pattern.

It appears that the persistence of life on the icy continent has Antarctica’s volcanoes to thank—biodiversity is richest close to sites of geothermal activity, with increased diversity in these areas, particularly of plants and fungi.

Further away from geothermal sites, diversity declines. The geothermal activity deep underground produced localised regions of heat that were sufficient to keep pockets of Antarctica ice free—tiny patches of land, or in some regions caves, beneath the ice provided a warm(ish) haven for the terrestrial species.

Another area of study for Dr Fraser is how species migrate to new territories. The Southern Ocean is vast—it’s pretty hard to cross that much water if you can’t swim (or fly). However, some enterprising organisms have managed to ‘raft’ at least partway across the Southern Ocean, from subantarctic regions to the north.

A diverse community of sea creatures, including barnacles (Lepas australis), isopods (tiny crustaceans; Limnoria sp.), bivalves (Kidderia sp.), a sea-spider (Tanystylum antipodum), a nudibranch (Fiona pinnata) and a few species of chitons and gastropods were found to be passengers on pieces of bull kelp seaweed (Durvillaea antarctica) washed up on the Otago coast of New Zealand.

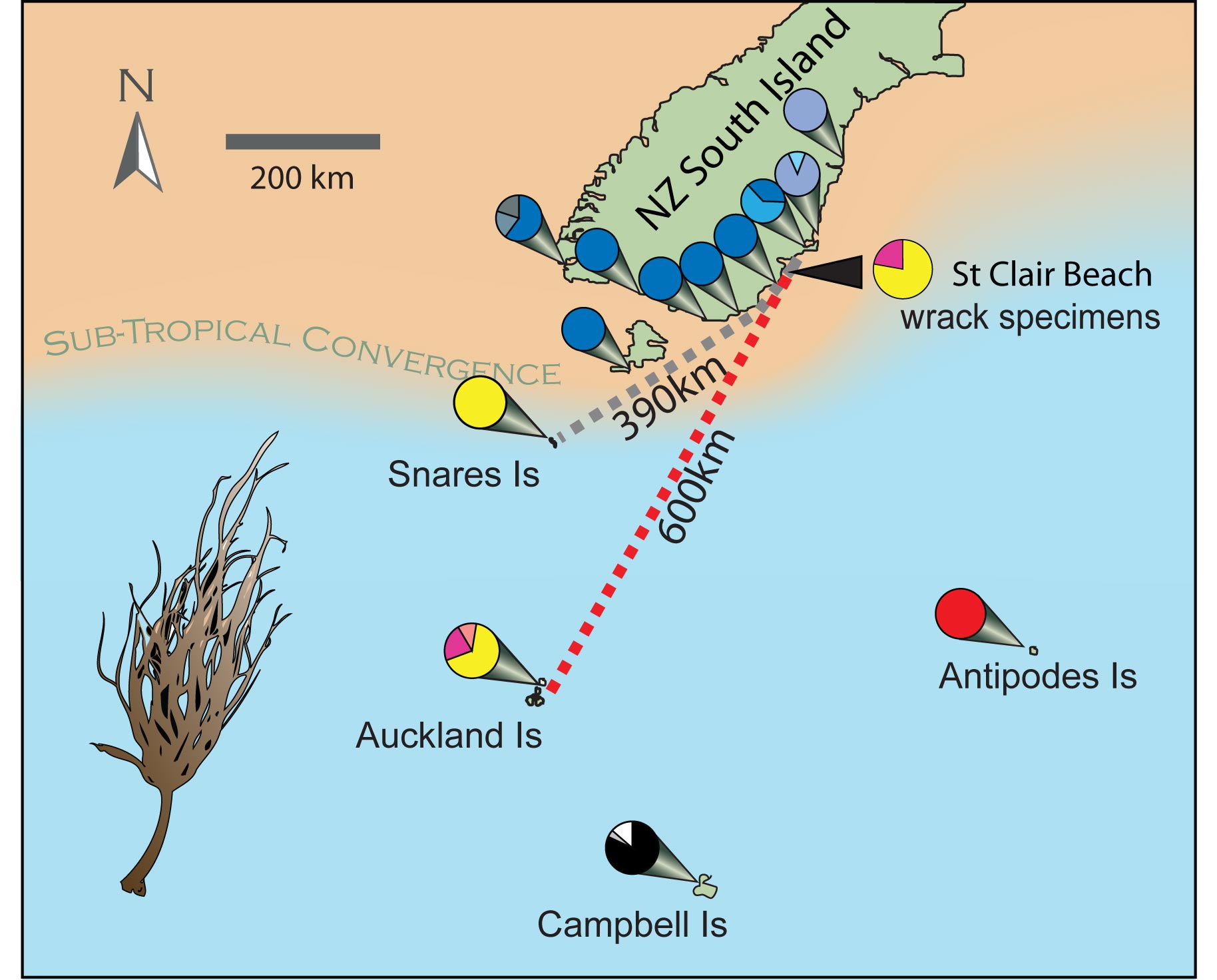

Genetic analyses of the isopods, and the bull kelp itself, revealed that they were clearly genetically distinct to mainland New Zealand species, but were a match to populations from the subantarctic, leading the researchers to conclude that both the seaweed and its hitchhiking passengers had travelled at least 390-600 kilometres, from the Snares or Auckland Islands.

This evidence suggests that complex communities can indeed raft hundreds of kilometres across oceans. What’s more, if conditions are right—for example, if there are no other members of the same species already established that could ‘block’ settlement of the new immigrants—this process can allow for the colonisation of far-distant lands, subject to the whims of the wind and ocean currents.

These are a just a few of the insights that Dr Fraser’s work has provided on the ways that climate and environmental factors influence biodiversity, and the migration and perseverance of life into new territories. As well as helping to understand the ecological history of places like Antarctica, her work also contributes developing optimal management plans for conservation of biodiversity into the future.