What we know about the AstraZeneca vaccine and blood clots

7 May 2021

The AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine has made headlines across the world for its potential links to a very rare, but serious, syndrome involving blood clotting and low platelet levels. Many people are understandably concerned: What's causing these blood clots in the first place? How are they different to other types of blood clots? And why wasn’t this picked up during the vaccine’s clinical trials?

Here is what we know so far about the science behind blood clotting, our understanding of how it might be connected to the AstraZeneca vaccine, and how scientists and health authorities are investigating the risks.

What is blood clotting?

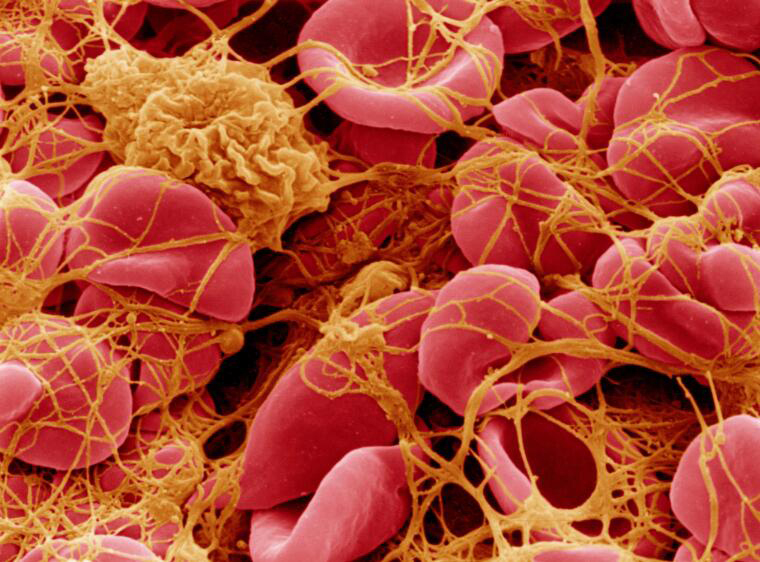

Blood clotting is a process your body uses to prevent bleeding. When a blood vessel is damaged—for example, if you cut yourself—blood cells called platelets rush to the site of the injury and clump together with proteins and other blood cells, forming a clot to plug the hole. This minimises further bleeding while your body starts repairing the damage.

However, sometimes a clot can form inside a vein or artery. This blocks the normal flow of blood in that part of the body and can cause serious harm, especially if it restricts blood flow to tissues or vital organs like the brain (such as in the case of stroke). There are lots of different reasons why problematic clotting might occur—some common causes include recent surgery and reduced mobility, genetic disorders that make blood more prone to clotting, or medications that affect certain hormones, such as the oral contraceptive pill. Even sitting still for a long time, like on a long international flight, can lead to clotting in the deep veins of the legs.

Blood clotting is a complex process, involving many different proteins and chemical messengers all interacting with each other in a series of reactions. Venous thromboembolism, an umbrella term for several common blood clotting diseases, is quite common, affecting roughly 17,000 Australians each year. While cases can vary in severity, many are treatable with medications such as heparin and other anti-clotting treatments.

Blood clots are a known complication of COVID-19 itself. One analysis found that 14.7 per cent of COVID-19 patients developed some form of blood clotting, often in places like the legs or lungs, where other blood clots are more commonly found.

What is ‘thrombosis with thrombocytopenia syndrome’ (TTS)?

Health authorities have noticed a rare pattern of symptoms that some people have experienced following an AstraZeneca vaccination. This collection of symptoms has been called ‘thrombosis with thrombocytopenia syndrome’, or TTS, and involves the formation of a blood clot (also called thrombosis), typically in uncommon places such as veins in the brain or abdomen, together with low levels of platelets in the blood (also called thrombocytopenia).

Although TTS is serious, it’s also very rare. The Australian Technical Advisory Group on Immunisation (ATAGI) estimates that out of every 100,000 people vaccinated with AstraZeneca, one or two people may experience TTS. The risk might be higher for people under 60, but any estimates of risks for specific age groups are still imprecise because there are so few cases to analyse.

The syndrome is similar to another rare condition called heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, which occurs when someone has an unusual immune reaction to heparin, a common anti-clotting medication. In these cases, heparin interacts with a protein found in blood platelets called platelet factor 4 (PF4). The immune system then mistakenly interprets this PF4-heparin combination as foreign and produces antibodies to attack it. This triggers a chain of events where platelets become ‘activated’, sticking together to form clots. The immune system keeps activating platelets, leading them to release proteins into the bloodstream that stimulate the clotting system to produce even more clots.

Scientists think a similar reaction might be taking place caused by the AstraZeneca vaccine (or components of it) interacting with PF4 proteins and triggering an immune response. It is particularly challenging for scientists to study the way TTS works, because it is so rare.

It is important to realise that most blood clots are not caused by immune processes. This suggests that, for people who have experienced blood clots in the past, or have other risk factors that might increase their chances of developing a clot (such as taking the oral contraceptive pill), the AstraZeneca vaccine may not pose an extra risk, because the causes of the clotting are fundamentally different. Scientists and health authorities have not yet been able to confirm how AstraZeneca vaccine causes blood clots—there is still a lot that we simply don’t know.

However, we do know that even if someone becomes ill with TTS, doctors now have a better understanding of the condition. It’s much easier to diagnose and get the right treatment, so the chances of recovery are higher than they were before.

How are scientists and health authorities investigating the link?

Health authorities have seen enough cases of TTS taking place from 4 to 30 days following an AstraZeneca vaccine to say a link between the vaccine and the disease is likely.

The first signs of a possible link between the AstraZeneca vaccine and unusual blood clots appeared as vaccination programs were rolled out in several European countries. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) identified a pattern in their data (statisticians call this a ‘signal’) about unwanted health impacts following vaccination. The signal showed that a small number of people were developing serious and unusual blood clots in combination with low levels of platelets within a month of receiving the AstraZeneca vaccine. Countries like Germany, Norway and Spain made the decision to temporarily pause their vaccine rollouts so health authorities could investigate the problem before restarting the program.

A signal can only indicate that there may be a link between a vaccine and a side effect: it raises a flag for health authorities to show that further investigation might be needed. It cannot provide any information about why the side effect might occur, or whether some groups of people are at higher risk than others. A signal doesn’t always mean the vaccine directly causes that side effect. Answering these questions requires further investigation into what’s causing the problem and how it might (or might not be) linked to a vaccine, as has been done with the AstraZeneca vaccine and TTS.

The rarity of TTS is the main reason it was not detected during vaccine clinical trials. Clinical trials typically involve many thousands of people, not millions: if a side effect or complication only occurs for a few people out of a million, it may not happen for any of the participants in a clinical trial. This is why health authorities continue to monitor a vaccine’s safety as it is rolled out more widely so that very rare potential side effects can be identified and investigated.

Importantly, the overall number of reports of blood clots following vaccination is not a cause for concern. There will always be a chance that someone will develop a blood clot regardless of whether they’ve just received a vaccine or not—health authorities refer to this as the ‘background rate’ of a given symptom or disease. These more common cases of venous thromboembolism, which are not associated with low platelet levels, do not meet the criteria for TTS and are unlikely to be caused by the vaccine.

Even with the small risk of TTS associated with the AstraZeneca vaccine, it is still highly effective at preventing severe COVID-19. Health authorities must balance the risk associated with the vaccine against the significant benefits of vaccination in protecting individuals and the community against severe illness and death from COVID-19. All COVID-19 vaccines currently in use are valuable tools for controlling the spread of disease and limiting the serious complications that COVID-19 can cause.