How mitochondrial donation can help stop disease

29 June 2018

Mitochondrial donation is an emerging technology that could mean the difference between a healthy child and one born with life-threatening disease.

It’s estimated that 1 in 200 people carry a genetic mutation that may cause mitochondrial disease in some form. In Australia, approximately one child born every week will go on to develop a severe form of the disease.

Mitochondria are important: they’re the ‘powerhouses’ of our cells, providing the energy required for our cells to function. When there’s something wrong with the mitochondria cells can die, with consequences for the entire body—muscle, brain, heart and lung function can all be severely impacted. It’s often difficult to predict how an individual with mitochondrial disease might be affected, but it can be fatal.

Mitochondria also have their own set of DNA, called ‘mitochondrial DNA’ or mtDNA for short. This extra set of genetic material is in charge of just 37 genes, all of which are responsible for how mitochondria function. This mtDNA is separate from the rest of our DNA, which is located in the nucleus (the ‘control centre’) of the cell and encodes approximately 20,000 genes.

However, errors in this small amount of mtDNA can still cause some major problems. Unlike nuclear DNA, where we inherit one copy from our mother and one copy from our father, all of our mitochondrial DNA comes just from the mother. The mitochondria present in the father’s sperm are usually eliminated just after fertilisation.

This means if a mother has a defect in mitochondrial genes, there are no opportunities for this to be ‘corrected’ by inheriting healthy versions of the equivalent genes from the father, and all offspring are at risk of inheriting the disorder. These defective genes will most likely be passed from an affected mother to all of her children.

Because there are thousands of copies of mtDNA in the mother’s egg, her offspring may only inherit a small amount of defective mtDNA and only experience mild symptoms. Inheriting many defective copies of mtDNA, however, will most likely result in severe mitochondrial disease.

Not all mitochondrial disease is caused this way, as there are many mitochondrial proteins encoded by DNA from the nucleus and, if there are problems with these genes, mitochondria may malfunction. Sometimes, the problem might not be genetic, but instead caused by taking a drug or getting an infection that damages the mitochondria.

How does mitochondrial donation work?

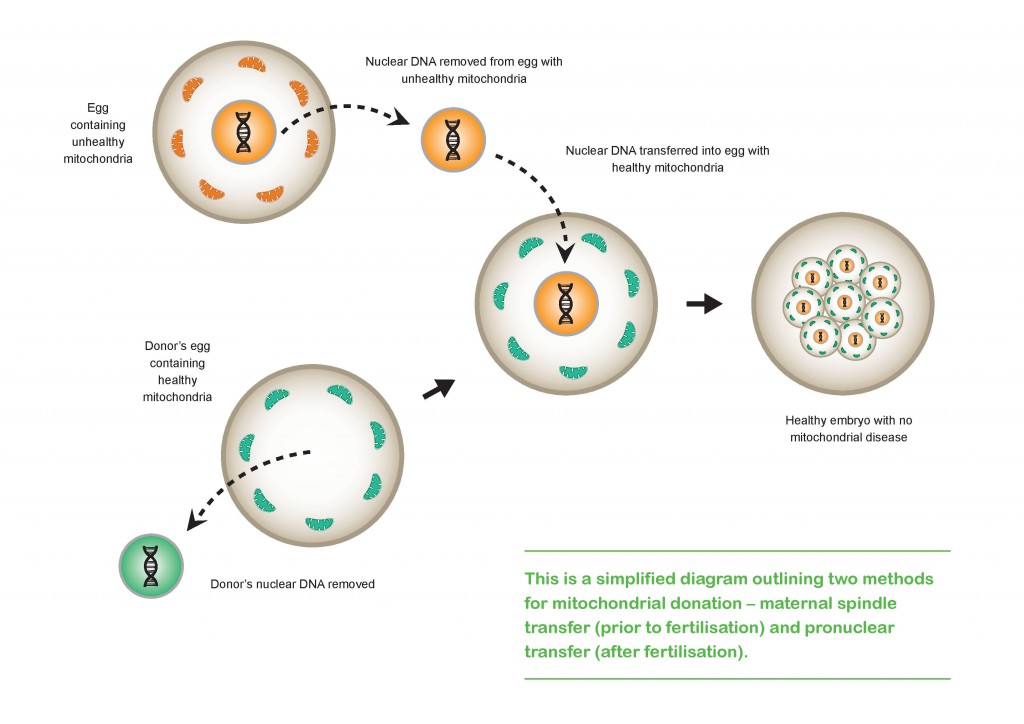

Mitochondrial donation techniques can help when there’s a problem with the mtDNA itself. There are two main techniques currently available, both of which involve transferring the mother's nuclear DNA into a donated egg with healthy mitochondria (but with the donor's nuclear DNA removed).

In maternal spindle transfer, the nucleus is removed from a donor egg (that has healthy mitochondria), and replaced by nuclear DNA separated from the unhealthy mitochondria of the mother's egg. This egg, with the mother's nuclear DNA and the donor's healthy mitochondria, is then fertilised with the father's sperm.

When using the pro-nuclear transfer technique, eggs from both the affected mother and the unaffected donor have both already been fertilised by the same father. The nuclear material in the donor’s egg is removed and destroyed, leaving an egg with healthy mitochondria but no nucleus. The nuclear material from the affected mother’s fertilised egg is then taken out and placed into the donor’s egg. This procedure is performed prior to the fusion of the male and female nuclear material, which happens just before the fertilised egg divides, bringing the parental genomes together as the fertilised egg becomes an embryo.

The end result of either technique is a developing embryo with genetic material from three separate people: the father’s nuclear DNA, the mother’s nuclear DNA, and the donor’s healthy mitochondria with their mitochondrial DNA.

Although genetic material from three separate people is involved, it is incorrect to call it ‘three parent IVF’. As well as considering the full depth and breadth of what it means to be a parent, only an incredibly small amount (0.02 per cent) of all the genetic material in an individual comes from the mitochondrial donor when the technique is used.

Mitochondrial donation in Australia

Mitochondrial donation in a clinical setting was legalised in Australia in 2022 in the Mitochondrial Donation Law Reform (Maeve’s Law) Act 2022. This legislation is named after Maeve Hood, a six-year old girl from Victoria who lives with a mitochondrial disorder.

Under the new law, the technique of mitochondrial donation will exist explicitly to prevent these diseases and will be subject to careful regulations, providing an option for parents who don’t want to pass on a mitochondrial disease to their unborn children.