What's happening to Australia's rainfall?

- Extreme rainfall and droughts are deeply ingrained in Australia’s climate history.

- A major driver for rainfall variability in Australia is the El Niño–Southern Oscillation, which impacts the crop growing season in eastern and northern Australia.

- Australia’s geographical location makes us vulnerable to the climate system created by the Pacific, Indian and Southern oceans.

- Long-term drying and changes to rainfall patterns have impacted our water supply and Australians are having to find alternative sources.

- Australian agriculture is resilient and has adapted to make the most of the good years.

- Understanding how climate change will impact Australia’s rainfall patterns into the future will help us make key decisions in sustainable water management and agriculture.

Australia is a land of “drought and flooding rains”. As rainfall varies significantly from year to year and from decade to decade, recurring floods and droughts are deeply ingrained into our culture. More recently, we’ve seen longer-term changes in some parts of the country.

Australia has a history of variable rainfall patterns

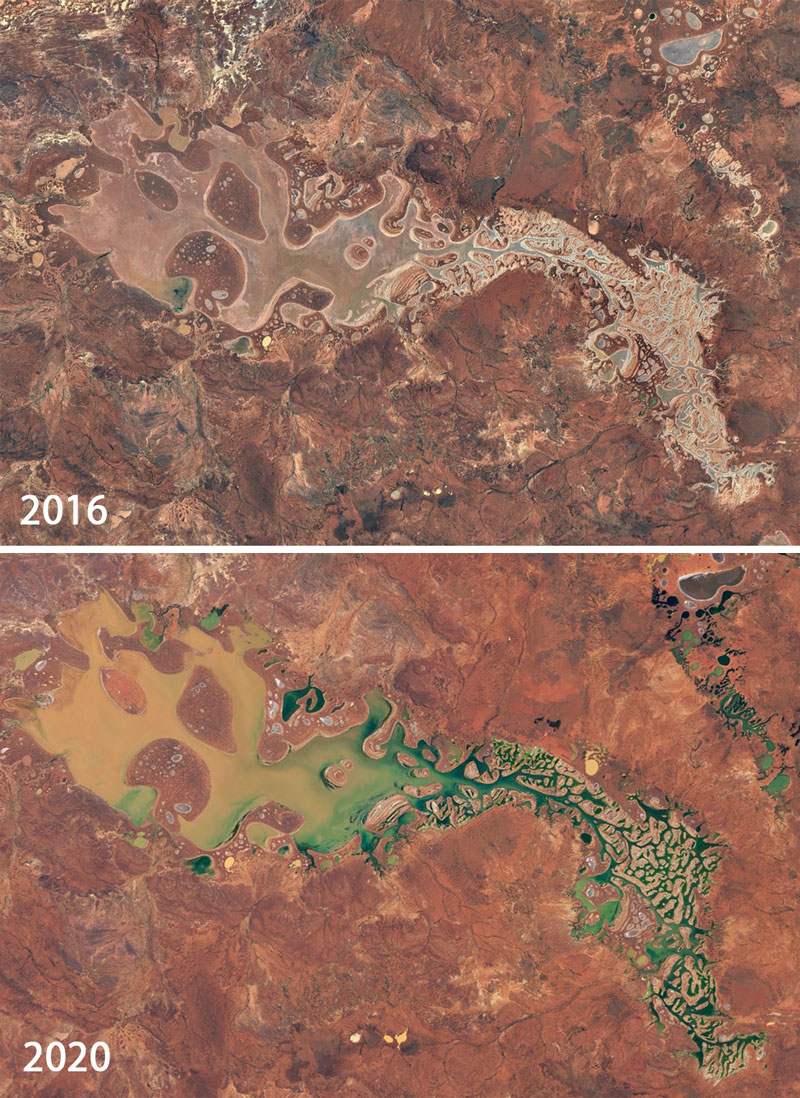

Compared to many other parts of the world, Australia’s rainfall varies a great deal from year to year. In the worst drought years, such as 1902 and 2019, some places had annual rainfall less than one-fifth of the long-term average. Conversely, even the driest parts of Australia occasionally get extremely heavy rainfall, often following tropical cyclones or monsoon depressions. Lake Carnegie, in central Western Australia, only fills following periods of significant rainfall. The Lake Carnegie region averages 235 mm of rain a year but received 270 mm in a single day in early 2020, which filled up the lake.

