Zero HIV transmissions in Australia by 2020

The Australian Federation of AIDS Organisations is hoping to put an end to all HIV transmission in the country by 2020. This is an aspirational goal but how are we going to do it when we don’t have a cure or an effective vaccine yet?

To start, it helps that Australia has a relatively low transmission rate, with an average of about 1000 new infections per year. This level has been maintained for several years, with people using the protections we’ve had for a little while now: barrier protection (specifically the appropriate use of condoms), regular testing for people who are at high risk of contracting the infection, and reducing the viral load in HIV-positive individuals with antiviral drugs.

Although these methods reduce the chances of transmission, they all have weaknesses. Condoms require individuals to use protection ‘in the heat of the moment’ and can be as little as 70% effective at preventing HIV transmission when used as the sole protection strategy in the long term; people tend not to get tested because they don’t think they’re at risk (or they’re embarrassed); and accessing antiviral drugs to reduce viral load requires individuals to know about and act on their HIV status.

This last point is a big one, because the initial stage of infection can be quite prolonged and sometimes missed. In fact, in 2015, over one quarter of new diagnoses were for individuals who were likely to have had the infection for over four years.

One of the big changes that makes the goal more achievable is the announcement early in 2018 of the HIV preventative medication known as pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) being listed on the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme. Now, Australians who are at a higher risk of acquiring the infection will have an affordable and effective preventative treatment.

Pre-exposure prophylaxis

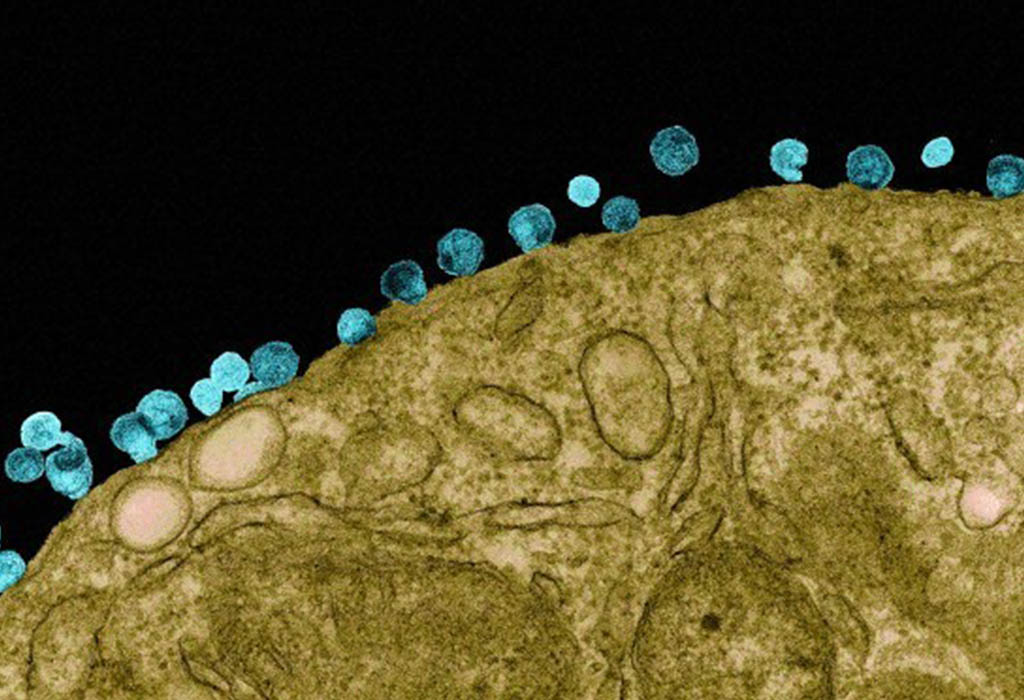

Both pre- and post-exposure prophylaxis antiviral medications take advantage of HIV being a retrovirus. This means that rather than using DNA to store its genetic information (like many other viruses, all bacteria, all plants and all animals), HIV uses a similar molecule known as RNA. For the virus to permanently infect a human cell, it needs to first transcribe the RNA into the equivalent DNA code. The recoded virus DNA is then incorporated into the human DNA and our cells inadvertently make new viral particles through the same mechanism that is used to make our normal cellular proteins.

Importantly, this initial step of converting RNA to DNA doesn’t normally occur in animals, so to get things started, the virus needs to bring with it its own special enzyme called reverse transcriptase to perform the recoding task.

The need for this reverse transcriptase is an inherent weakness and provides a drug target unique to the virus (and importantly, absent from the patient). By stopping this reverse transcriptase from working, the virus cannot replicate and therefore cannot establish an infection.

When taken properly, PrEP promises to be up to 99 per cent effective at preventing HIV infection from a partner who is HIV positive. Hopefully, with this additional protection, we can put an end to HIV transmissions in Australia by 2020.