Women's health: we need the full picture

It’s International Women’s Day: a day where the world reflects on the role of women in societies throughout the world, looking for areas where we can improve the way women are treated and celebrating progress. So where does science fit in to this? How has science worked to make women’s lives better?

There’s a lot to celebrate.

The contraceptive pill, developed and tested through the 1950s and first released in the US in 1960 and in Australia in 1961, provided women with a simple and reliable way to control pregnancy, leading to higher rates of education, workplace participation and sexual liberation and autonomy. Research examining the occurrence of toxic shock syndrome associated with tampons found that all-cotton tampons do not lead to the production of the toxic shock syndrome toxin. Improvements in breast cancer screening and treatments have been achieved, and hormone replacement treatments developed. Maternal deaths worldwide decreased by 30 per cent over the period 1990–2014.

But there's more to do.

Clearly, science has achieved some great outcomes, but it’s been an interesting journey. Acceptance that women’s health extends beyond the reproductive system, and that there are more differences between men and women than just the obvious ones, has facilitated the development of treatments and medical applications that suit both men and women.

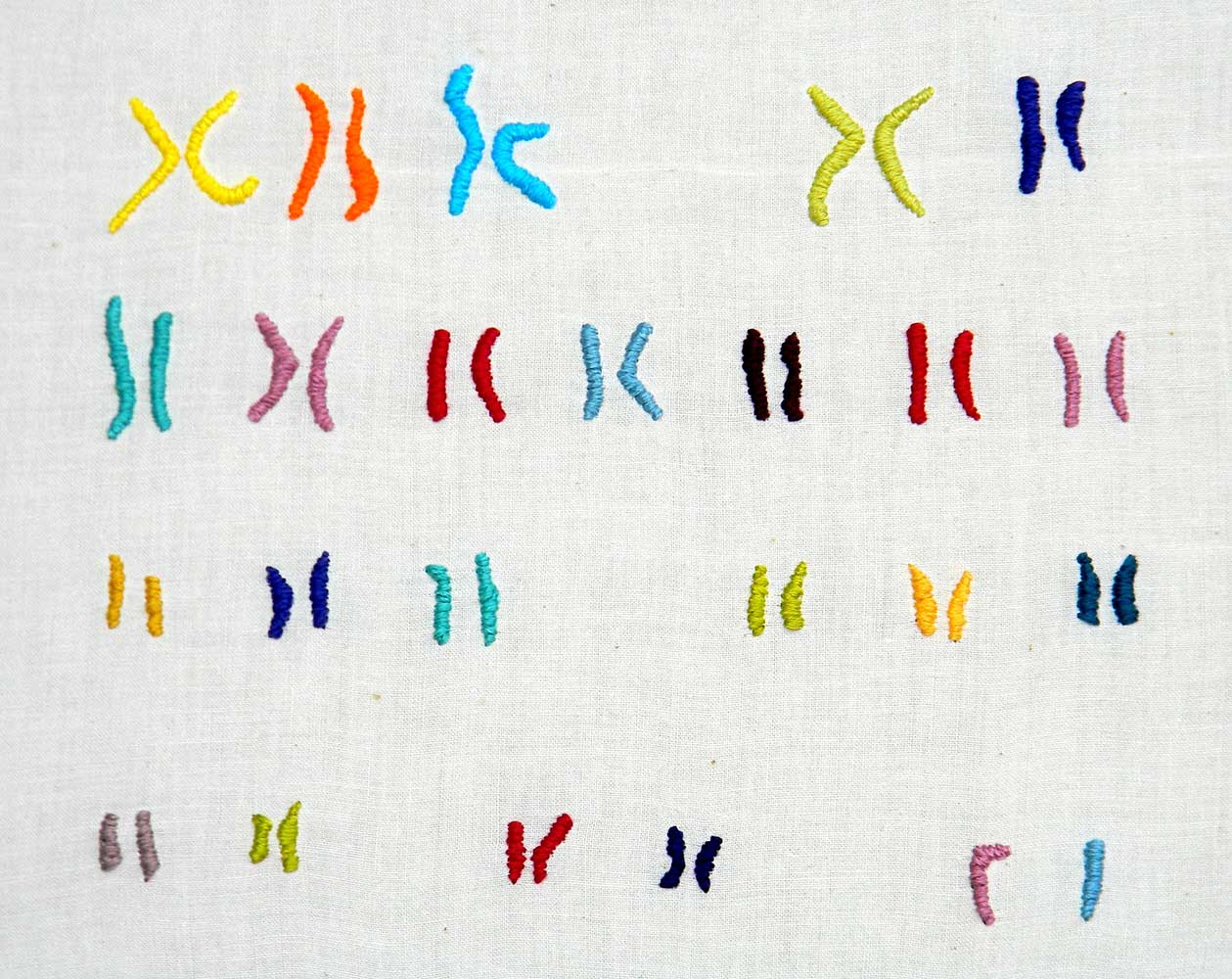

A complete set of all our DNA is found within nearly every cell of our body, including the chromosomes that determine our sex (XX for female, XY for male). It was thought that these chromosomes merely decide what sort of reproductive organs we’re born with: the ‘sex-determining region Y’ gene (SRY) found on the Y chromosome is responsible for triggering the development of testis, and following this, the hormones produced by the male and female reproductive organs were considered primarily responsible for the differences between men and women. However, more recently, scientists have come to appreciate that there are 26 other genes found on the Y chromosome, and it’s quite likely that these genes interact with other genes throughout our bodies.

For example, more than 6,500 genes in our bodies have different levels of activity between women and men. While most of these are related to our reproductive systems, some affect muscles, the heart and even the brain. The incidence and impact of some diseases are markedly different in women and men—about three times as many women as men suffer from multiple sclerosis, while around twice as many men as women suffer from Parkinson’s disease, which manifests differently in men and women. Differences have also been seen for heart disease, osteoperosis, diabetes, obesity, mental health and infectious diseases.

Despite this, there has been a historical bias towards using males in clinical research, including testing and human trials. This may have arisen from good intentions. The US National Research Act of 1974 (implemented following the infamous Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment) resulted in women of childbearing age becoming ‘protected subjects’ to protect both them and foetuses. However, it was also thought that men provided a more straightforward and consistent subject, free of the complications of women’s fluctuating hormones, and that the results derived from male subjects could simply be also applied to women.

