Things you need to know about bushfire behaviour

The primary influences upon how bushfires move through the landscape are humidity, topography, wind and temperature.

The effects of ambient temperature and humidity on a fire are pretty obvious. The hotter the air temperature, the lower the relative humidity, and any fuel will likely be drier—dry fuel ignites and burns more easily. The lower the humidity, the drier the air is, again helping fuels burn as they release their moisture into the air more readily.

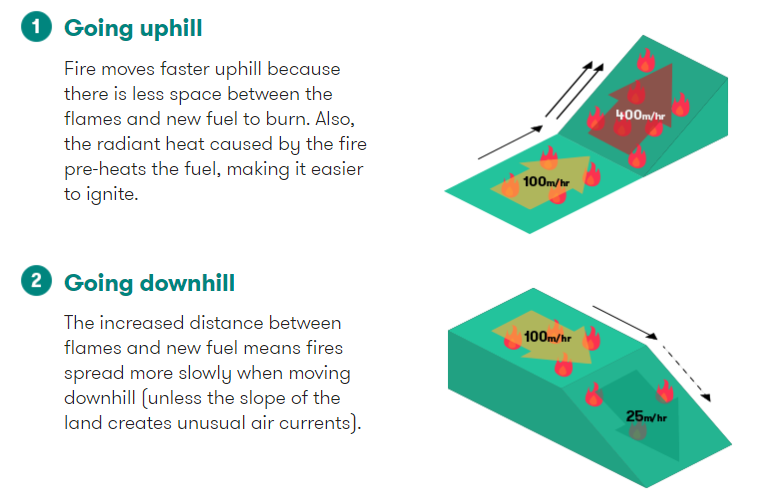

The slope of the landscape is also important. Just consider a match and how much faster it burns when you hold it so the flame is burning up the stick (and towards your fingers!) than down. Similarly, fires burn much faster uphill than down. This is because the radiation and convection a fire creates preheat the unburned fuel ahead of the flame front, and this is done more effectively upslope than down. A 10-degree increase in slope usually results in a doubling of the speed of the fire. Fire will spread up a 20-degree slope four times as fast as it will along flat ground.

Wind speed is the environmental variable that has the most significant effect on the spread of fires. With wind speeds below around 10 km/hour, a fire will usually burn slowly without a definite spread direction. However, as winds increase in strength, the rate of fire spread increases. A change in wind direction, often from a cold front, can activate the side of a long and relatively narrow fire, turning it into a very broad flame front. In general, a wider fire will burn faster than a very narrow one.

The heat of a fire can create whirlwinds and turbulent air currents. Wind is also a major factor in transporting firebrands—pieces of burning fuel, like twigs, leaves or small embers—ahead of the main fire. This causes spotting—the ignition of new fires ahead of the fire front.

When a fire becomes a firestorm

Under very dry and windy conditions, profuse spotting from certain eucalypt forests will result in the ignition of a broad area ahead of the fire. This creates a firestorm environment with highly chaotic and turbulent winds further driving fire in all directions. The mass ignition can result in the formation of large fire-whirls, or fire tornadoes. Although localised, the very strong wind speeds generated (estimated to be up to 250 km/h given the damage they cause) are extremely destructive.

If enough fuel is being consumed within the fire area, the heat generated creates an extremely strong updraught of air that can result in a pyrocumulunimbus cloud, or flammagenitus. In extreme cases this thunderstorm-type cloud can produce lightning strikes, which have been known to start new fires.