Science in Australia

- Australia contributes to the global scientific endeavour with research strengths in disciplines ranging from the health and medical sciences, to agriculture, space science and computer science.

- A strong research sector requires support of the full spectrum of research activities; from basic research, which is focused on knowledge development, through to translational research, which aims to deliver new products and processes.

- In Australia, scientific research predominantly occurs in universities, and the workforce is mainly comprised of research students.

- Australians depend on science and research to increase productivity, achieve sustainable economic growth, create jobs and improve national wellbeing.

- Estimates suggest that scientific research contributes $185 billion per year to the economy and supports 1.2 million jobs.

- Insecure career prospects and a challenging research culture mean that Australia risks losing its highly-skilled researchers as they seek opportunities overseas or leave research altogether.

Science is the ongoing pursuit of knowledge of the world and universe. Science uses a systematic methodology, based on evidence, to deepen our understanding and knowledge. This knowledge enables us to enjoy, and continue to build on, the advanced civilisation we have created.

Australia is an important part of the global scientific endeavour. Australia’s contribution to the scientific effort is significant and highly valued globally. With just 0.3 per cent of the world’s population, we have contributed to more than 4 per cent of the world’s published research. We are also known for our willingness and ability to work with scientists in other nations to achieve greater outcomes.

Australian research is extensive and our best researchers cover many disciplines, which include agriculture, environment and ecology, geoscience and engineering. Based on higher education investment in research and development (R&D), Australia’s top three research areas are the medical and health sciences, engineering, and biological sciences, and our research output reflects this. However, when comparing our research outputs to that of other nations, we are a world leader in astronomy, physics and computer science.

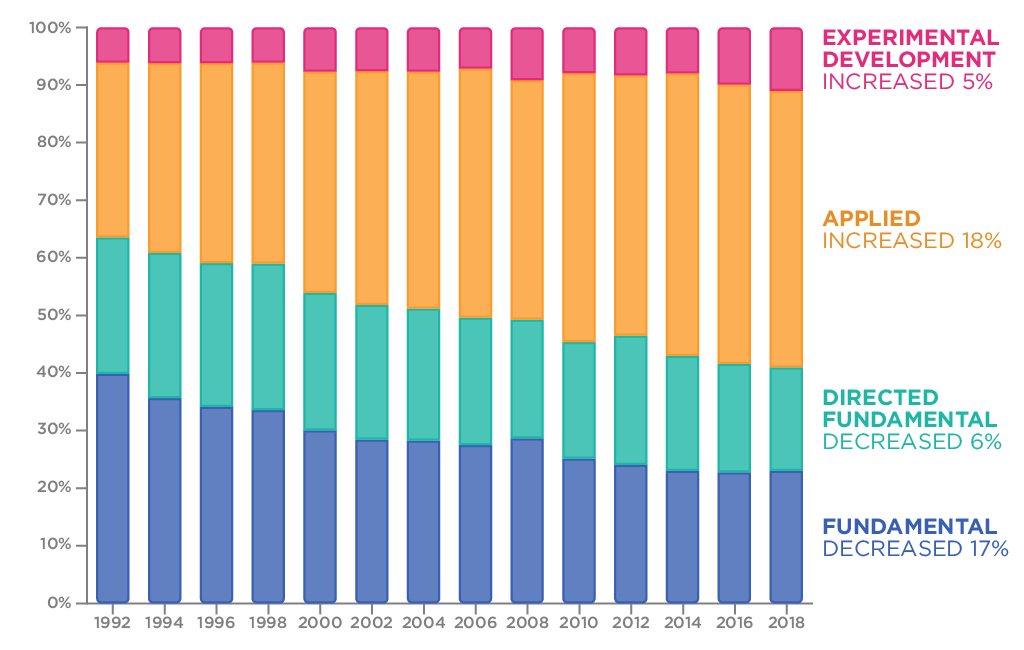

Research and development activities in Australia are classified into four broad categories (names in parentheses are as defined by the Australian Bureau of Statistics):

- Fundamental (pure basic): experimental and theoretical work undertaken to acquire new knowledge without looking for long-term benefits other than the advancement of knowledge

- Directed fundamental (strategic basic): experimental and theoretical work undertaken to acquire new knowledge directed into specific broad areas in the expectation of practical discoveries

- Applied: original work undertaken primarily to acquire new knowledge with a specific application in view. It is undertaken either to determine possible uses for the findings of fundamental research or to determine new ways of achieving some specific and predetermined objectives

- Experimental development: systematic work, using existing knowledge gained from research or practical experience, which is directed to producing new materials, devices, policies, behaviours or outlooks; to installing new process, systems and services; or to improving substantially those already produced or installed.

