Understanding different blood types

When it comes to what blood type (or blood group) you have, it’s all about the antigens—the various sugars and proteins on the surface of our cells, including our blood cells. Which antigens you have or don’t have on your red blood cells determines your blood type. Antigens are genetically determined—inherited from a combination of your parents’ genes.

There are many different blood type systems, but most people will be familiar with the two main blood groupings—the ABO and Rh (or Rhesus) systems. These systems lead to the eight commonly known blood groupings.

The ABO System

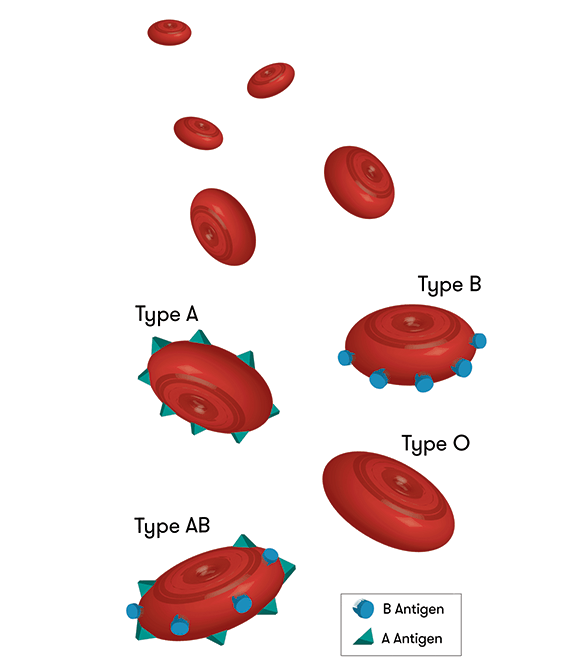

Whether your blood type is A, B, AB or O depends on whether you have, or don’t have, certain antigens (named A and B) on your red cells.

The presence or absence of A or B antigens gives us four main blood types:

- A type blood has only A antigens on red blood cells

- B type blood has only B antigens on red blood cells

- AB has both A and B antigens on red blood cells

- O has neither A nor B antigens on red blood cells.

The Rh System

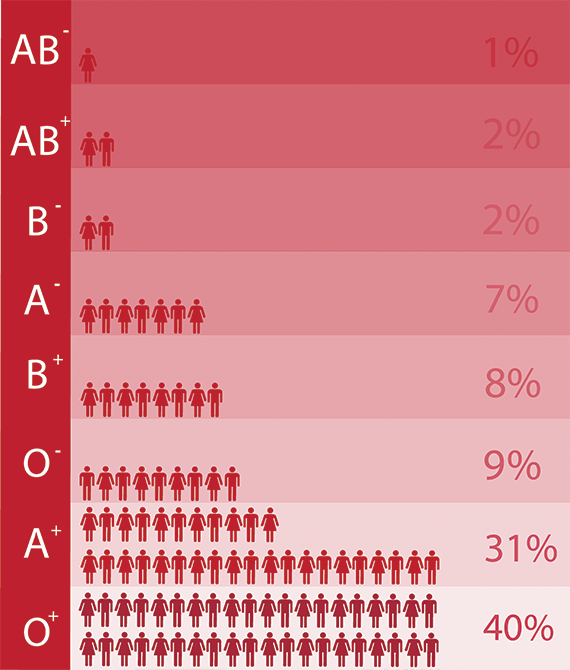

Like the ABO system, the positive or negative component of your blood type refers to molecules being present or absent on the surface of your red blood cells. The full Rh blood group system includes around 50 different red blood cell antigens, but the most important one is a protein called RhD. If you have the RhD protein on your red blood cells, you’re Rh positive. If you don’t have it, you’re Rh negative. Most Australians are Rh positive.

Why does blood type matter?

Blood types are most important to know if you are needing a transfusion, but it appears that different blood types may have an impact on certain diseases.

For example, if you are blood type O, you may be more likely to be asymptomatic if you’re infected with malaria. On the other hand, type O people tend to be more prone to infections of Helicobacter pylori, the bacterium that causes stomach ulcers, where AB blood type individuals are less prone. A recent Japanese study has also linked blood type O to a higher risk of death after experiencing severe trauma, possibly due to having lower levels of a particular blood clotting factor.

There may even be some links to certain cancers and other infections like HIV and Hepatitis B.

These correlations may not be due to the actual blood type, but to the absence or presence of antibodies in people with certain blood types, or even other direct effects such as the antigen being recognised specifically by the pathogen.

Could your blood type change?

So, considering some of the potential links to disease, you may be tempted to ask if you could change your blood type.

This wouldn’t normally happen, but it can for some people after a bone marrow transplant. This is because most of your red blood cells are made in your bone marrow. If the marrow donor has a different blood type, your blood type will eventually change to the donor's type.

However, it’s definitely not worth the bone marrow transplant procedure to slightly reduce your risk of some cancers or malaria—it’s far easier to eat a balanced diet, exercise regularly, and sleep under a mosquito net.