All about jellyfish stings

If you’ve ever been swimming at a beach in Australia you’ve most likely heard of the dangers of jellyfish stings. Maybe you have even had the unpleasant experience of being stung by the seemingly innocuous, tentacled, translucent invertebrate yourself.

You know it hurts. But how much do you know about Australia’s most dangerous marine stingers?

It turns out even jellyfish experts have much to learn.

What happens when a jellyfish stings you?

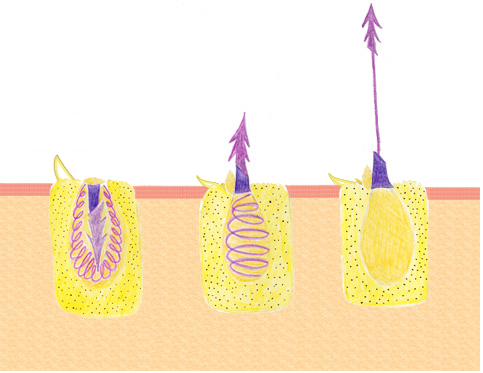

Jellyfish have thousands of stinging cells on their tentacles, which each house a specialised structure called a nematocyst. A sting—which is designed to immobilise prey—occurs when nematocysts fire harpoon-like barbs into the victim. This happens when hair triggers on the tentacles brush against a potential predator or prey—or your leg—triggering the barbs to propel into the victim. It’s a clever and effective mechanism for injecting their venom!

The barb releases toxins, which generally create painful localised reactions in humans. These can also affect various systems within the body such as the cardiovascular and respiratory systems—and may result in fatalities in some cases. The levels and chemical composition of the toxins within each barb, as well as the number of nematocysts fired, results in variation and degree of severity of symptoms.

Species and stings of greatest concern in Australian tropical waters include the major box jellyfish (Chironex fleckeri), bluebottles (Physalia spp.), and a group known as Irukandji jellyfish that can cause serious reactions in humans. The effects of Irukandji stings externally appear similar to anaphylaxis, but are systematically more like an amphetamine overdose. It pays to be aware of the various types of jellyfish and their stings, as differing treatments are required.

Irukandji syndrome presents as nausea, vomiting, back pain and powerful stomach cramps, among other symptoms, including a ‘feeling of impending doom’. It can cause high blood pressure (hypertension) and injury to the heart that may result in heart failure. Currently, there are around 20 species of jellyfish thought to cause Irukandji syndrome in humans. These reactions to jellyfish stings have typically been encountered in tropical Australia, but may happen all over the world, including sub-tropical and temperate regions.

