Don't catch my disease

29 July 2020

Ebola. COVID-19. Avian influenza. SARS. Zika virus. What do these infectious diseases all have in common?

They all originated in animals before they infected humans.

They’re not the only ones either. In fact, around 60 per cent of infectious diseases in people are zoonotic.

‘Zoonotic’ is simply the term that describes a disease that can be spread between other vertebrate animals and humans. The actual nature of zoonotic diseases (also known as zoonoses) can differ quite a bit: they may be caused by viruses, parasites, bacteria or fungi.

The number of new zoonotic diseases affecting us is on the rise and our globalised world makes us even more vulnerable to their impact. Anecdotally, you might feel this stacks up. We all heard or even experienced how COVID-19 began to infect humans in late 2019. The first cases are likely to have originated from animal sources before spreading globally and affecting many millions of people directly and billions indirectly. COVID-19 is the very definition of a pandemic.

How does disease spread between species?

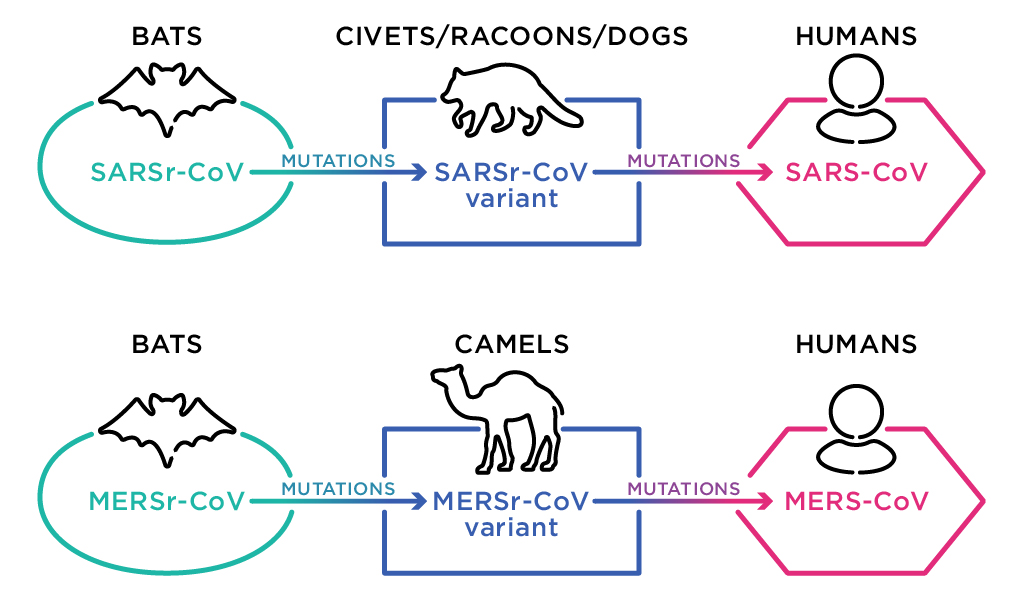

When a disease crosses from one species in to a new species, it is known as spillover. Like liquid can spill from a cup, a disease can ‘spill’ from one species to another. While disease spillover sometimes seems rapid—one day it existed only in bats, the next it appears in humans—the process is usually a long evolutionary change. A virus, for example, may mutate gradually until the genetic information in the virus changes enough to enable the virus to survive and replicate in another species. Spillover can only occur when a certain mutation that allows that virus to infect another animal species is made. The other species may be humans, or another intermediary animal species. Once this new mutated version of the virus exists, and provided that a series of other factors align, the disease may then spread throughout the new species. If the disease spills over from an animal to humans, then it is known as zoonotic disease spillover.

Zoonotic diseases, whether they are viruses or caused by something else such as bacteria or parasites, usually spill over at places where animals and humans are in close contact. For example, it is suspected that Ebola was transmitted from primates to humans through the hunting and eating of bushmeat. MERS (Middle Eastern respiratory syndrome) originated in dromedary camels, and the SARS outbreak in 2002 was linked to international trade of small carnivores, including palm civets, raccoon dogs and ferret badgers. In the US in 2003, the act of people keeping prairie dogs as pets caused an outbreak of monkeypox.

Scientists have found that bats, primates, rodents and resilient, abundant wild mammalian species are often involved in spillover. Conversely, threatened wildlife species, particularly those with decreasing populations because of exploitation and loss of habitat, also share more viruses with humans.

While the spillover of the virus causing COVID-19 likely took place in Wuhan, the finer details, such as which animal species it originated in are still a little murky. A virus that is genetically 96 per cent similar to SARS-CoV-2 (the virus causing the COVID-19 disease) has been found in bats, so bats are likely to be involved somewhere along the chain. But scientists say that there is probably an intermediary species involved in the transmission. The middle animal in the puzzle may be the humble Malayan pangolin. This idea is part of a changing body of evidence at the time of writing (mid-2020), so there is no certainty and it needs much more evidence.

What about farm animals and pets?

Wild animals cop a lot of the heat, but domestic and farm animals are not off the hook as disease hosts and transmitters. The closely-packed environments that many farm animals are increasingly found in may allow diseases to spread rapidly. And the animal products we eat have the potential to spread diseases widely. The main difference here is that in domestic situations, animals are usually more closely monitored, and given veterinary care and disease-prevention measures such as vaccination.

When handling domestic animals, farmers and pet owners also need to be aware of keeping good hygiene, such as washing hands afterwards to reduce disease spread. It’s also important to be careful to avoid contact with animals when we are sick—as disease can spill both ways.

Is it inevitable, or can these diseases be prevented?

Our globalised society increases the likelihood of zoonotic disease spilling over to humans, and with every spillover comes the increased risk of future epidemics and pandemics. Climate change (pdf) alters ecosystems and changes the geographical range of some disease vectors like mosquitoes. Our global trade and travel has people, animals and animal products moving further and faster than ever. Additionally, as the world’s population increases and we change or destroy wildlife habitats, people are either living closer to wildlife or in more densely-packed areas. There is also an increased demand in food supply that has resulted in more intensive agricultural animal production. Despite all these factors that increase risks of spillover and spread of infection, there are ways that we can reduce the transmission of disease.

On the COVID-19 crisis, virologist and Fellow of the Australian Academy of Science, Professor Eddie Holmes, says “Wildlife contains many coronaviruses that could potentially emerge in humans in the future. A crucial lesson from this pandemic to help prevent the next one is that humans must reduce their exposure to wildlife.” This may be by reducing the sale of wild mammals and birds at food markets, reducing illegal wildlife trade, and letting wild animals remain wild. More research and surveillance of animal diseases will also help scientists predict and then try to prevent other emerging diseases. Alongside this, the community needs to be educated about zoonotic disease and hygiene practices with food products and animals.

We need to change our behaviours, living circumstances and actions. To do this, cultural, political and economic factors come into play, as well as the science. For example, people may continue hunting bushmeat, despite theoretically knowing the risks for disease such as Ebola, but with little choice due to poverty and limited access to other food. These underlying issues and motivations for our behaviour need to be addressed in order to fix the root problems of humans interacting closely with wildlife in risky ways.

To solve these problems and mitigate risk factors for zoonotic diseases it takes collaboration between organisations, decision-makers and experts of multiple disciplines, and including local communities. It’s not an easy task, but by working together, nations can help prevent animal–human disease spread and emerging infectious diseases wreaking havoc to our world in the future.