What is immunisation?

We have a lot to thank immunisation for. Although you may not feel too thankful as you roll up your sleeve for a jab, immunisation protects not just yourself from some nasty (and sometimes fatal) diseases, but your family and community as well.

You can think of immunisation as being a ‘dress rehearsal’ for your immune system, preparing it to fight off real infections more efficiently and effectively should your body encounter them in the future. But how, exactly, does this whole process work?

Lines of defence

Your body has several different lines of defence to protect itself from invading pathogens (microbes that can cause an infectious disease). Your skin and mucous membranes are the first and most basic barrier against them.

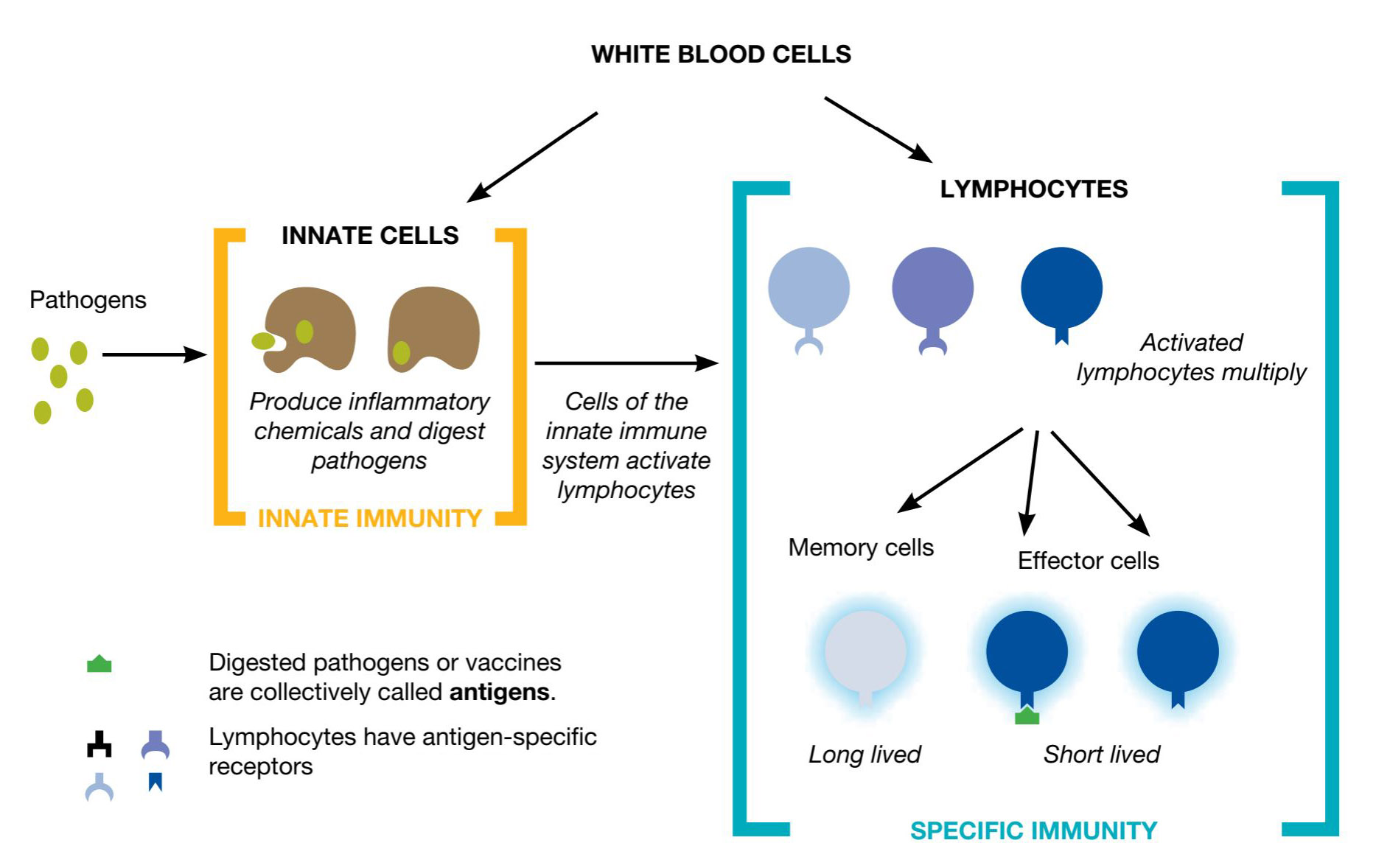

If an invading pathogen gets past this physical barrier, our second line of defence—the innate immune system—kicks in, where our white blood cells start getting involved. We have several different types of white blood cells in our bodies and while they’re all involved in fighting off infections, they each have slightly different roles.

