The link between cats, your brain and your behaviour

Do you consider yourself to be a ‘cat person’? Does your ideal future involve surrounding yourself with fluffy, contented feline friends? If you’ve ever owned a cat—or been in contact with undercooked meat, or unwashed vegetables—you may be carrying a parasite called Toxoplasma gondii.

If you do, you’re not alone—roughly one-third of the world’s population is thought to carry it. This parasite can cause an infection known as toxoplasmosis, which is generally thought to cause only mild flu-like effects in most people, though it can also cause serious inflammatory conditions of the eyes.

It is perhaps most famous for some of its claimed effects on human behaviour. Toxoplasmosis infections have been associated with an increase in aggressive and impulsive behaviours, a reduced perception of risk, and an increased probability of developing psychotic symptoms (such as schizophrenia). It is possible that the parasite’s effects on dopamine (a neurotransmitter, or brain chemical) and testosterone (a hormone) may be responsible. It’s also possible that people who already have certain personality traits or brain disorders are just more likely to become infected.

It’s even been recently linked to a higher likelihood of pursuing an entrepreneurial career. Once again, this doesn’t necessarily mean T. gondii infection causes an entrepreneurial spirit—perhaps those with a lower fear of failure are just more likely to eat undercooked meat or care for cats, or there may be other outside factors involved.

However, these links are not set in stone: researchers reviewing the scientific evidence for T. gondii’s effects on behaviour and mental illness have pointed to limitations in how the data for many studies has been collected, so don’t blame your recklessness on your cat just yet.

It's also worth noting that you are actually far more likely to contract a T. gondii infection through handling or eating undercooked meat or unwashed vegetables, rather than from your favourite feline furry friend. However, cats still play a key role in facilitating the parasite's spread.

So why is this parasite thought to have such strange effects on human behaviour? And … why cats?

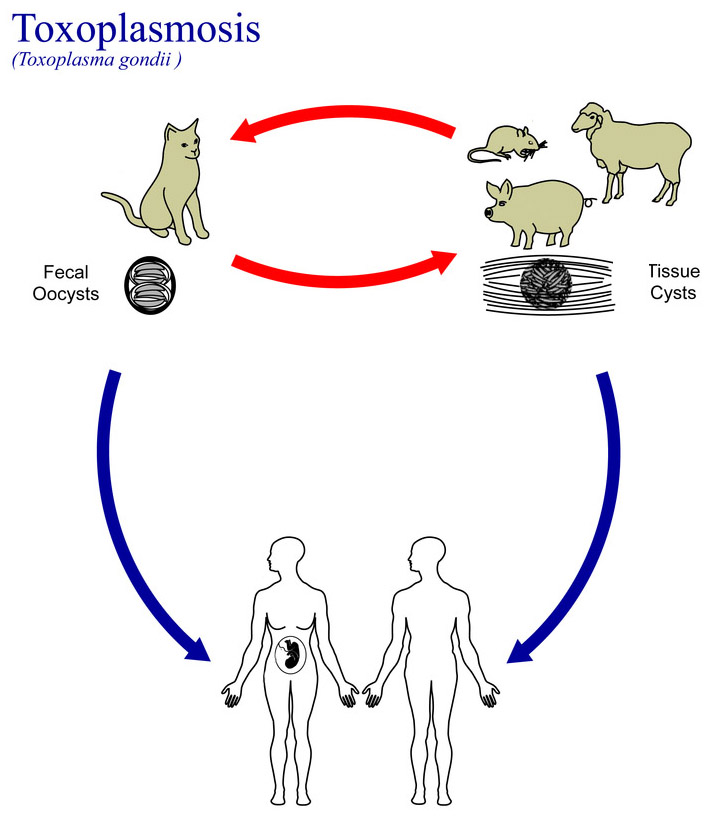

To date, there is only one known place where T. gondii can sexually reproduce: in the intestinal tract of a cat. Here, they produce millions of small, thick-walled cells called oocysts, which make their way out of the cat’s digestive system in its faeces. These oocysts can survive and remain infectious out in the world for months (possibly even years), until they are eventually ingested by another mammal or bird. Once ingested, T. gondii moves on to the next stage of its life cycle, developing into a form that can quickly spread through the body. They then form cysts in the various tissues of the body, including the brain.

This presents T. gondii with a problem: once it’s settled as a cyst in the tissues of some other animal, how can it find its way back into the gut of a cat so that it can reproduce sexually again? Well, if your new home is in the brain tissue of a rat, the answer is that you somehow convince the rat to run towards a cat, rather than bolting in the opposite direction.

Which is exactly what happens to rodents infected with T. gondii—they lose their innate fear of cats and actually become attracted to them. Instead of being repulsed by the smell of cat urine, infected rodents love the stuff. This, of course, increases the chance of infected rodents being gobbled up by a cat, allowing the life cycle of T. gondii to carry on. It’s a very smart evolutionary strategy for the parasite (and T. gondii isn’t the only living thing that can change a host’s behaviour like this—similar strategies are used by some fungi and wasps).

If you are infected with T. gondii, should you be worried? If you’re not experiencing any symptoms, the short answer is no—unless you are pregnant or have a weakened immune system. Infection during pregnancy may cause complications for the child later in life and can cause serious symptoms in immunocompromised people. Those at risk should take extra precautions to ensure meat is properly cooked and raw fruits and vegetables are thoroughly washed prior to consumption. They should also avoid changing the kitty litter where possible (or, if it’s truly unavoidable, wear gloves and wash their hands thoroughly afterwards—which is something that all cat carers should be doing, anyway).

As for whether a T. gondii infection will turn you into a crazy cat person? We don’t know for sure. While we know that infected rodents become ‘crazy cat rats’, so to speak, there’s no evidence that this specific behaviour change occurs in humans as well. So give your cat another hug. Just be mindful if you’re feeling particularly impulsive today.