Shift in funding priorities

Although Australian science covers the full spectrum of research activities, recent trends in government funding to support work with anticipated practical and commercial outcomes has meant that research has become less focused on discovery and fundamental research.

There is risk in this shift in funding priorities. The fruits of fundamental research are often not immediately recognised but can become immensely important in a not-yet-realised future. For example, the Australian development of WiFi emerged from fundamental research in radioastronomy. A healthy science system needs the support of the full spectrum of research activities.

What does science in Australia look like?

Location

While CSIRO is Australia’s national science agency, contributing to 10 per cent of Australia’s published research, most of Australia’s research effort is conducted within our 42 universities. Of this, and based on expenditure, universities in the most populous states of New South Wales, Victoria and Queensland conduct over three-quarters of Australia’s research activities. Scientific research also takes place in Australian Government departments such as the Bureau of Meteorology and Geoscience Australia, in state government departments, and in a network of research institutes, which includes 57 medical research institutes.

Notably, if research is measured by expenditure rather than by amount of published research, the majority of Australian research is conducted in industry and private business, where outputs are not formally published—often to protect commercial advantage.

Outputs

New discoveries in science are most often shared in research papers. When compared with other OECD countries, Australia produced 3,047 publications per million population in 2017, which is well above the OECD average of 1,871. However, research outputs from some research institutions, particularly those based in industry, are not often published. Sometimes these institutions will instead file patents or develop commercial products. Collectively, these outputs directly feed into the broadening of our knowledge and understanding of the world or the advancement of products and services that support our lifestyles.

In addition to these direct outputs, the scientific endeavour in Australia also produces a highly skilled and adaptable workforce. Many of these people also volunteer their skills and expertise at community science outreach events, helping to build trust in science and inspire young people to study science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) subjects.

Australian universities also contribute directly to Australia’s economy. Education is Australia’s third-largest export, after iron ore and coal, and contributed over $28 billion to the economy in 2016–17. Prior to the COVID‑19 pandemic and travel restrictions, this made Australia the world’s third-largest provider of international education.

