Is it legit? Top tips for spotting misinformation

28 June 2022

You’ve probably heard this advice when searching for information about health or science on the internet: ‘Find a reliable source’. But deciding what is reliable is easier said than done in our oversaturated online world. Here are some tips for deciding what and who to trust when you’re looking for scientific information.

Imagine you’ve seen a post about COVID-19 vaccines from a friend on social media – do you immediately trust that information? Where do you go to check that it is based on relevant facts?

It is human nature to trust something shared by someone we know and like, but even if a person is trustworthy it doesn’t mean the original source of the information is accurate. Everyone has biases (which may be subconscious or gut feelings), and we tend to seek out and pay attention to things that match our views of the world. This is partly why misinformation travels quickly.

When the topic has the potential to cause harm we need to be even more careful about the strength of evidence. This is known as the precautionary principle – meaning if there’s a possibility of big consequences, we should err on the side of caution. This is often the case for health and medical topics. For example, if you saw a tweet that said it was safe to jump off a cliff, you would very much want to find evidence elsewhere before doing so. And if the conclusion isn't clear – err on the side of enjoying the view instead.

We need to channel our inner detectives and decide whether the information we consume and share really is reliable. At the least, actively asking ‘is this misinformation?’ is an important first step.

Who should we trust?

So, who should we trust online? For health and medical information, as the first port of call, go to websites from your national, state or local governments or from official (government-funded or endorsed) organisations. A good trick to know a website is official is to look at the end of the web address for .gov (government institution) .edu (educational institution) or .org (registered organisation). On the other hand, if it ends in .net or .com, it’s not necessarily very trustworthy as almost anybody can set up these websites. Medical information often goes out of date quickly (especially in a pandemic), so always check when it was last updated and choose the most recent official source. It is ideal if it comes from your own country or jurisdiction.

Government websites give you practical details such as which vaccine you may be eligible for or the steps you should take if you feel unwell with COVID-19. However, if you are looking for the answer to a specific scientific question, you may need to look elsewhere.

Often organisations such as hospitals, universities, not-for-profit organisations, news outlets and independent science communication publishers produce fact sheets, blogs and other easy-to-understand guides to scientific and medical information. These can be good, trusted points of information that bring together and explain complex scientific information, but it is still important to consider the expertise and motivations of all publishers. It is a matter of weighing up the clues you find that suggest a source may be reliable or unreliable.

Reliable online sources for COVID-19 vaccine information in Australia include:

- Australian Government webpages

- your local or state government webpages

- MyAus COVID-19 app by the Migration Council for resources in multiple languages

- medical institutes and learned academies like us, the Australian Academy of Science

- the World Health Organization

- RMIT/ABC FactCheck

Question whether this organisation or individual has anything obvious to gain from what they are telling you. They could be promoting certain ideas or values, or advertising a product or service. Typically, if they are trying to sell you something, they are less likely to be reliable as a scientific source. To find out if the publisher has a good reputation, you could use a search engine to find out what other people are saying about them, but of course consider the opinions of others with some caution too.

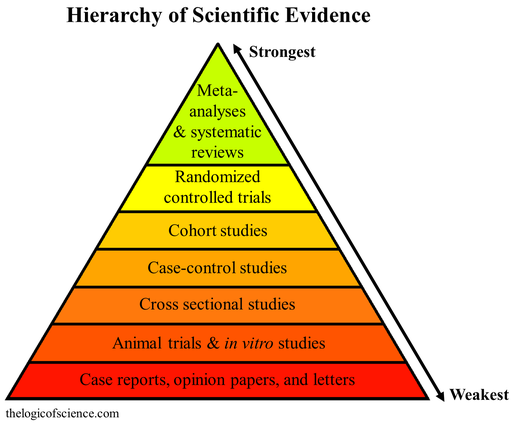

Also take a look at the sources that they refer to, if any. If they base their content on peer-reviewed science (published in an academic journal) or official government information, or quote relevant experts with a good reputation, then they are more likely a good source. If the only ‘evidence’ provided is an anecdote, case study or story, this is not reliable on its own. One story doesn’t tell the bigger picture. If they quote someone who is not an expert on the topic, or has expertise in a different area, that is not reliable either. For example, a professor in quantum physics does not necessarily have the expertise to explain the intricacies of COVID-19 vaccines (but they may be an excellent expert about lasers!).

Lastly, fact-checking is your friend. This means going to more than one source that you consider reliable to find information. The more times you can confirm a fact with another reliable source, the more confident you can be that the information is correct.

Interpreting scientific research

Of course, there is the option to go directly to scientific papers to find answers. The good thing about scientific papers is that to get published in a journal, the science is peer-reviewed by other experts in the field and has undergone rigorous scientific processes. However, scientific papers can be technical and hard to understand if you’re not a scientist, and often need to be purchased to read.

If you do have access to scientific research, a few key things to consider include: the size of the study (the bigger, the better), whether the study asks exactly the same question that you are trying to answer , and whether the journal it is published in is a reputable one. It is best to look at multiple papers to get an idea of what a range of scientists understand about a topic, what they don’t yet know, and to give you context. Try finding studies that combine and interpret previous research, which are typically called reviews or meta-analyses. These papers bring together evidence from sometimes hundreds of studies, and do the hard work of summarising your topic for you.

Consider this before you share

Understanding sources takes practice, and the more you do it the more you’ll build up your misinformation detective skills. A good checklist that combines the above ideas comes from the World Health Organization (WHO), which it calls SHARE – Source, Headline, Analyse, Retouched, Errors.

Source: rely on official sources of information, especially when it comes health and medical topics.

Headline: ‘clickbait’ headlines rule the internet, so be sure to actually find out what the article says.

Analyse: question the content: if it sounds unbelievable, it probably is. Try to fact-check it somewhere else. Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence.

Retouched: has an image or graphic being edited or taken out of context?

Errors: if there are lots of typos or mistakes, this may suggest that it is not an official source and has not been carefully checked.

And if you’re not completely convinced that a piece of content is accurate and reliable: don’t share it.

We can all fight misinformation by considering what we share before accidentally spreading misleading or harmful content. The key thing is that more people are aware of and think deeply about where information comes from.

Funded by the Australian Government Department of Health.