The majority of medical research—excluding ‘women’s health’ which essentially became synonymous with studies of the female reproductive system (breasts, ovaries, the uterus)—used the male body as the standard. Cell lines used in labs were male cells, the animals used in animal trials were males, and human clinical trials were nearly exclusively comprised of men. Results from men were simply extrapolated to women.

But in the 1980s, people realised that women patients’ needs were being neglected. In 1986, the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) introduced a policy to increase the inclusion of women in human clinical trial studies, which was made into law by Congress in 1993. In 1998, the US Federal Drug Administration required pharmaceutical companies to provide information regarding a drug’s efficacy and safety based on the patient’s sex (as well as age and race).

While progress has been made at the human clinical trial stage, with women now well represented in US clinical trials, it’s taking a little longer to progress from a bias towards using male animal models used in the study of disease and drug testing. To overcome this bias, in 2014 the NIH introduced a policy where researchers are expected to report results taking sex differences into account, which requires study of both male and female animals.We’re yet to introduce similar regulations here in Australia, but the Therapeutic Goods Association does ensure all drugs and medications are thoroughly tested before allowing them on the market.

There are recent examples that indicate these changes were warranted. Many millions of prescriptions for the drug Ambien, which helps people with sleep disorders, have been dispensed in the US. But in 2013, after more than 20 years of the drug being on the market, the US FDA recommended that the dosage should be halved for women, as it was found their bodies metabolise the drug much more slowly than men. This leaves them drowsy during the following day. This issue was only brought to light following a report that examined road crashes associated with the use of the drug.

In another example, the leading cause of death for both men and women is cardiovascular disease, which can be a killer for both. However, the way a heart attack manifests in women is often different than in men. Men (and some women) generally describe crushing chest pain—this is deemed ‘typical’. But more often than not, women describe ‘just not feeling right, tired, short of breath’, symptoms that are much easier to ignore or not take as seriously, or even misdiagnosed. In the US, more women than men die within 1 year following a first heart attack. Within the 5 years following a first heart attack, 47 per cent of women die or suffer other complications such as heart failure or stroke, compared to 36 per cent of men.

While it’s always going to be difficult to separate the effects of sex and gender (the way women view their own health, interact with and are treated by their doctors as compared to men is grounds for a whole separate article!) we can look at the disparities between the way heart disease presents and is treated based on fundamental physiological differences between women and men. The blood vessels surrounding the heart are smaller in women than in men, and disease develops in these blood vessels differently. Yet the tests to determine if a person is at risk of heart attack were designed and developed in men, meaning they are sometimes less accurate in predicting women’s risk compared to men.

So, while we should celebrate all that science has done to improve women’s lives over the years, it must also be appreciated that true equity starts by considering both female and male anatomy, physiology and metabolism, because they can be fundamentally different. Equal, but not the same.