What would happen if a fish went extinct on the Great Barrier Reef?

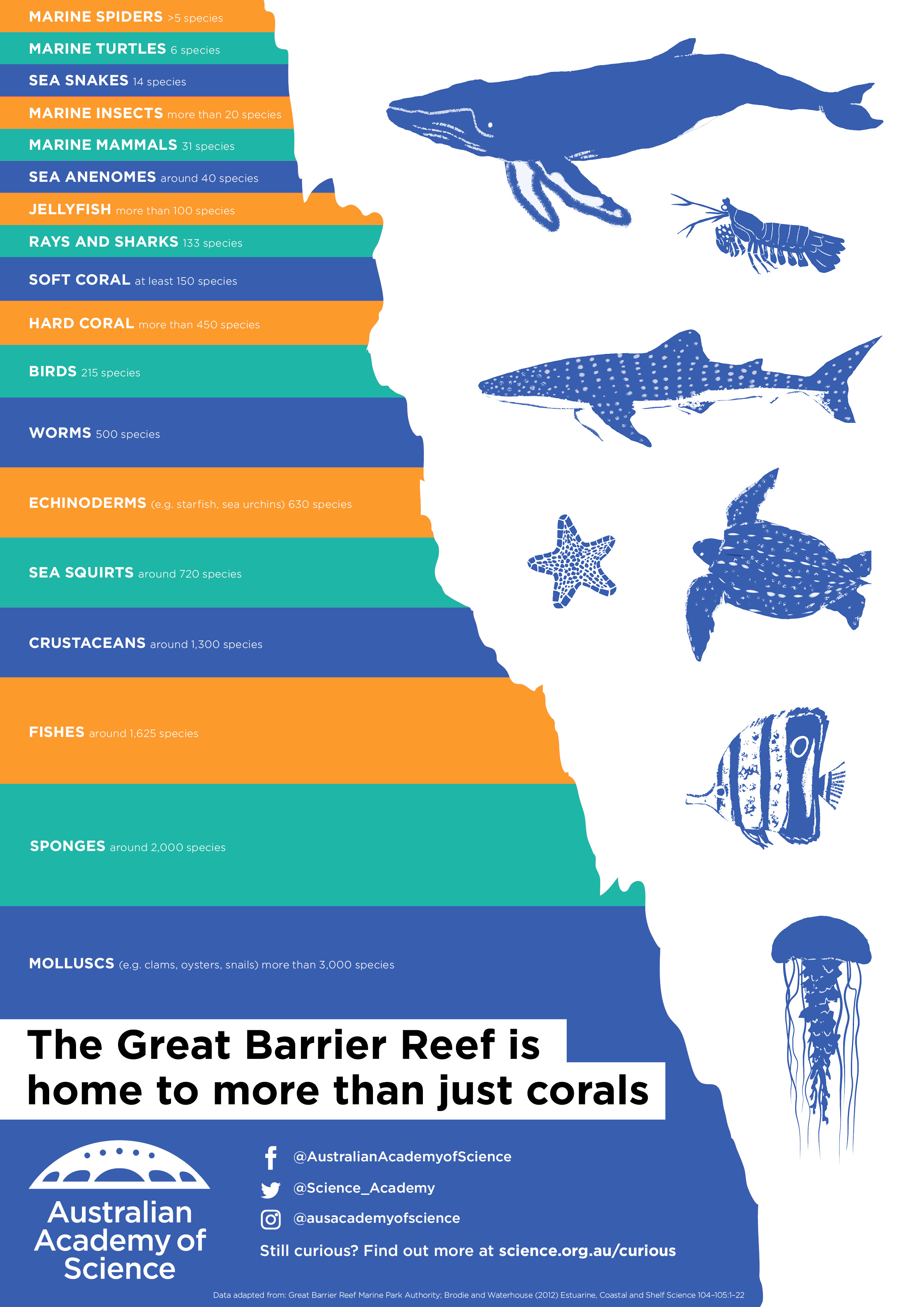

The Great Barrier Reef is a busy place. Close to 9000 species of marine life call it home—not including the huge number of microbes, plankton and fungi that also live there.

