Creatures of the deep

Picture an interstellar alien. Perhaps it is an odd looking creature with translucent skin, a bulbous head, multiple black eyes and sharp teeth. You don’t have to go into deep space to find such organisms, perfectly suited to their drastically different environment. Such creatures live here on Earth, a couple of kilometres below the surface of the ocean.

Here are a couple of the beautiful and fascinating animals that we are learning more about. Don’t miss the video at the end of this article to see some amazing footage captured by the team on board the NOAA Okeanos Explorer.

Siphonophores

Siphonophores are colonial animals (organisms that live closely together). They comprise many discrete multi-cellular animals (zooids) directly connected to each other via tissue. The interaction between the individual zooids is so strong that, together, they assume the function of a single, larger organism.

Unlike many other colonial animals, the zooids in siphonophores are specialised to specific roles that benefit the whole colony. For instance, the zooids responsible for attacking prey have hollow, dart-like projectiles to inject their toxins; the zooids responsible for digestion metabolise the prey to feed the whole colony.

Some siphonophores produce light and, while it is not uncommon for deep sea creatures to be bioluminescent, it was a siphonophore that was only the second organism discovered to produce red light (most others produce blues and greens).

Grimpoteuthis

Species in the Grimpoteuthis genus of octopus have relatively large fins on the sides of their mantles that they flap to help them manoeuvre through the water. These fins look a little like the quirky ears of the Disney character Dumbo, which has led to the name of ‘Dumbo octopuses’.

Most of the Grimpoteuthis found have been between 20 and 30 cm long, however there are some that grow bigger, with at least one octopus measuring 1.8 metres in length. The genus is still relatively little understood, however there are 14 known species that live between 500 and 7,500 metres below sea level, which is the deepest of any known octopus.

They are thought to inhabit the deep waters across the globe and several have been found off the coasts of Australia and New Zealand.

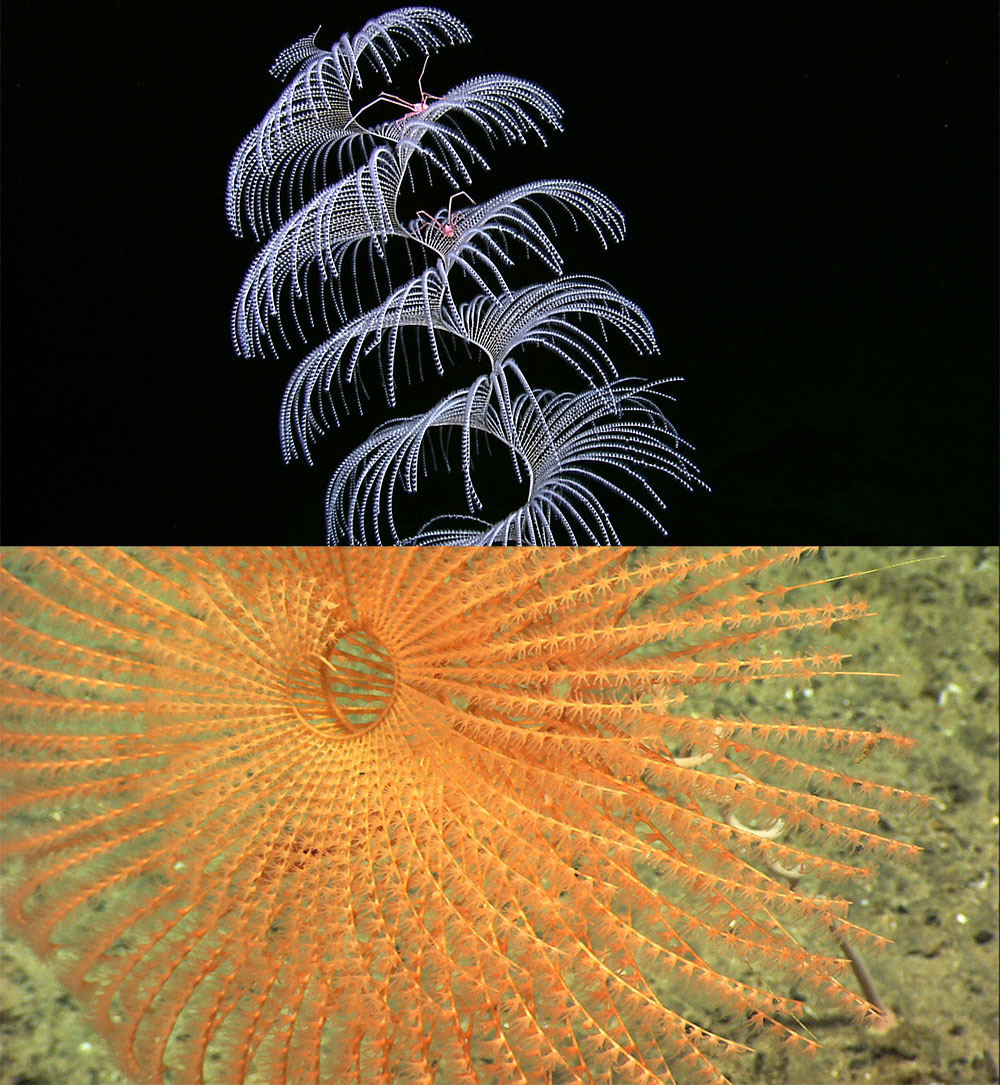

Iridogorgia coral

Like most corals, Iridogorgiae are colonial organisms with many individuals (polyps) forming greater colonies. However, unlike the siphonophores, the individual polyps are all identical in structure and function. They form a spiralling central stem that anchors them to a rock or sea floor. Off this central stem branch a series of flexible limbs, the whole structure somewhat reminiscent of a feather. The coral polyps then protrude from these branches, reaching out into the water. Each polyp is armed with 8 tentacles to catch particulate food from the waters around the colony, making the Iridogorgia ‘octocorals’.

Marine biologists were obviously quite impressed with the beauty of these corals, evidenced by how the corals were named. ‘Iridogorgia’ comes from Greek and Latin route words irodos and gorgia, which roughly translates into 'rainbow gorgeous', and two of the species are named beauty and shine (I. bella and I. splendens).