Lake Carnegie in Western Australia is an ephemeral lake and only fills with water following significant rainfall. In early 2020, an unusually wet season resulted in significant amounts of rain across Lake Carnegie. The above images show the lake in 2016, and in March 2020 following the rainfall. Source: 2016: Google Earth, imagery date 31 Dec 2016; Image Landsat/Copernicus 2020

The east coast of Australia is also prone to extreme rainfall. Many locations on the New South Wales and Queensland coasts, including Sydney and Brisbane, have had more than 300 mm in a day at least once in their history, and at some coastal mountain sites, daily totals over 600 mm have occurred. These rainfalls can produce destructive flooding in rivers along the east coast, such as those which affected Brisbane and surrounding areas in January 2011.

There can be enormous variation in rainfall from one decade to the next. The drier parts of Australia’s interior are especially variable. Marree, in the South Australian outback, averaged only 110 mm a year in the 1960s, but more than double that, 247 mm a year, in the 1970s. Averaged over the state, South Australia had 17 years in a row of below-average rainfall from 1922 to 1938, highlighting how dry phases can last for long periods of time. Some of the driest decades are part of our history, such as the Federation Drought of 1895 to 1902 and the more recent Millennium Drought of 1996 to 2010. In the earlier years of European settlement, wet periods such as the 1870s and early 1890s encouraged farmers to move into new areas, only to fail as drier conditions returned. Even the east coast can have large rainfall swings; Sydney’s average rainfall in the 1950s was more than 40 per cent higher that of the 1900s or 2000s.