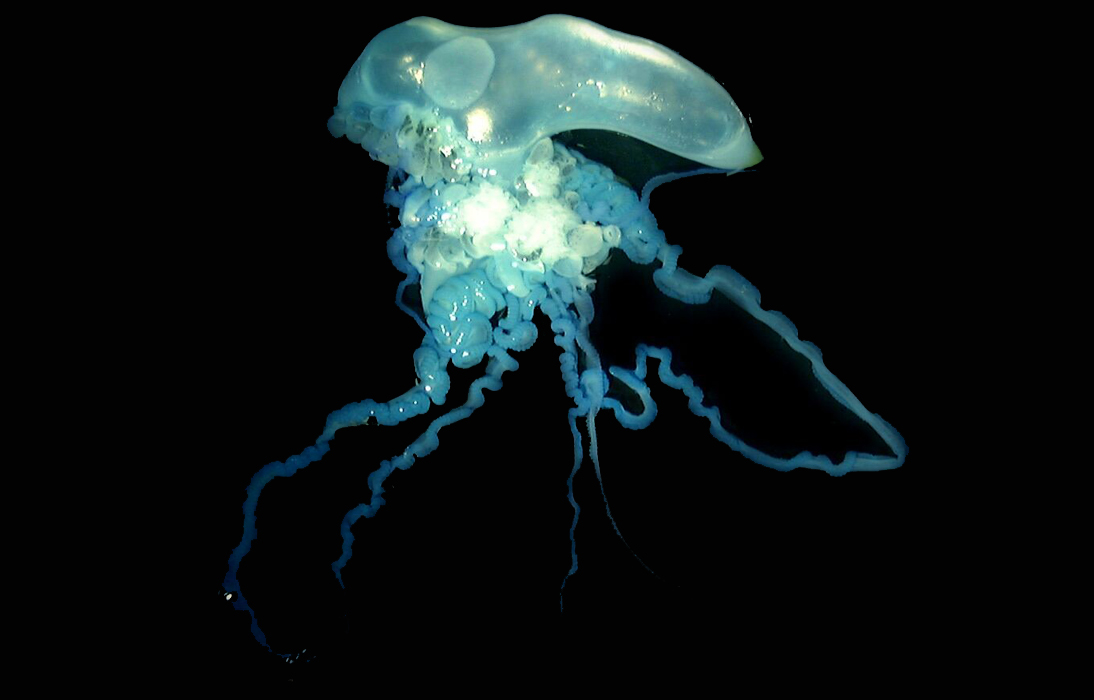

However, not all jellyfish species causing Irukandji syndrome have been named and classified. There is a rare, but potentially deadly stinger which in appearance is very similar to a bluebottle but causes much more devastating reactions. Due to the lack of awareness and understanding of this species, it may often be mistaken for a bluebottle sting. The unnamed species is about the size of a hand, which is considerably larger than the common bluebottle and has multiple tentacles, whereas the common bluebottles have just one. This jellyfish has been reported in blooms off the coast of Australia only every 10 to 30 years. It is so rare that scientists have had little opportunity to observe and classify the mystery species.

What do you do in the case of a jellyfish sting?

While treatments differ depending on the species of stinger (and the locations they are most likely to inhabit), the main elements to act on to treat a jellyfish sting are:

- detaching the tentacles or rinsing away the nematocysts

- neutralising venom effects

- relieving symptoms, including pain.

Everywhere but the tropics the priority is pain relief: washing the affected area with seawater is recommended for helping to remove the tentacles and microscopic nematocysts without releasing further toxins. Washing with freshwater stimulates the remaining nematocysts to discharge, thus injecting more toxins into the victim. Always avoid rubbing the area of a sting.

If there are a lot of bluebottles washed up on the beach or there are blue tentacles present on the skin, it is most likely a bluebottle sting. The pain is instant and sharp. Remove the tentacles using tweezers or (covered) fingers, and rinse the area with seawater. Apply hot water if available to the sting site—this is most easily done by having a hot shower or bath. If hot water doesn’t relieve the pain or isn’t an available option, an ice pack can be used. Seek medical assistance immediately if the victim experiences systemic symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, lower back pain or sweating (these are all Irukandji symptoms, suggesting it might not actually be a common bluebottle sting).

In the tropics, where the stingers are potentially lethal, the focus is on preservation of life. If for any reason you think it could be a box jellyfish or Irukandji sting, or you are not sure of the origin of the sting, douse the affected area with vinegar for at least 30 seconds. This will usually neutralise any microscopic nematocysts that may remain. Seek medical help immediately and note any reactions within the hour following the sting. Perform CPR if necessary.

There is still much to learn about the many classified and unclassified jellyfish species in Australian and other waters. The more understanding we have, the better we will become at treating and preventing these potentially deadly, and just downright painful, stings. As we develop our knowledge we can make better predictions about where they’ll be and when to watch out for them and can have the remedies for treatment prepared and ready for the inevitable marine stings that people experience on our coast each summer.

Disclaimer: This information is not intended nor implied to be a substitute for up-to-date professional medical advice. For the latest first aid recommendations, consult the Australian Resuscitation Council (see Guideline 9.4.5).