What we can learn from prehistoric poo

Scientists usually try to avoid crappy results. But when it comes to fossils, number twos are number one. The technical (and polite) term for fossilised poo is ‘coprolite’. And perhaps surprisingly, coprolites are rich sources of information: we can figure out migration patterns, what the poo-producer ate and what sort of microbes lived in their gut.

But preserved poo is rare. This is because it is chock-full of microbes—each milligram of faeces contains more than a million bacterial cells. Lots of bacteria means it decomposes quickly and it’s unusual to find well-preserved coprolites except in very dry or very cold conditions.

The origin of faeces

Dinosaur coprolites have been dated back to the Cretaceous period (146–66 million years ago). The oldest known fossilised poo (from an animal) uncovered so far dates to the Early Cambrian period, more than 480 million years ago.

From this prehistoric poo, scientists have inferred possible predator–prey relationships of early ecosystems. Bits of partially-digested plants and animal bones provide clues about ancient animal diets. For example, dinosaur dung from 65 million years ago revealed that dinosaurs munched on grass—a surprising discovery, given scientists previously thought that grasses co-evolved with mammals and weren’t present during the dinosaur age.

Meanwhile, the oldest known hominin coprolite samples date back to around 50,000 years ago. Bits of pollen, specific molecules and parasites can reveal the diets of different cultures.

For example, a study of Neanderthal coprolite found in the El Salt site in southern Spain found traces of chemicals that indicated Neanderthals ate not only meat, but also significant amounts of plants.

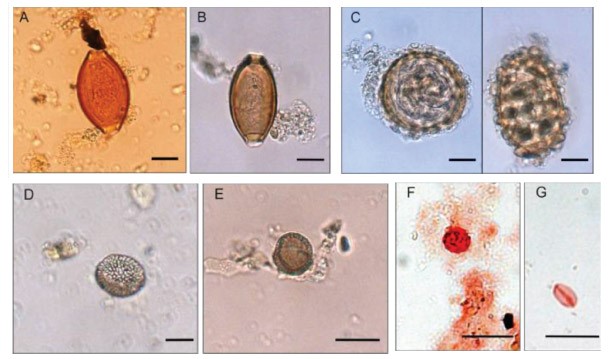

Parasites encased in coprolites provide diet clues too. Coprolites found on an island of Puerto Rico and dated to between 5 and 1170 AD contained different types of parasites. Some coprolites contained only parasites associated with maize and fungi (basidiomycetes), while the others had parasites associated with fish species. This suggested that the coprolites came from two distinct communities of people with very different diets.

In the American Southwest, coprolites associated with an Anasazi archaeological site contained tissue remains that could have only come from consumed human flesh—a sign of cannibalism.

Microbiome mysteries

The trillions of microbes that live in and on your body—collectively called the microbiome—play a huge role in your health and wellbeing. Through poo, scientists can trace changes in our microbiome over time.

One prominent study of fossilised poo describes the microbiome of coprolites found in three distinct environments: southern USA, northern Chile and northern Mexico. When compared to modern data, ancient microbiomes were a closer match to those of today’s rural communities than to urban dwellers.

Scientists have inferred further microbiome change thanks to medieval loos. Excavations in the Belgian town of Namur uncovered latrines from the Middle Ages, complete with barrels of human waste that had been sitting around for nearly 700 years. Samples from these barrels of poo showed evidence of bacteriophages. These are viruses capable of transferring genes between bacteria and are responsible for the development of antibiotic resistance in some bugs. They carried an increased diversity of the genes compared to modern humans’ bacteriophages, suggesting that the natural inbuilt defences of our gut bacteria may have weakened in modern times—perhaps as a result of modern sanitation and hygiene practices.

Studying ancient remains involves more than just bones. It’s amazing what scientists can decipher from the clues inadvertently left behind in excrement relics.