Drivers of rainfall variability from year to year

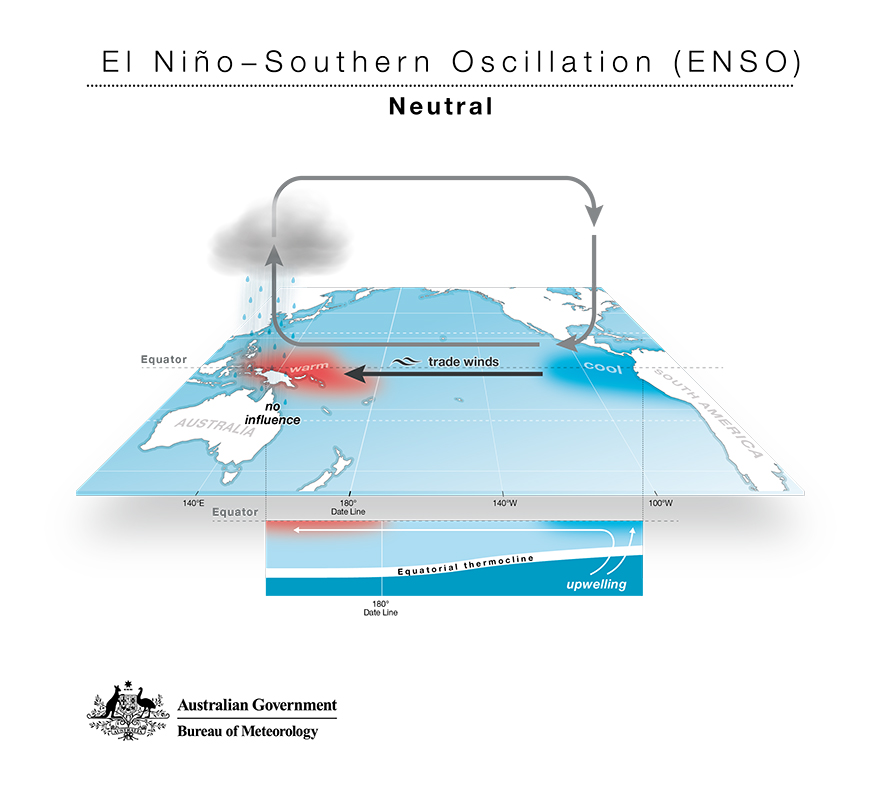

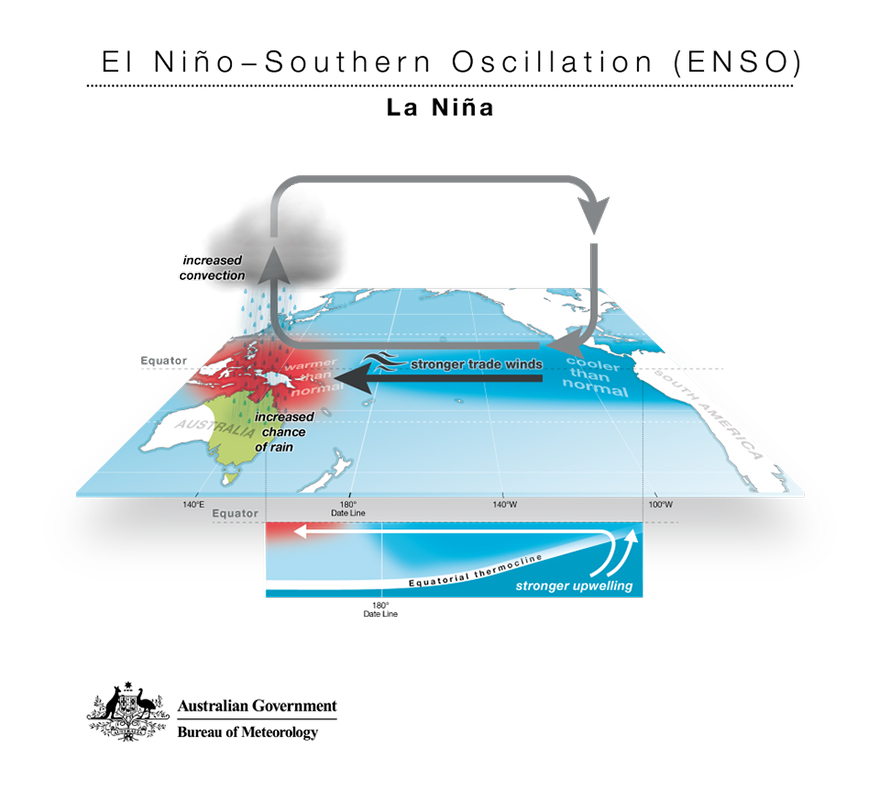

A major driver for rainfall variability in Australia is the El Niño–Southern Oscillation, a phenomenon centred in the tropical Pacific Ocean. During an El Niño year, the waters of the equatorial eastern and central Pacific warm above their usual levels, easterly winds in the tropics weaken, and drought often affects eastern and northern Australia, especially in winter and spring. This is the main growing season for Australia’s winter crops such as wheat and barley, and the main filling season for south-east Australia’s major water storages.