With so many different species living on the reef, it’s easy to assume that the extinction of just one or two won’t matter to the reef’s overall health. Does having so many different species benefit the reef as a whole?

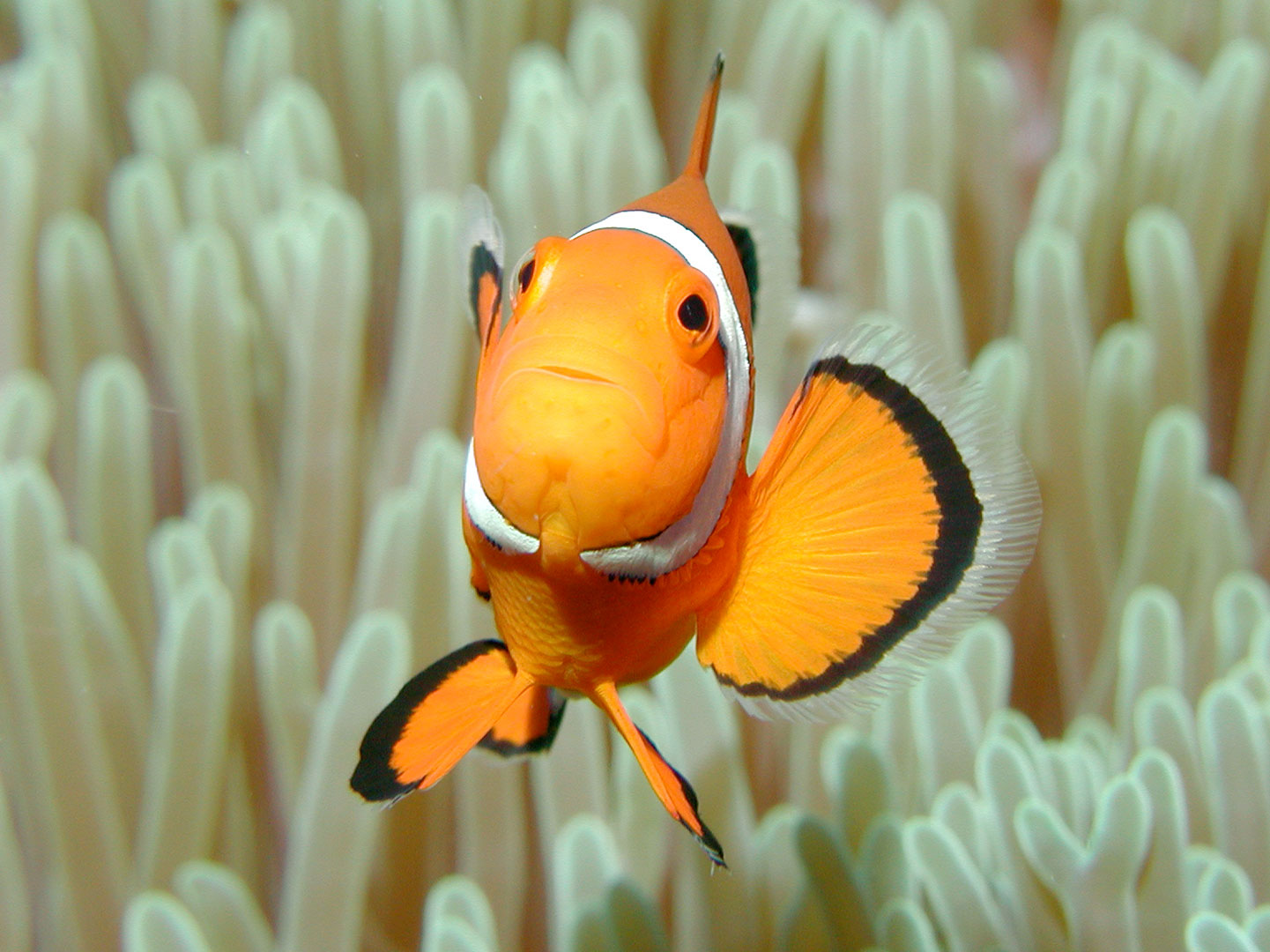

To answer this question, it’s useful to examine all the organisms and animals as if they were machines all working together in an integrated system. So, instead of looking at a fish and seeing a pretty bright orange guy called Nemo, we would look at him as a machine that performs a job. Figuring out exactly how the Nemo-machine works helps us understand what job he does, and how important both the job and machine are to the reef ecosystem as a whole. The vast suite of jobs performed by different species is known as functional diversity.

A job for everyone, and everyone doing their job

Returning to our question: maybe it’s okay if we lose one or two species, because surely another species can just take over their job?

Research done on the Great Barrier Reef says it’s a little bit of both. There is a very small subset of jobs that are extremely popular—there are lots of species all doing the same job, so yes, if one of those species disappears, the job will still get done. Eating plankton is one of these popular jobs.

Probably the most important job is providing the actual ‘bricks and mortar’ of the reef structure. The ‘bricks’ are formed by the reef-building scleractinian corals and there are various encrusting organisms (e.g. bryozoans, coralline algae, bivalves) that make up the ‘mortar’. There are hundreds of different species of scleractinian corals and lots of different encrusting organisms but the role they collectively perform is crucial. The nooks and crannies created by branches of corals is another important ‘job’—providing a safe place to live for many other species.

More alarmingly, of the numerous roles performed by reef fishes, nearly 40 per cent are performed by a single species. If these specialists disappear, there’s no one waiting in the wings to step in and do their job. High biodiversity clearly does not necessarily ensure high resilience or robustness.

