The super-navigational abilities of the bogong moth

Could you navigate to a destination over 1000 km away that you’ve never previously visited, without even peeking at a map? Billions of Australia’s bogong moths do just that. They migrate across south-eastern Australia to stay cool in caves in the mountains over summer, flying in the dark of the night to their alpine destination.

The life cycle of the bogong moth (Agrotis infusa) has captivated people for thousands of years. Indigenous Australians in the region traditionally followed the annual migration to eat the moths and conduct cultural ceremonies after arrival in the mountains. The moth’s common name, bogong, is derived from a local Aboriginal word and was used by a number of the Indigenous nations to describe the moths. The mountains themselves were named after them too, with some areas now known as the Bogong High Plains and the Bogong Peaks.

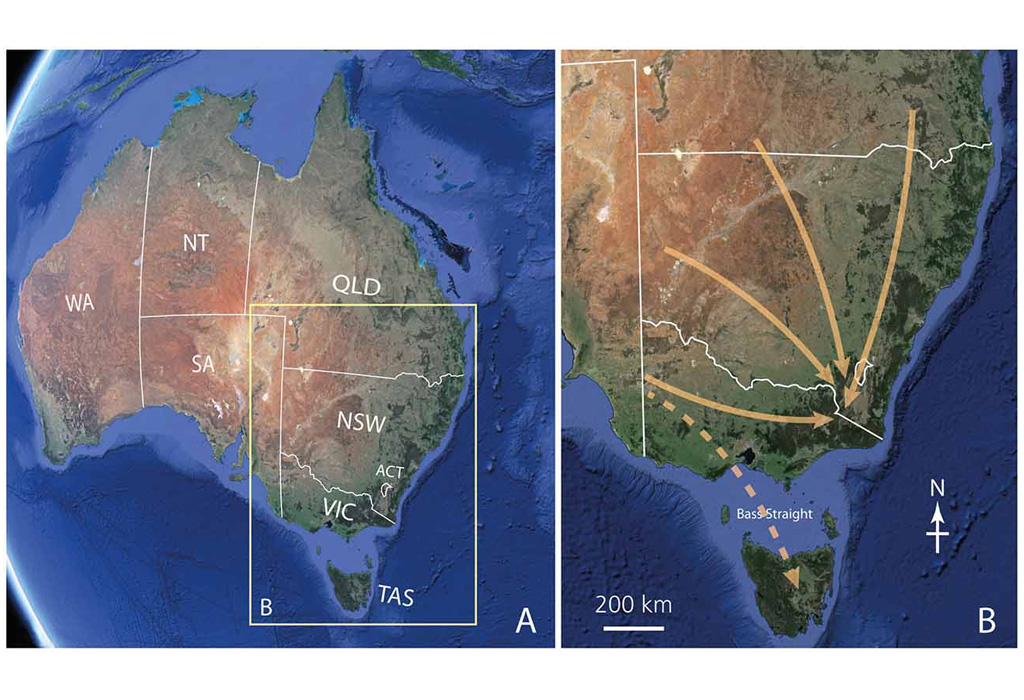

In spring, the moths travel from various parts of eastern Australia to the Australian alps, where they inhabit caves. Over the summer they go into a kind of dormancy known as aestivation. This is much like hibernation, however it occurs in some animals over hot and dry periods rather than cold. At the end of the summer, bogong moths take a second long journey and head back home. They then breed and die soon after that. It’s a short but arduous life. The following year’s big migration is taken by the next generation of bogong moths.

The big question is: how do they know where the mountain caves are and how to get there when they have never been there before? Do they somehow inherit the information from their parents? It is still a mystery as to why they choose to set off on their journey and how they know which direction to go, but we do have some insight into the way they keep their direction steady. The clouds of moths set off at dusk together; night after night they fly towards the mountains that they can’t yet see. While they might make use of winds that happen to blow in the right direction to hitch a ride, the moths can’t just trust the wind take to them there. The knowledge of which direction to go must still come from somewhere.

Professor Eric Warrant and his team have found that the secret to the moth’s navigational skills is an ‘internal compass’ which they use to navigate the Earth’s magnetic field. We know that this is how many migratory birds—and other migratory species such as salmon and turtles—find their way over extremely long distances, but the bogong moth is the first migrating nocturnal insect understood to use this magnetic mechanism.

In an experiment with bogong moths tethered to a central point in an outdoor flight simulator, the moths would consistently fly in the same direction. When the visual cues and magnetic force were rearranged in opposition with each other, the moths, which were intercepted during their autumn migration, became confused and did not reliably fly in the direction of home.

From such results we can tell that, like a person orienteering in the bush with a compass, a moth will work out the direction it needs to take using this (still quite mysterious) internal compass, then choose a landmark in that direction as a pinpoint to follow. As bogong moths are night-time travellers, the Moon or the Milky Way are useful points of direction, along with features of the landscape. When that visual cue becomes obscured or can’t be seen any longer, such as when a cloud passes in front of the stars, the moth can then recalibrate and find a new set of stars or lights to guide it. They can then switch directions for the trip back home.

Finding out about how and why animals migrate is useful information when they don’t turn up where we expect them to. Is it their navigation that is interrupted, or is it something else impacting on the population?

Recent years have seen fewer and fewer Bogong moths ending up in the mountains. Some sites, which previously sheltered millions of moths, had only a literal handful of individuals actually turn up in 2017 and 2018. This is concerning for the sustainability of the bogong moth population. It also severely impacts the broader ecosystem, such as leaving the endangered mountain pygmy possum either going hungry or needing to adapt and find other food sources.

In this case, scientists suggest droughts in the moths’ breeding regions are the cause, so the numbers are declining before migration even begins. This problem can be compounded by human development along the flight paths, where artificial lights interrupt the moths’ nocturnal journeys. Zoos Victoria is calling on people in south-east Australia to turn off unnecessary outdoor lighting in September and October to reduce the effects on the moths’ migration.

It may be an unassuming brown moth, but these super-navigators have navigated their way into the legends, cultures and hearts of Australians. We have so much left to discover about these exquisite insects and our mountains wouldn’t be the same without them.