First up, the white blood cells that are part of our innate immune system respond very quickly to invading pathogens or other foreign particles (also called antigens) that they detect. You can think of these cells as being the ‘pathogen police’: they’re always on guard and the first ones on the scene to react within minutes when an invader breaches the body’s outer defences. Their role is to track microbes down, capture them and then engulf them, leading to their destruction.

After that, it’s time for the pathogen police to bring in the ninja warriors: another set of white blood cells, called lymphocytes. These cells are part of our specific (or adaptive) immune system and are the third line of defence. Unlike the more generalised response of the cells of the innate immune system, which respond the same way to every invader, lymphocytes have the power and specialised means to mount targeted attacks.

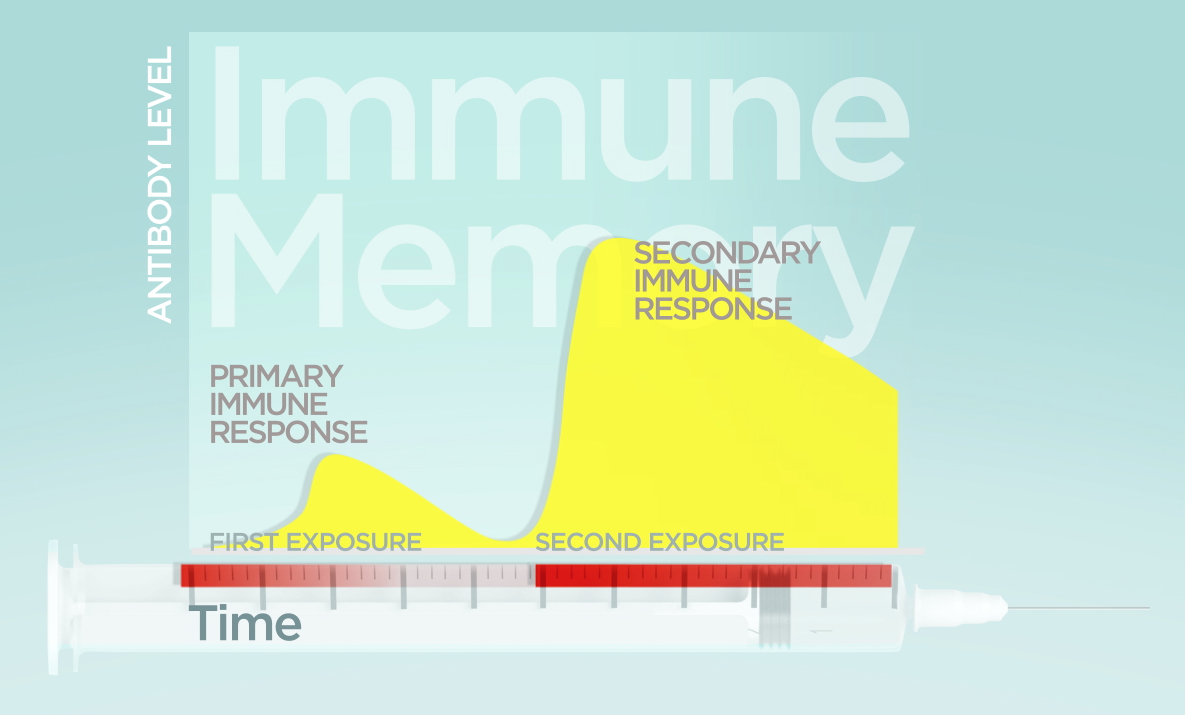

Lymphocytes know if they’ve encountered a particular invader before because they have special antennae on their surface known as receptors that will only respond to one particular target antigen. Some lymphocytes have the job of producing the right antibodies to target a pathogen or the toxin produced by it, while other lymphocytes go in for the kill, destroying pathogen-infected tissues. They’ll then remember this antigen for next time so that they can mount a faster, bigger and more sustained attack against the invaders before they can cause serious harm.

It’s this ‘memory’ ability of the immune system that immunisation so cleverly exploits. A successful vaccine introduces the immune system to disease-specific antigens, enabling it to remember the best way to fight off the invader if it turns up.

The difference between a vaccine and an actual infectious particle, though, is the fact that a vaccine contains a dead or weakened form of the pathogen, so people do not catch the infection from a vaccine. In its weakened form, the pathogen generally cannot replicate and spread through the body to cause the nasty symptoms and potential lifelong complications associated with a full-blown infection.

Immunisation is an important part of keeping ourselves healthy and safe. Without it, we’d risk exposing ourselves to many horrific diseases that have caused incredible grief to millions of people across the globe, like diphtheria, tetanus, polio or whooping cough. So, while there may be a bit of a sting when you roll up your sleeve for a shot, it’s a small price to pay compared to the consequences of getting very, very, very sick.