Making memories

Memories are a big part of what makes you, ‘you’. The smell of your mother’s perfume, the taste of grandma’s pie, the first time you said ‘I love you’ or the music you walked down the aisle to—being able to remember the people, places, events and experiences that have occurred during your lifetime shapes who you are, ties your past and present together and gives you your sense of self.

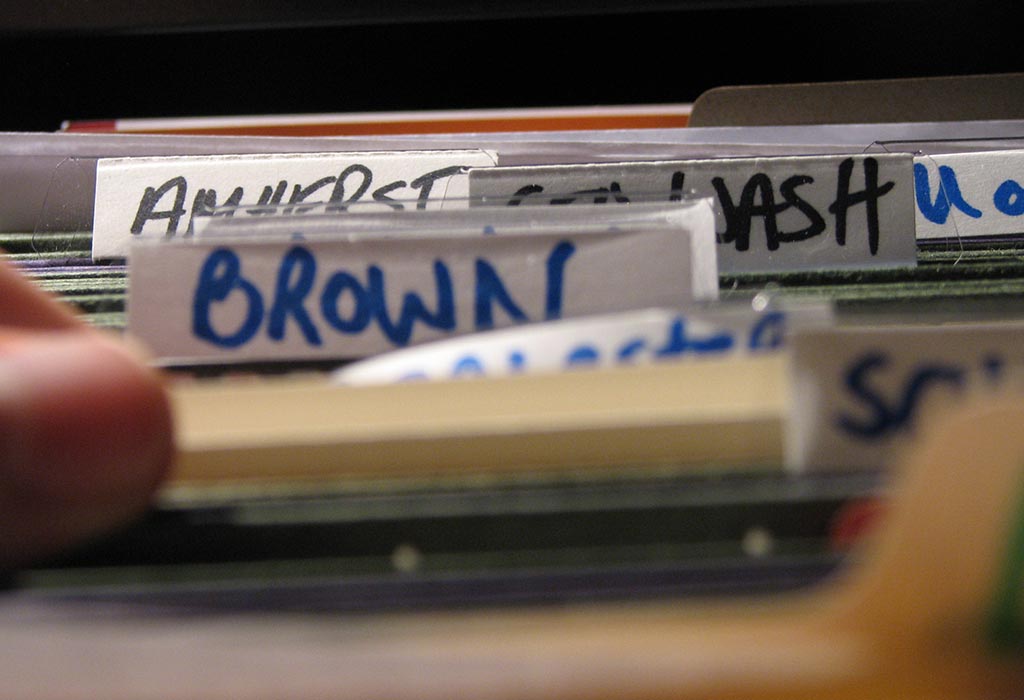

What is memory, exactly? Cartoons might like to portray our memory as a filing cabinet, where all our memories are filed away one by one. But memories are not stored in this way—in fact, we don’t have ‘single’ memories at all. Instead, these recollections are complex constructions of multiple memories, involving several different parts of the brain.

Rather than a filing cabinet, a better representation of our memory would be a complex web, where the multiple strands represent the different elements of a memory (visual, spatial, emotional, auditory and so on) which eventually come together at the connection points to form a ‘complete’ memory.

But this still doesn’t explain what memory is. Studying how we form, recall and forget memories is a complex science with many different suggested frameworks for explaining how it all works. Perhaps the most influential model for understanding memory-making is the ‘standard model of memory’ consisting of three main systems: sensory, short-term, and long-term memory.

How we make memories

Sensory memory

Thanks to our senses (sight, hearing, touch, smell and taste), we constantly receive information about the world around us. This information is automatically stored for a fleeting moment in our sensory memory, which largely takes place in the various sensory areas of our brain. Things that we see (iconic memory) will typically be retained for somewhere between half a second to two seconds, while things that we hear (echoic memory) can persist for up to four seconds.

If you’re paying conscious attention to a stimulus, such as the words spoken by the friend you’ve just met in a café, the information will be encoded (transferred) into your short-term memory. If you’re not paying attention, the information in sensory memory is discarded, which is why you probably won’t remember the rest of the customers’ chatter surrounding you, or the colours of their clothing.

Working memory and short-term memory

Think of your friend telling you a story. As they speak, you need to remember enough of the content of each sentence to make sense of what they say and to decide how to best respond. This information is held in short-term memory just long enough for you to process it in your working memory.

‘Working memory’ and ‘short-term memory’ are terms that often get used interchangeably but mean subtly different things. Think of short-term memory as being a temporary storage area for information, while working memory is where active processing and manipulation of that information takes place.

Working memory isn’t just responsible for processing brand new information and encoding it in our long-term memory storage. It is also responsible for actively retrieving already-learned information from long-term memory and relating it back to the new information streaming in. Those long-term memories may end up being slightly modified as a result.

We can only hold small amounts of information (typically about four or five items) in short-term memory for a few seconds to a minute. We can increase this holding capacity by ‘chunking’ information, such as remembering a string of numbers by grouping some of them together, and by rehearsing information by repeating it over and over. If we start to think about the relationships between new and previously-learned information (called ‘elaboration’), this new information is more likely to be transferred into long-term memory storage.

Long-term memory

Long-term memory is just that—the place where memories are consolidated and stored for long periods, ranging from days to years (or sometimes, indefinitely). It seems that our long-term memory can potentially store an almost unlimited amount of information, with some researchers questioning whether we ever forget anything (it’s the retrieval of the memory that is the problem!).

While short-term memory relies more on acoustic (sound) and visual information storage, long-term memory is generally more focused on storage and retrieval by association, based on the emotional or physical triggers present when the memory was made. As new memories are made, they are stored and consolidated (stabilised) by changing the strength of connections between neurons. Sleep (especially slow-wave sleep), during which memories are reactivated and rehearsed, appears to be especially crucial for the consolidation of memories—which is one reason why pulling an all-nighter to study for an exam the next day is not a wise strategy.

Once an experience makes its way into long-term memory, it is not stored there in a permanently fixed state: you may alter the memory each time you retrieve it. When a memory is retrieved, it undergoes a period of reconsolidation, during which details given by others, similar memories, or the present experience can be added. Our memories are not infallible or always reliable.

Researchers still do not understand the full complexity and capacity of human memory. The ‘standard model’ will keep changing over time as we learn more about how memory works, how to improve it, and what to do when things go wrong. The human brain is a remarkable machine.