People

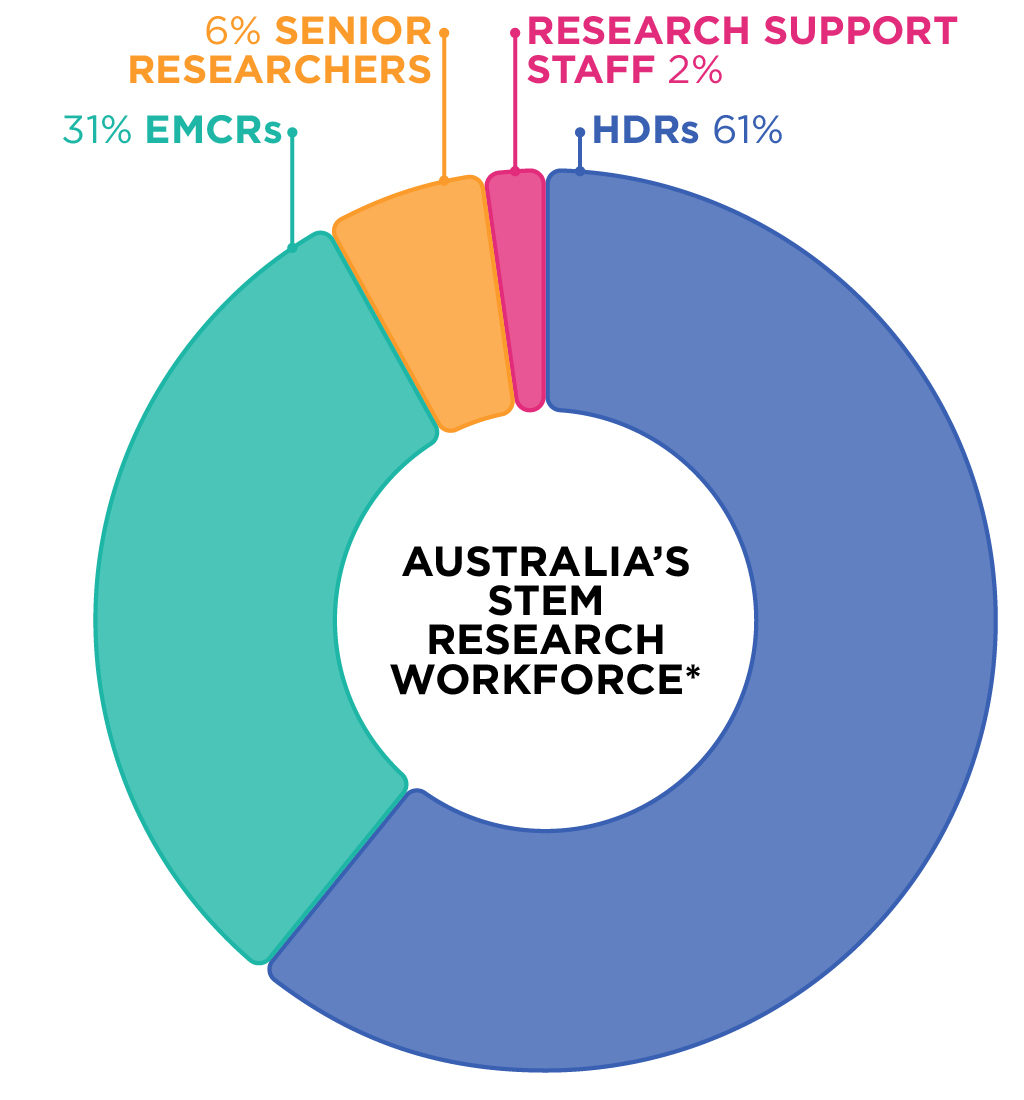

Australia’s research workforce is comprised of STEM-qualified professionals, including but not limited to postgraduate and higher degree by research (HDR) students, early- and mid-career researchers (EMCRs) and late-career or senior researchers.

In 2018, estimates^ indicate that there were more than 66,000 STEM-based researchers in Australia, with HDR students making up 61 per cent of this research workforce. Since 2001, the number of science HDR students has increased every year. In 2018 there were more than 40,500 STEM-based HDR students, half of whom were international students. STEM EMCRs make up 31 per cent of the research workforce, senior researchers 6 per cent and STEM research support staff make up 2 per cent.

In 2018 approximately 66 per cent of university staff were employed on a casual basis or on a fixed-term contract, compared to about half of all working Australians employed in permanent full-time positions.

In 2018, approximately 41 per cent of all STEM researchers were women. However, this ratio varies significantly between research disciplines. For example, in medical and health sciences, women comprised 52 per cent of researchers and in the physical sciences and engineering, they comprised just 19 per cent. The ratio also differs markedly for career stage, where 43 per cent of STEM EMCRs were women but only 22 per cent of STEM senior researchers were women.

Further adding to Australia’s research workforce is the contribution of non-salaried staff, estimated to account for 33 per cent of research outputs. These people include emeritus or visiting fellows, staff on exchange or secondment and conjoint and adjunct researchers.

Australia’s research workforce is strengthened through collaborations with international partners. Collaboration not only enables Australian-based researchers to share and exchange new knowledge and information, but also facilitates our access to crucial research infrastructure that is not available in Australia, such as satellites that collect Earth observation data. In turn, international researchers also share their expertise and can access our national research infrastructure.

Importantly, whether research projects occur within national boundaries or cross international borders, scientific research requires the collaborative effort of a team of researchers. The idea that single individuals are responsible for the leaps and bounds of scientific advancement is erroneous, but often it is just one or a few researchers within a much larger team who receive public credit.

Australians need science

Meeting global challenges that are becoming increasingly complex and far-reaching requires research expertise. The Department of Industry, Science, Energy and Resources highlighted that Australians depend on science and research to increase productivity, achieve sustainable economic growth, create jobs and improve national wellbeing.

