How does a global pandemic affect our food supply chain?

Around the world, fears of food shortages during the COVID-19 pandemic sparked panic buying. Despite an abundance of produce here in Australia, supermarket shelves were often bare of groceries. Why? It’s a logistics problem—food supply chains can be long and (some say unnecessarily) complex.

According to the Australian Food and Grocery Council, Australia is capable of producing enough food for 75 million people, three times its own population. While our food supply is considered secure, shutdown measures and transport restrictions put in place to contain COVID-19 have had serious implications for global food security. The UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) says that the pandemic continues to affect agriculture and food production and puts vulnerable populations at risk.

Disruptions to food supplies

Here, we take a detailed look at how a global crisis like the COVID-19 pandemic can disrupt food supply and look at emerging data-based solutions that could make the supply chain more secure.

Primary production

The food supply chain starts with the production of fresh fruit, vegetables, meat, seafood and grains. Natural disasters like droughts have caused ‘supply shocks’ in the past, but COVID-19 has caused problems of a different kind.

Labour shortages are an immediate problem during a crisis. Continent-wide lockdowns can prevent seasonal harvesters from travelling, which can lead to fields of abandoned, rotting crops.

As well as an active workforce, primary producers need essential resources like fertilisers, seeds and veterinary medicines, and any shortages can affect future agricultural production. If proper farming practices can’t continue as normal, this could lead to reduced harvests in later seasons.

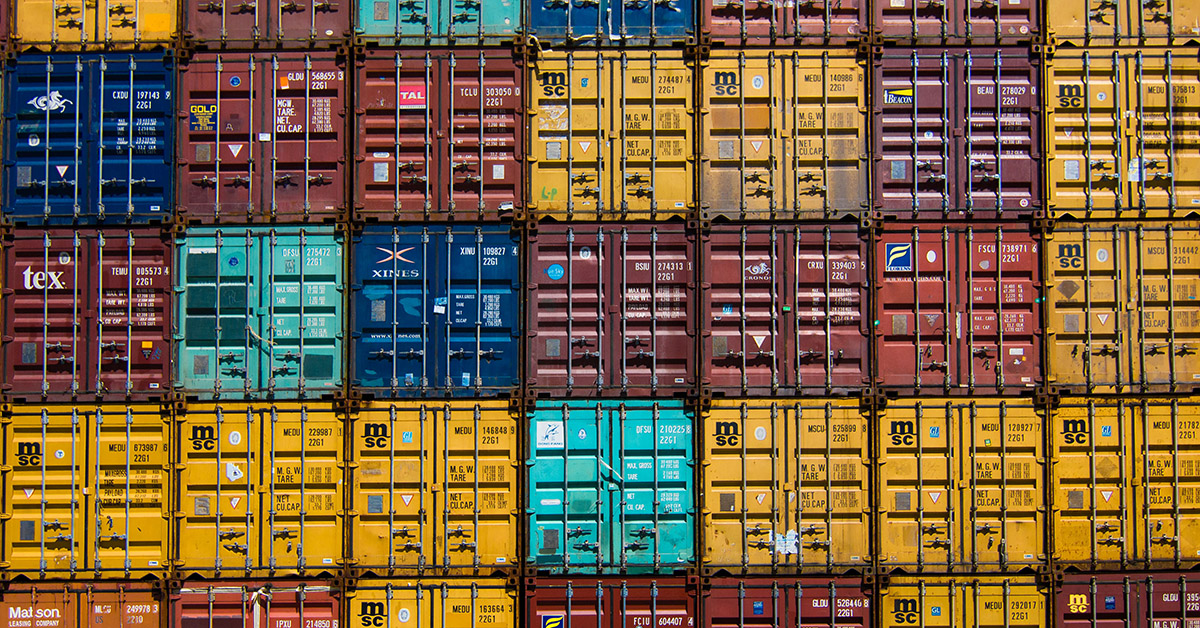

Transportation and warehousing

The safe and uninterrupted transportation of fresh produce, meat and seafood is critical in the food supply chain. A shortage of truck drivers means that products can’t leave the farm, while transport delays are of particular concern for live animal transport and meat supply due to animal welfare issues and food spoilage.

