What did Neanderthals eat?

Neanderthals didn’t have toothbrushes. This may seem like an obvious fact, but it’s a stroke of luck for today’s scientists. The lack of prehistoric dental hygiene resulted in teeth gunk that would shock your dentist—but that also contains a goldmine of information.

Straight from the Neanderthal’s mouth

If you don’t wield a toothbrush regularly, a thin sticky film made from proteins and microbes forms on the surface of your chompers. This is called dental plaque. Over time, plaque hardens to form tartar or dental calculus (the technical names for tooth crust). Calculus is a combination of different calcium phosphate minerals—the same stuff our actual teeth are made from—sometimes with small amounts of magnesium or iron incorporated into their crystal structure. As these minerals form, tiny bits of microbial and food matter can be trapped inside. Encased in the hard, mineral crust, this matter can be preserved for thousands or even millions of years.

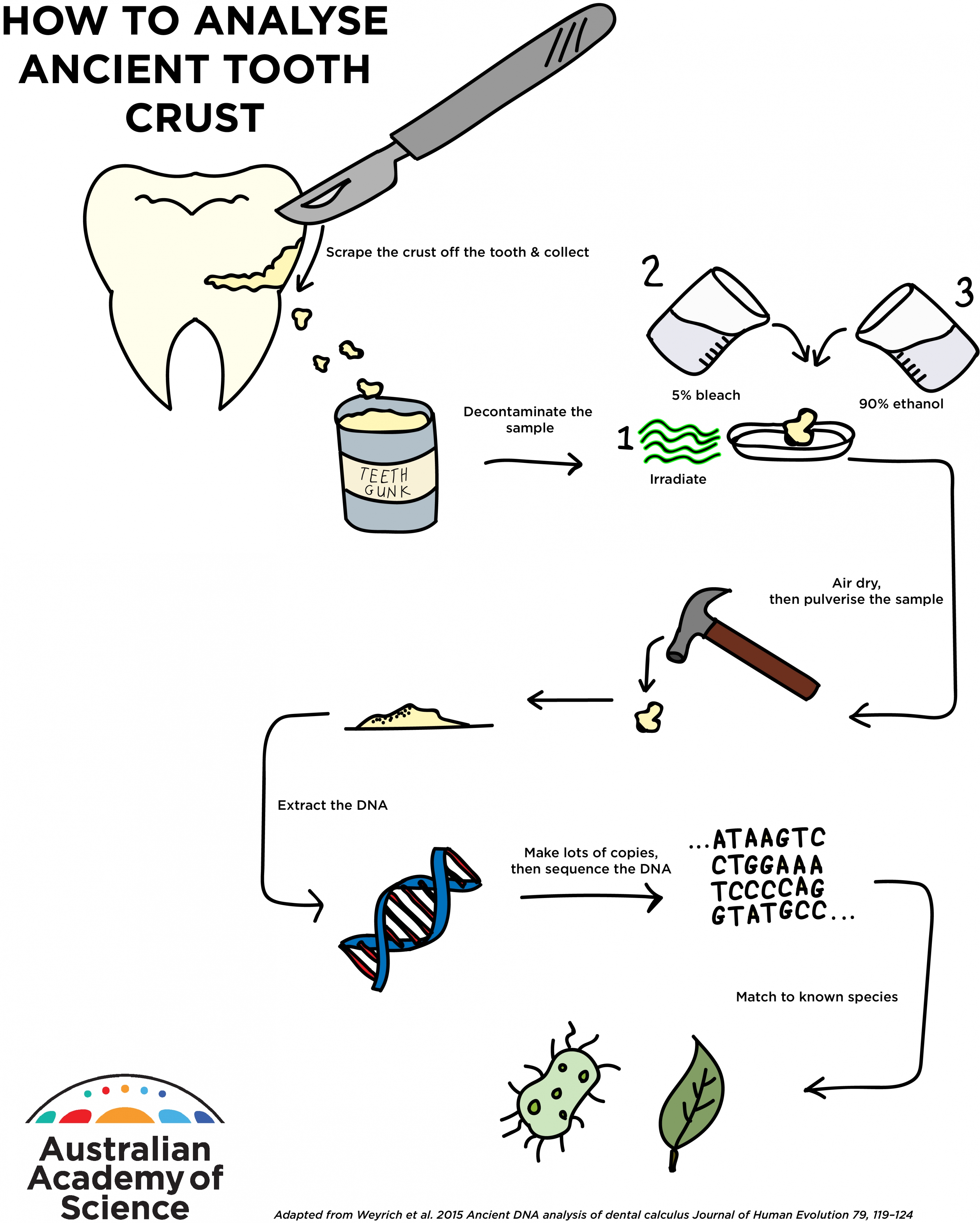

Fast forward to the present, and modern scientists can examine the ‘bits’ hidden in fossil teeth gunk. They can determine the species of microbes present in the mouth of a Neanderthal—our closest known hominin relative—by extracting ancient DNA. Or, they can investigate tiny lumps of protein, starch and plant matter to figure out what our ancestors ate and what their lifestyles were like.

A Neanderthal’s favourite food

DNA present in Neanderthal dental calculus from samples found in the Spy cave in Belgium suggests that these chaps were meat-lovers, dining on woolly rhinoceros and wild sheep.

Further south, two Neanderthals unearthed in the El Sidrón cave in Spain carried evidence of a more plant-based diet: mainly mushrooms, pine nuts, moss and even tree bark. Another study found a variety of plant microremains in teeth gunk from specimens that lived in different environments, dispelling the stereotype of Neanderthals as solely meat-eaters.

The Spanish Neanderthals also offered a glimpse into health issues 49,000 years ago. One suffered from a dental abscess, which was evident in his skeletal material. In this individual’s dental calculus, the researchers found the DNA of Enterocytozoon bieneusi, which is a rather unpleasant gastro parasite.