Giant hump-headed parrotfish (Bolbometopon muricatum), for example, are integral to a healthy reef system. These large parrotfish eat more than five tonnes of coral reef material a year, around half of which is live corals. In a healthy system, parrotfish help remove dead coral skeletons and keep the coral growth in check, with coral growth rates roughly balancing the amount of coral eaten by the parrotfish.

Smaller parrotfish also eat a lot of macroalgae—such as seaweeds—which is important within the reef system. In over-fished or nutrient-enriched reefs, macroalgae can out-compete the corals. Without parrotfish, coral growth and reef structure can change dramatically.

Another example is the role played by the giant moray eel (Gymnothorax javanicus). The eel only eats at night. This means it preys on fish and other animals that are also active at night. These species escape being eaten by predators that operate in the daytime, and so the eel is potentially important in keeping these prey species in check.

Another specialised predator is the giant triton (Charonia tritonis). This snail is one of the very few animals that can eat the extremely voracious, coral-eating crown-of-thorns starfish (Acanthaster solaris). Although they generally eat only one starfish a week, their very presence helps to disperse groups of crown-of-thorns starfish, weakening their ability to breed and multiply on the reef.

The surgeonfish is another important reef-dweller. Like many parrotfish, it is essential in the process of sediment removal. A study of surgeonfish (Ctenochaetus striatus) on the Lizard Island reef, in the northern Great Barrier Reef, found these fish ate between 8 and 66 grams of sediment per day. They generally get rid of their stomach contents in a different location to their eating grounds and around one third of the sediment they eat is deposited off the reef in deep water. This process helps maintain the reef and possibly specific algal habitats, which are a valuable food source for herbivore fishes.

Whether looking at the sheer numbers of species of marine life or the range of tasks and jobs they carry out on the Great Barrier Reef, it’s clear that the reef is an amazingly intricate and dynamic system. It’s also fragile. The specialised nature of many of the jobs carried out by the different species on the reef mean that we cannot take the reef’s resilience for granted.