The export market can also be disrupted. If planes are grounded, fresh produce can’t be exported overseas. This means that farmers and exporters can’t access high-value overseas markets, affecting international trade. Sourcing refrigerated shipping containers from China also became an issue during COVID-19 shutdowns.

Wholesale and food processing

Farmers sell a major portion of their produce to wholesale markets for commercial kitchens, but demand falls if pubs, bars, cafes and restaurants close due to shutdowns. Our food supply chains are highly specialised, which often means that wholesale products can’t be diverted to retail because they’re packed in bulk and not labelled in the right way.

Farmers also sell produce to various processed food sectors, such as manufacturers of dried, canned and preserved foods, snacks, confectionery and processed meat—many of which were forced to close during shutdowns overseas.

Retail

Ever wondered how supermarkets can offer customers a choice of more than 40,000 items? It’s by keeping very little in stock, with the bulk of products stored at distribution centres or warehouses. The logistics of replenishing stock is controlled by tracking sales with algorithms that have limited ability to adapt to sudden changes in consumer behaviour, which is known as the ‘just-in-time' concept. That means a sudden rise in demand for certain products—such as pasta, rice and flour—can quickly prove to be unmanageable.

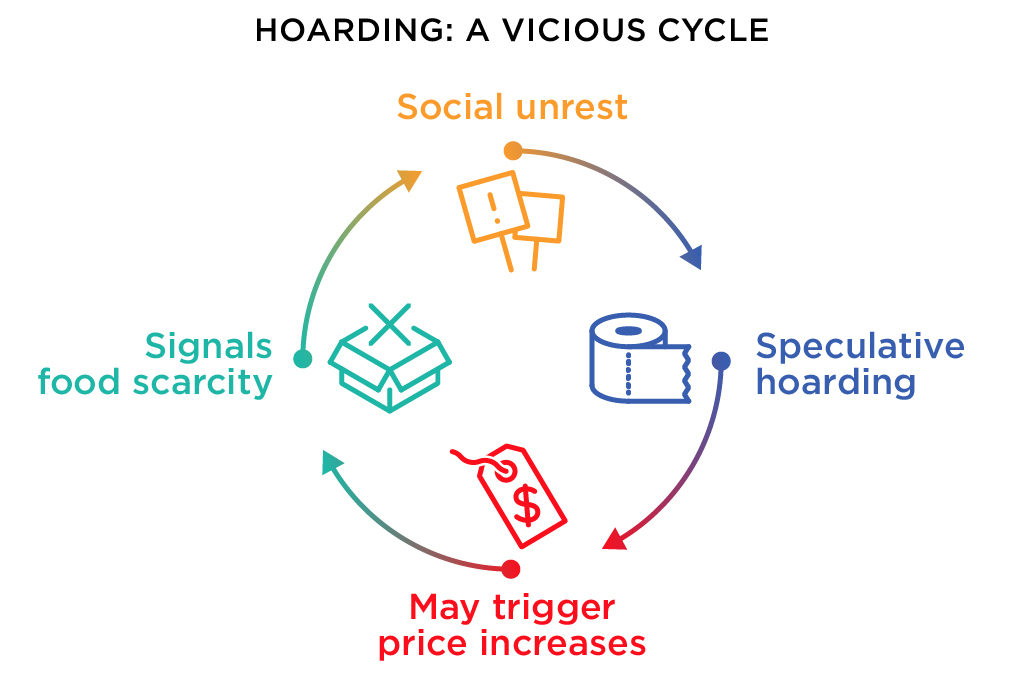

This is exactly what occurred in many countries during COVID-19. If there aren’t enough staff to load, transport and unload products from warehouses, the result is empty shelves. Panic buying can also result in a vicious cycle of shortages and unrest, which is well documented by agricultural economists.

