The weird thing about the malaria parasite

Malaria kills nearly half a million people every year, and research groups around the world are working to develop effective treatments.

A strange discovery, made by Professor Geoff McFadden, a plant scientist at the University of Melbourne, gave researchers a new path to follow. He discovered that Plasmodium, the malaria-causing parasite that mosquitoes carry and can transmit to humans, contains a part of a cell that is usually only found in plants and algae—a chloroplast.

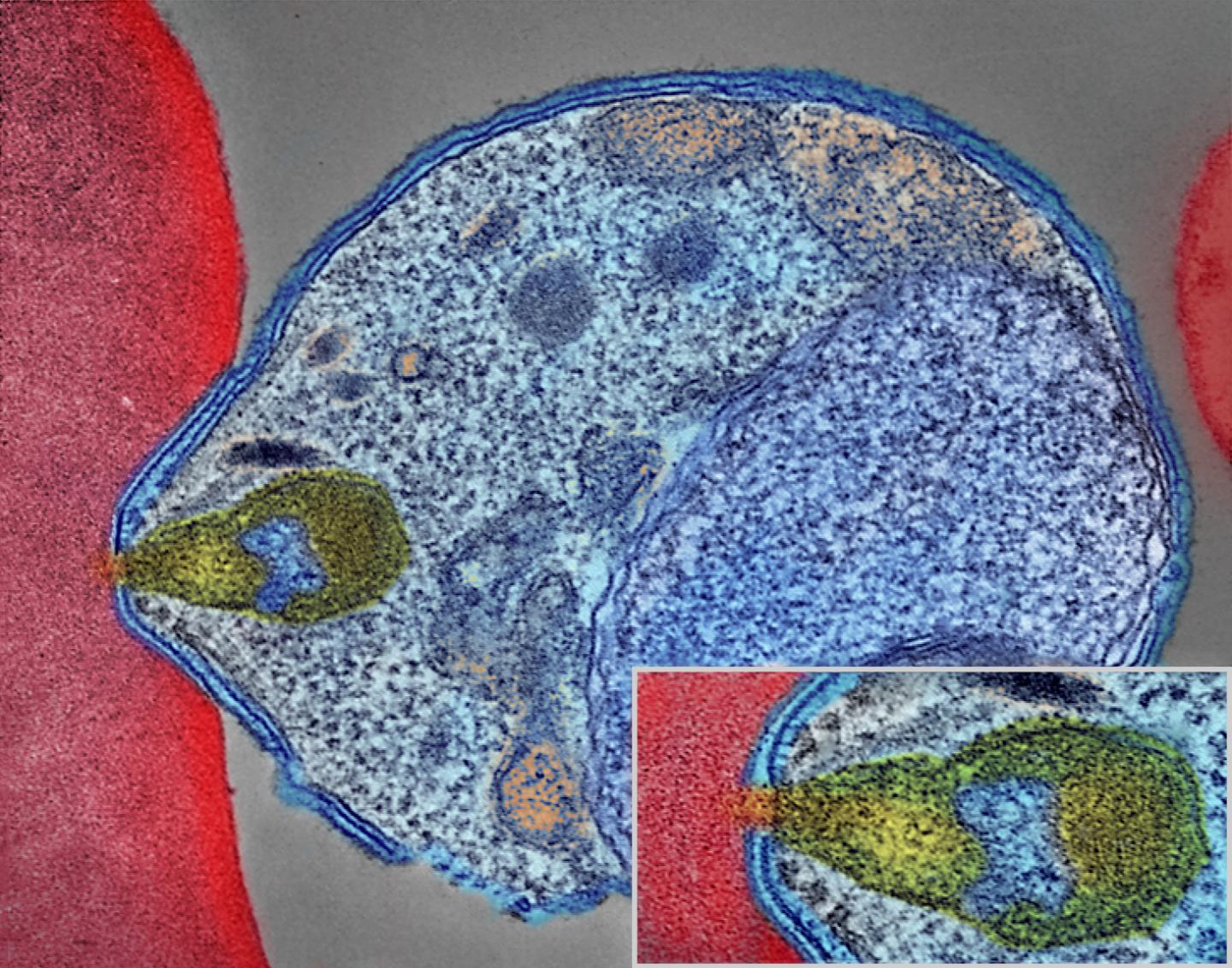

Plasmodium is a microscopic single-celled organism. McFadden and his team identified that within its single cell, the parasite has a small, relic chloroplast. In plants and algae cells, chloroplasts contain the chemical compounds that are essential for photosynthesis—the process that gives plants their energy.

The chloroplast found in the Plasmodium parasite has the same evolutionary origin as the chloroplasts found in plants. The chloroplast in Plasmodium is not used for photosynthesis today, but a long time ago, earlier in the parasites’ evolution, it probably was. It does play an important role however—it contains genes required for fatty acid and isoprene metabolism, which produces compounds essential for the parasite’s survival.

The discovery that Plasmodium was once a photosynthetic organism that somehow evolved to become the parasite it is today opened up a new way of treating people infected with the parasite. The aim is to stop the parasite reproducing while not affecting the cells of the human host. Obviously, humans don’t have chloroplasts, so a drug that targets only the chloroplast is an ideal option. Millions of people are now protected from malaria by a drug known as doxycycline, which inhibits a gene that McFadden identified in Plasmodium.

No-one predicted that malaria parasites would have a chloroplast. If it wasn’t for scientists examining the evolution of various organisms and the tree of life, effective new ways of treating malaria would have gone unexplored.