Is your laundry polluting your seafood?

If you look at the stuff around you, right now, how much plastic do you see? It’s everywhere, right? We use it to carry things, package things, drink things and type things. We’ve also seen the damaging effects of throwing away so much plastic and the harm it can cause to the animals unlucky enough to consume it or become entangled in it.

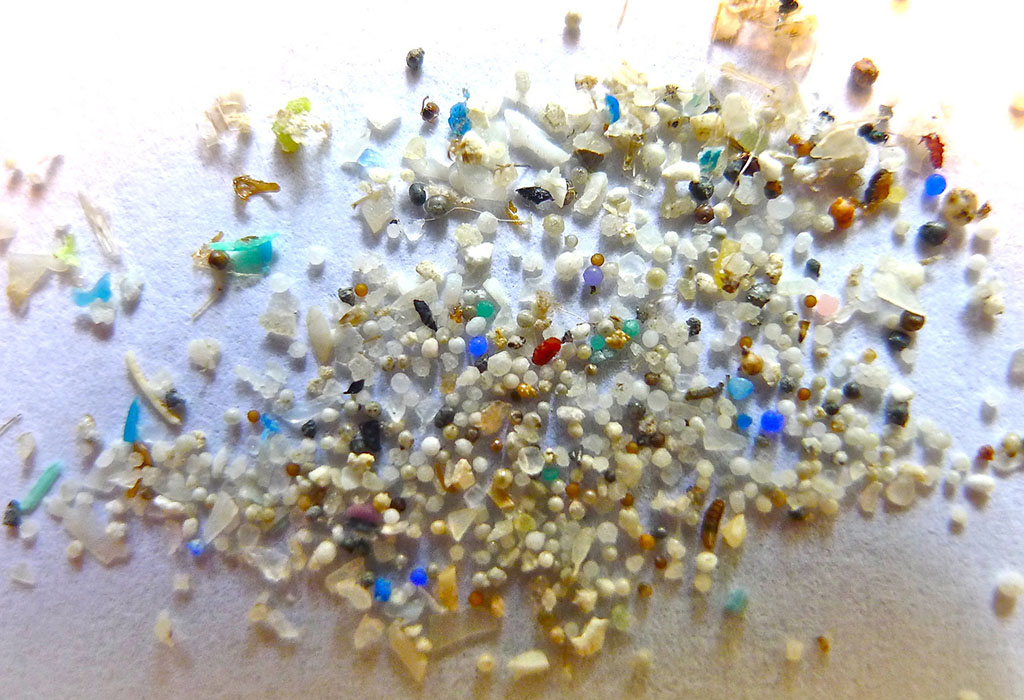

What we can’t see so easily, though, is the growing amount of microplastic pollution in our rivers and oceans—and how it can potentially end up in our own bodies.

What is microplastic?

A ‘microplastic’ is any piece of plastic smaller than 5mm in length. They may have been deliberately manufactured for a specific purpose (primary microplastics), such as the plastic microbeads found in exfoliating body scrubs and exfoliants, or they may result from larger pieces of plastic gradually breaking down into smaller fragments over time (secondary microplastics). A 2017 report by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature estimated that 1.5 million tons of primary microplastics find their way into our oceans every year, most of which is thanks to land-based activities.

Once it’s in the ocean, all those tiny plastic particles are potentially available to be ingested by animals such as plankton, clams, snails, flatworms, crustaceans and fish. If ingested, these plastics can make their way into the circulatory system, get stuck in the guts, or get stored away in the body tissues of some species. Not all plastic gets stuck inside an animal forever—most organisms have a way of getting foreign particles out of their bodies—but that can take time.

Plastics then make their way up the food chain when predators consume prey that’s consumed (and not yet eliminated) plastic. Eventually, plastics can potentially make their way into the stomachs of another top predator: humans. (And that’s not to mention the microplastics in the tap water or table salt in some parts of the world.)

It’s important to note, however, that we don’t yet know the full impact of microplastics on human health. We don’t know how long microplastics might remain in the bodies of the seafood species we consume, or what effects they have on those species, or whether any toxic substances get transported around their bodies. For example, a fish may have plastic particles in its gut, but these won’t necessarily transfer into the muscle tissue that’s typically eaten by humans. Even if we do end up eating something that’s consumed plastic, it may not be present in quantities large enough to cause us any real harm.

Consuming our clothing

An emerging source of some serious microplastic pollution is clothing. Many of our clothes are made from synthetic fibres such as polyester, polyamide, polypropylene, nylon, acrylic and others. We’ve all seen how much lint our clothing sheds when we clean the filters on our tumble dryers, but what happens in our washing machines? Where do all those fibres go?

Washing machine filters and sewage treatment systems are not currently built to filter out such tiny fibres, which is how they end up in our waterways and oceans. A widely cited 2011 study found microplastic contaminating the sand on 18 beaches around the world, representing all six continents. Almost 80 per cent of the plastic fibres from those samples were found to be polyester or acrylic, some of the most common fibres used in textiles today.

In the same study, researchers tossed some clothes and blankets in a washing machine and found that each item shed hundreds of tiny fibres per wash—sometimes even upwards of 1,900 fibres from a single garment. Lots of factors can influence how many of these fibres are shed in the wash, such as the age of the garment or the type of washing machine you use.

A more recent study, sampling fish from Sydney Harbour, found high levels of microplastic pollution in the guts of three different species of fish. Once again, the worst offending plastic particles were fibres composed of a polyester-acrylic blend, followed by rayon, a semi-synthetic fibre.

Should we never do laundry again?

Although all of this evidence points to an alarming problem for our environment and our health, it doesn’t mean we should stop washing our clothes or eating seafood. Research funded by the Australian Research Council is underway to find new ways to address the problem right from its source, such as finding ways to redesign clothing to shed fewer fibres and to develop more effective washing machine filters that can prevent microplastic fibres from entering waste water streams.

In the meantime, you can take small steps to reduce the amount of microplastic pollution you create by choosing clothing made from non-synthetic fibres, avoiding the use of cosmetic products containing plastic microbeads, and making sure that other plastics you use don’t end up escaping into the environment where they can later degrade into smaller fragments. Let's keep our oceans healthy.