In the same sample, scientists detected the DNA of poplar bark. Poplar bark contains salicylic acid—the basic ingredient of aspirin. Also found were traces of the Penicillium mould, which likely came from eating mouldy plant material. These ‘medicinal’ items led to the conjecture that this individual was attempting to treat his health issues with pain-killers and antibiotic products.

Decoding ancient microbiomes

Bacteria can also be encased in teeth gunk. Everyone has a slightly different complement of bacterial hitchhikers, which collectively form the ‘microbiome’. It is possible to find entire ancient bacterial organisms preserved within dental calculus. Scanning electron microscope images show many different types of bacteria, but identification of the full suite of microbes present requires DNA extraction and sequencing.

Like their diets, the microbiomes of Neanderthals varied widely. Interestingly, Neanderthals possessed a species (Methanobrevibacter oralis) that is also found in the mouths of modern humans. This suggests that Homo sapiens and Neanderthals swapped saliva—perhaps via sharing food, kissing or perhaps passed down from a common human/Neanderthal ancestor. Researchers sequenced the genome of this ancient microbe species and found several key genetic differences compared to modern variants. The ancient version lacked genes for antiseptic resistance and digesting certain sugars, suggesting that the species has adapted to changes in hygiene and diet.

More contemporary calculus from modern humans around 1000 years ago contained evidence of familiar oral pathogens, gastrointestinal bugs and the sexually-transmitted disease gonorrhoea.

Crusty teeth aren’t all bad

Beyond the diet and microbiome information encased in tartar, other studies have chipped away to discover cotton fibres, human DNA and animal milk proteins—which hint at craft activities, ancestry and milk consumption respectively. Dental calculus is also widespread in the fossil record. It’s been found on two million-year-old Australopithecine fossils (a distant human ancestor) and 12 million-year-old fossils of an orangutan ancestor. With its prevalence, scientists are just starting to scratch the surface of dental calculus and all the information it contains.