How to make chocolate

Ah, chocolate—sugary-sweet, velvety, full of flavour and the end result of a whole lot of chemistry. From the moment the cacao pods are picked to the time you place that first delicious square of chocolate on your tongue, chemistry is playing a part, influencing taste, colour, texture and aroma.

So what’s involved in getting from raw ingredient to that delicious final product?

In Australia, the Food Standards Code defines chocolate as ‘a confectionery product characterised by the presence of cocoa bean derivatives,’ namely cocoa liquor, cocoa butter and cocoa solids. The percentages of these components can vary significantly between products.

Cacao (also known as cocoa) comes from the cacao tree (Theobroma cacao), which grows in warm, tropical climates generally within 20 degrees of the equator. Each cacao pod contains around 30 to 45 seeds (often called beans) and chocolate is made from the nibs of these seeds—the cotyledons.

So … cacao vs cocoa? Same thing spelled differently? Apparently not.

Cacao refers to any food products derived from cacao beans, such as the cacao nibs, butter, powder or paste. Generally, the term is used to describe raw, unprocessed chocolate products that have not been exposed to high heat. Cocoa, on the other hand, refers to cacao that has been roasted. This form (i.e. cocoa powder) is what you more commonly buy in the supermarket to use in hot chocolate or chocolate cakes.

When cacao seeds are first removed from the pod, the seeds are bitter and rough, and not at all chocolatey. To obtain the flavour we know and love, several chemical transformations must first occur.

The first step is fermentation and curing, which must begin within 24 to 48 hours of pods being opened and generally lasts 5–7 days. The beans are piled in heaps or placed in special boxes. Microorganisms quickly get to work removing the pulp from the beans. Yeasts grow on the pulp, converting the contained sugars into ethanol. As bacteria move in, they oxidise the ethanol to acetic acid and then to carbon dioxide (CO₂) and water. This produces heat and raises the temperature. The pulp breaks down as both lactic acid and acetic acid are produced. The acetic acid eventually breaks down the cell walls of the bean, and substances that were previously kept apart can now mix.

The subsequent changes within the bean, known as the curing process, involve enzyme activity, oxidation and the breakdown of proteins into amino acids. Fermentation develops important flavour precursors, which are the beginnings of the unique chocolate taste and aroma we know. It also browns the beans.

After fermentation, the beans are cleaned, sorted, graded and then roasted. During roasting the vinegar smell produced by fermentation is removed. The bean shells become brittle and the colour of the beans darkens. The process converts the flavour precursors within the bean into compounds such as aldehydes, esters, lactones and pyrazine, which give chocolate its aroma and flavour.

A winnowing machine removes the bean shells and leaves just the cacao nibs. The nibs are then ground and liquefied into a cocoa liquor. Heavy-duty presses can further process and separate the liquor into either fat-rich cocoa butter or cocoa solids (that are ground to make cocoa powder).

It used to be that only cocoa solids were used and the fatty cocoa butter was discarded. However, in 1847, Joseph Fry discovered that reuniting cocoa powder with some of the leftover cocoa butter made it into a solid that could be easily melted and resolidified at room temperature without any change in its qualities. Even butter can’t do this. Additionally, this new hybrid product could quickly take the form of anything it was poured into—and so the chocolate bar was born. Whether he was visionary or simply thrifty is unclear. However, his revolutionary contribution to culinary arts is possibly the most important product to ever come out of England, exceeding even fish and chips and cheddar cheese.

Today, after the cocoa solids are extracted from the butter, they are carefully blended back together. Different varieties of chocolate are made by adding different amounts of cocoa butter back into pure liquor. Other ingredients such as sugar, vanilla, milk solids, additional fats (found in cheaper chocolates) and other flavours are also added during this step.