Consumers

Despite fears of food shortages due to COVID-19, our food supply in Australia is highly secure, and concerns about higher retail prices due to COVID-19 may not eventuate either.

However, disrupted food relief services have caused serious adversity for vulnerable households around the world, reinforcing the need for well-connected food donation networks. According to the FAO, developing countries are most at risk from food insecurity: nations that already suffer from chronic hunger and that rely on imported food.

COVID-19 has undoubtedly accelerated changes in consumer purchasing patterns. Consumers are switching to online food shopping platforms and visiting supermarkets less frequently, as well as showing greater preferences for local food with traceable origins.

Sustainable food production

According to the FAO, developing countries are most at risk from food insecurity: nations that already suffer from chronic hunger and that rely on imported food. Populous countries in Asia and Africa are particularly threatened by ongoing climate and health challenges. In the latest State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World Report, the United Nations warns that COVID-19 could push an added 130 million people worldwide into chronic hunger by the end of 2020.

Action on food security and climate change can be achieved simultaneously, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Developing shorter food supply chains means that perishable foods can be quickly transported, which supports local suppliers and lowers environmental impacts. Another approach is agroecological farming practices that promote biodiversity, improve soil and water quality and recycle nutrients and energy.

These sustainable solutions require financial assistance and regulatory agreements from governments and policy makers to help feed an increasingly hot, hungry world.

Crisis-proofing the food supply chain

Even before COVID-19, food supply chains have been in transition due to multiple factors, from trade disputes to climate change. It’s clear that they need to become more resilient, agile and flexible to cope with supply and demand shocks, and new technology and data platforms can help prepare for future disruption.

Solutions for the supply chain: traceability with blockchain

Traceability is the ability to track food products through all stages of the supply chain. It’s incredibly important to maximise efficiency and becomes even more vital in the case of transport delays or contamination tracing. Food industry experts believe that increasing the strength and security of supplier communications is essential to ensure food safety and traceability.

A promising technology to enable traceability is blockchain, a digital platform where users store and share information across a network. This system can give producers, suppliers, distributors, retailers and consumers access to trusted information regarding the origin and state of each product or ingredient. It isn’t yet widely used across the food industry, but has the potential to increase visibility through our increasingly complicated supply chains.

Solutions for producers: online sales

COVID-19 didn’t just boost downloads of food delivery apps. Physical distancing restrictions meant that livestock sales moved online too, through apps that connect farmers directly to buyers. Carrying out auctions via video stream negates the need for the animals to be trucked to saleyards, a hands-off approach that’s better for animal welfare. As their popularity increases, online sales could eventually replace traditional livestock auctions.

Farmers who lost sales when restaurants and cafes closed also turned to e-commerce to sell their products directly to consumers. With numerous examples of farmers adopting tech-based solutions around the world, shorter food chains could become the norm post-COVID.

Solutions for warehousing and transportation: tracking and storing perishable products

During COVID-19, finding warehouse storage space for food products became a challenge. Avoiding bottlenecks like this requires creative storage options, such as compact vertical warehouses closer to cities, which would also help cope with increased demand for online food deliveries.

For the transport of perishable goods, tracking perishables through the cold food chain is essential to prevent a whole shipment going to waste. The latest sensor technology can be instrumental in preventing food waste and compromises to human health, as can smart food packaging that monitors food condition. These solutions are highly applicable to any crisis that affects food supply chains.

Solutions for retail: advanced inventory management

The latest inventory management and replenishment platforms aim to respond faster to changing consumer behaviour—crucial to avoid bare shelves during unusual events. They keep inventory data up-to-date using automation and real-time tracking technologies, such as radio-frequency identification and Internet-of-Things capabilities. Using advanced predictive tools, such as improved data processing with artificial intelligence and machine learning, retailers can better respond to disruption.

A crisis like COVID-19 has taught us that our complex food supply chains need greater transparency and flexibility to prepare for future disruptions. Making food supply chains more agile, resilient and adaptable is essential to protect the economy and feed the world.