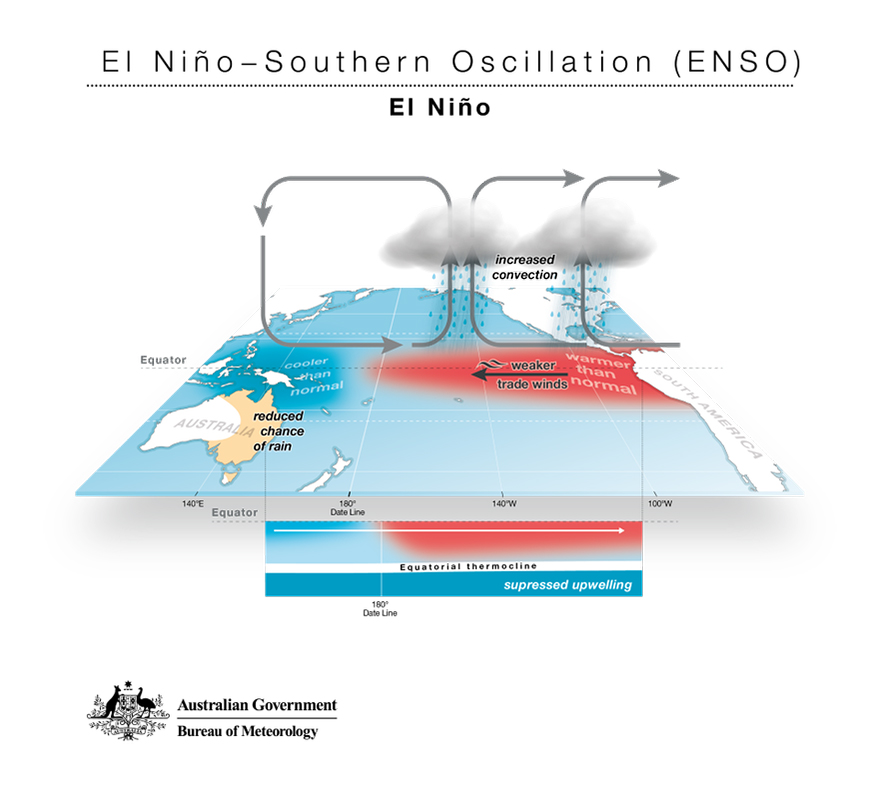

Conversely, a La Niña occurs when the tropical eastern and central Pacific Ocean are unusually cool, a pattern which often brings heavy rain to many parts of Australia. More recently, the role of the Indian Ocean north-west of Australia as a moisture source has also become apparent, with drought common in years when it cools, such as 2019, and heavy rain in years when it is unusually warm, such as 2016. This driver is known as the Indian Ocean Dipole. While the tropical Pacific and Indian oceans influence the climate system in many parts of the world, Australia is among the more vulnerable countries given our proximity. There is also growing evidence that climate change is altering the way that natural variability operates in the oceans, particularly the Indian Ocean, which has the potential to increase the chance of Australia experiencing wet and dry extremes.

El Niño and La Niña are weather patterns that result from increasing and decreasing water temperatures in the Pacific Ocean. For Australia, El Niño events typically mean lower rainfalls and higher temperatures whilst La Niña events typically mean higher rainfalls and lower temperatures. Images adapted from: Australian Bureau of Meteorology.

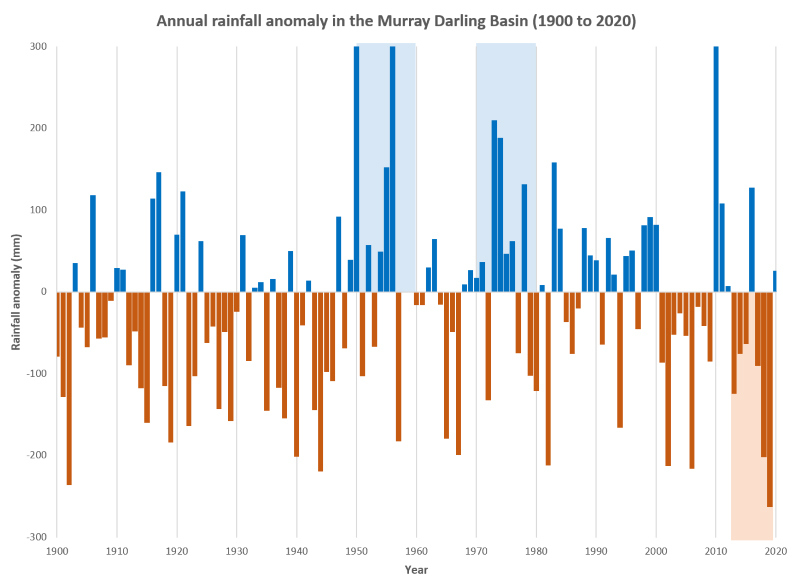

These climate drivers influence our rainfall over longer timescales too. While individual El Niño events or abnormal Indian Ocean conditions rarely last for more than a year, a cluster of events in rapid succession can drive anomalies over much longer periods. Eastern Australia’s wettest decades, such as the 1950s and 1970s, occurred when there were several La Niña events within the space of 10 years or so.

Longer-term changes in rainfall patterns and the impact on Australians

Longer-term changes in Australian rainfall have become increasingly important for informing how we can sustainably use and manage the land. The most obvious change we have seen in Australia is the decline in rainfall in south-western Australia since the 1970s, as the subtropical high-pressure belt has expanded and the westerly winds that bring the region much of its winter rain have moved south. Annual rainfall in south-western Australia has decreased by 10 to 20 per cent. This has had a profound impact on Perth’s water supply, which has become increasingly reliant on groundwater and desalination. Inflows into dams have become unreliable, dropping almost to zero in the driest years such as 2010.

Rainfall trends over Australia from 1960 to 2020, showing the drying in south-western and south-eastern Australia and wetter conditions in the northwest. Image adapted from: Australian Bureau of Meteorology .

Since the 1990s, long-term drying has also emerged in parts of south-eastern Australia, especially in Victoria. This drying is concentrated in the cool season between April and October, with little change in summer rainfall, and has placed significant stress on agriculture and water resources in the region—inflows into the Murray River from 1997 to 2009 were 40 per cent below the long-term average. The fundamental driver of the change is similar to that experienced in the south-west of the country. We see this in many other parts of the world at the same latitude, and it’s consistent with changes we would expect to see with increased levels of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere.