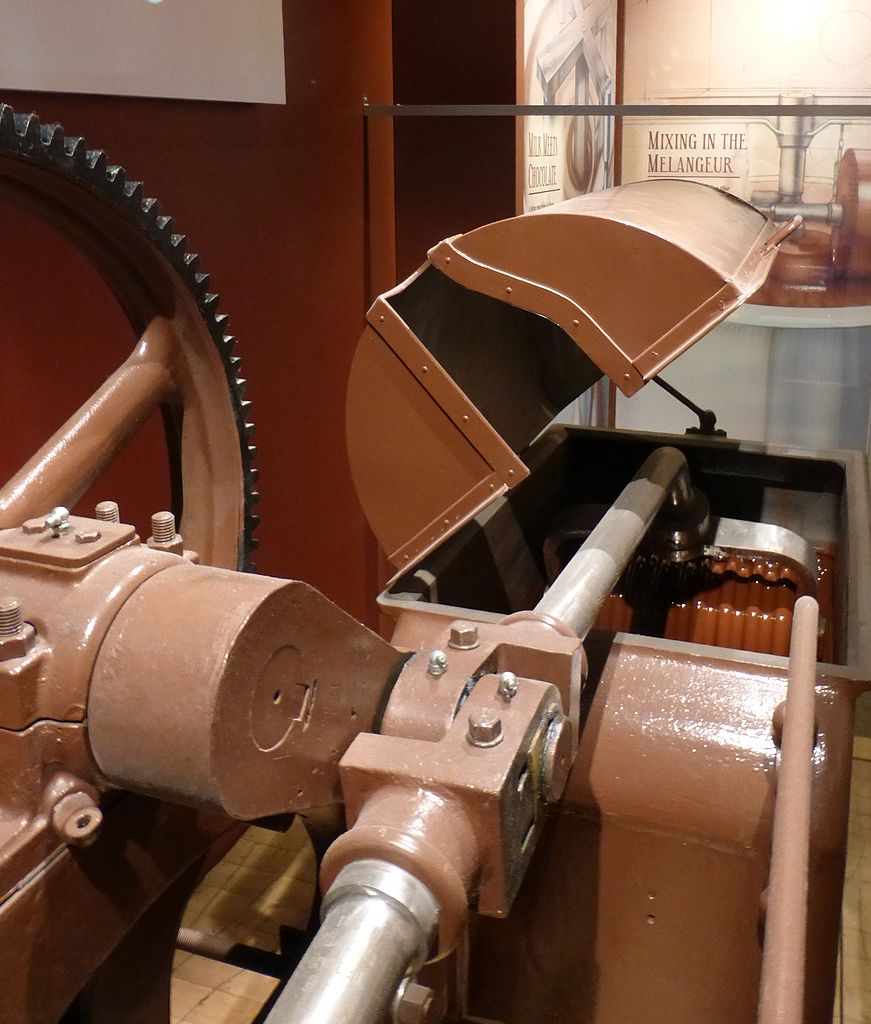

However, this blended chocolate can still be rough and a bit gritty, so next comes a refining process, also known as conching. This slowly mixes the ingredients together under heat while at the same time continuously grinding them to create a silky smooth finish. This breaks down the sugar and cocoa into particles too small for the tongue to feel. The longer the chocolate stays in the conching machine, the smoother the end-product. Cheaper chocolate may only take around four hours, while the more expensive varieties can be conched for anywhere up to 72 hours.

Tempering—the process of varying the temperature at which chocolate is cooled—comes after conching, and is the essential step in producing many of chocolate’s most-desired qualities. Its smooth shine and rich texture, its ‘snap’ and the way it melts in your mouth are all the thanks to the formation of just the right type of chocolate crystal, which is created during the tempering process

To make Dutch chocolate, there's an extra step involved. Cocoa solids are alkalised to make them less bitter and less acidic and therefore easier to work with in cooking. This whole process is known as 'dutching'. It also makes Dutch chocolate appear dark, even though it also destroys some of the flavonoids found in dark unprocessed chocolate.

So now you have a basic understanding of how chocolate is made and why following the above steps is so important. Without them, and the chemical reactions they include, our chocolate would taste like coffee grounds ... and there would be no chocolate Easter eggs!