In contrast to the south-western and south-eastern parts of Australia, many parts of tropical Australia have seen increasing rainfall in recent decades. Rainfall has increased by 20 per cent or more since the 1960s in many parts of north-western Australia, such as the Kimberley in Western Australia, and the Northern Territory Top End, and increases in rainfall have also extended south into much of the western interior. These increases, related to changes in the behaviour of the summer monsoon, are not as yet well understood as the declines in the south and it is unclear if these changes represent a long-term trend or an extreme phase of naturally-driven variability. The 2018−19 and 2019−20 summers were both unusually dry in north-west Australia, but it remains to be seen whether this is a temporary fluctuation or marks a return to the rainfall regimes more typical of the 1960s and earlier.

Eastern Australia is another region where the longer-term picture is complex. In inland New South Wales and southern Queensland, taking in most of the Murray–Darling Basin, the 2017–19 drought was of unprecedented intensity. In 2019, some parts of inland north-east New South Wales and the Darling Downs received rainfall totals which were more than 50 per cent lower than previous record lows. However, the broader rainfall patterns of the last 30 years have been comparable to those of the first half of the 20th century, with a wet period between about 1950 and 1990. While annual rainfalls have fluctuated, there has been a shift in rainfall seasons since the 1990s, with a higher proportion of annual rainfall in the warmer months and less in the cooler months. Although this seasonal shift is consistent with the longer-term changes we would expect with climate change, our agricultural crops grow in the cooler months and summer rainfall is often less reliable than winter rainfall and is more affected by evaporation. These changes may impact our agriculture practices.

Annual rainfall anomalies averaged over the Murray-Darling basin. The wet decades of the 1950s and 1970s and the extreme drought of 2017 to 2019 are highlighted. Image adapted from: Australian Bureau of Meteorology.

Rainfall extremes and life as we know it

One of the big uncertainties about Australian rainfall is what happens at the extremes of rainfall pattern changes. Extreme high rainfall can cause destructive floods, whether that is localised flash flooding from severe thunderstorms, or more large-scale and widespread river flooding from extensive rain events.

The Brisbane and Sydney water supply catchments get much of their inflow from extreme rain events, so a prolonged lack of extreme rain events—as happened between 1998 and 2007 in the Sydney catchment—can place considerable stress on water supplies. We expect to see more intense rainfall extremes in a warmer world. More intense rainfall extremes are visible in many regions, especially the mid-latitude continents of the Northern Hemisphere. There is not yet clear evidence of increased rainfall extremes in most of Australia: separating long-term changes from normal fluctuations in Australia’s variable climate is difficult for annual rainfall, but even harder for extreme events. However, as global warming continues, it is likely that intense short duration rainfall events (daily and shorter timescales) will increase, even in those regions that are likely to see an overall rainfall decline such as much of southern Australia. As flooding is driven by extreme rainfall events, this means that we may see more floods—even in a drier climate overall—and need to plan for them.

Highly variable rainfall is something Australians have lived with and adapted to since the earliest days of human settlement. Many forms of Australian agriculture are adapted to making the most of the good years, and Australia has numerous water storages that are large enough to hold enough water to withstand years of drought. Some have also used Australia’s large land area as a means of diversifying their risk; for example, the Kidman family cattle-grazing operation had properties over a region extending from the Kimberley to Queensland’s Channel Country and the Flinders Ranges of South Australia, as drought rarely affects all areas of the outback at the same time.

Climate change already influences how water is managed in Australia and how agriculture is practised. A better understanding of how Australia’s climate will look in the future will help us make key decisions in those areas. Even without longer-term changes, the drought of 2017−19, and the floods of the early 2010s, are stark reminders of just what rainfall extremes are possible in Australia, and of what Australia must be able to manage.

This topic’s links to the Sustainable Development Goals:

This article has been peer reviewed by the following experts:

Professor Nerilie Abram, ARC Future Fellow, College of Science, Australian National University, Dr Andrew King, Lecturer in Climate Science and ARC DECRA Fellow, School of Earth Sciences and ARC Centre of Excellence for Climate Extremes, University of Melbourne.