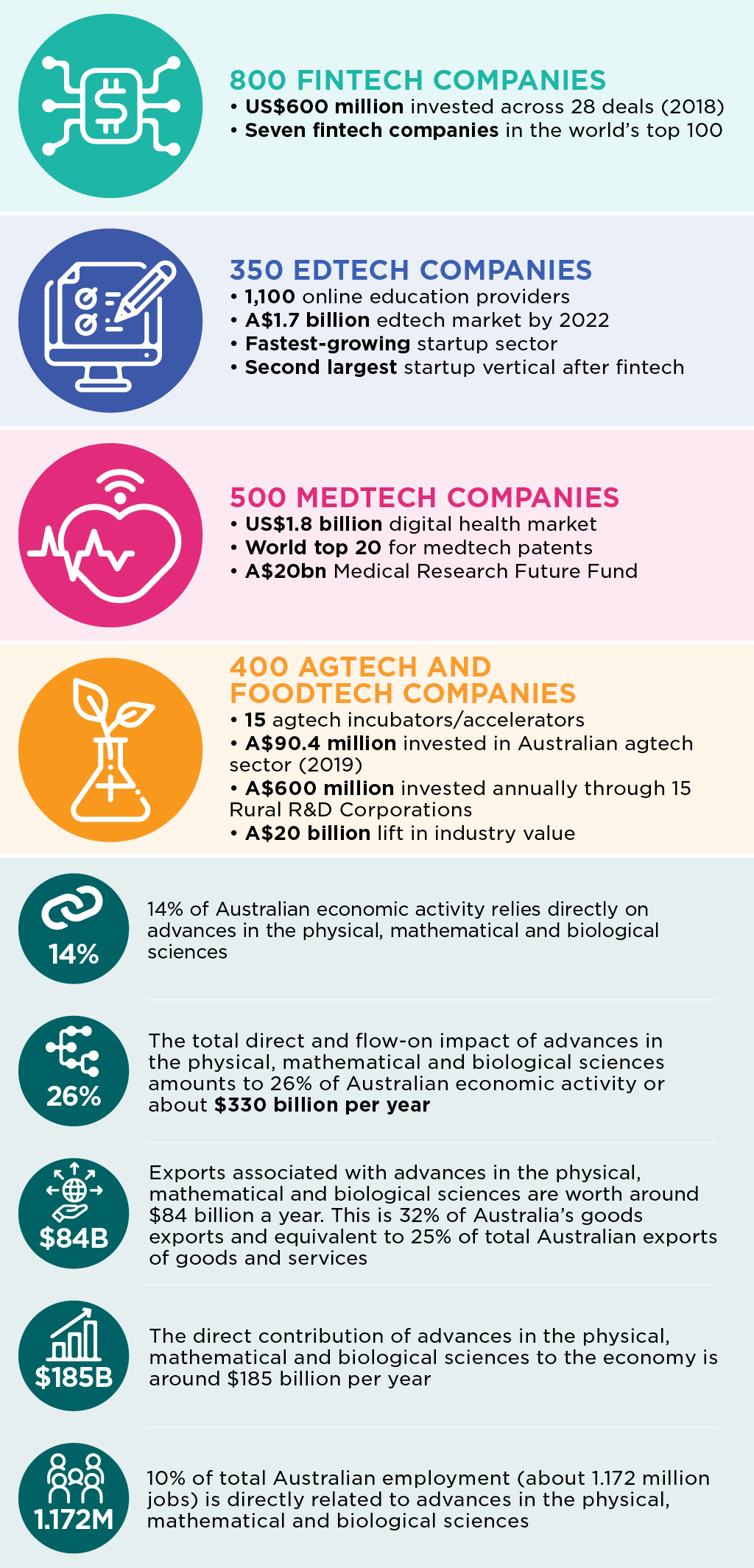

Science in Australia has supported our transition to a services-based economy. This transition has created 800 fintech companies, 500 medtech companies, 400 agtech and foodtech companies and 350 edtech companies. In a 2016 report by Australia’s Chief Scientist, more than a quarter of Australia’s economy can be attributed to advances in science. The report highlights that the direct contribution of advances in the physical, mathematical and biological sciences to the economy is $185 billion per year, which supports 1.2 million jobs.

Importantly, although international research collaboration is crucial for scientific advancement, local researchers must address challenges specific to Australia and its people. We cannot be complacent and rely on the efforts of others. Our international collaborators or other nations will not adequately handle questions and challenges in Australia’s interest, and we cannot wait to adapt the discoveries, innovations and technology produced by other countries to meet our own needs. The challenges Australia faces, such as water management in the Murray Darling Basin, the impact of climate change on the Great Barrier Reef, our agriculture sector or our biodiversity loss, will only be addressed by Australian researchers for Australians.

The future of Australian science

There is increasing demand in the public and private sectors for a highly skilled workforce. People with deep discipline-specific knowledge, sound research and analytical skills and the ability to be flexible and collaborate are required to address complex environmental, social and economic problems.

Even though there has been an increase in Australia’s STEM-qualified labour force, difficulties in navigating a challenging research culture in addition to insecure career prospects mean that Australia faces a ‘postdocalypse’. Australian-trained EMCRs seeking career stability are now looking at international positions or leaving their science careers entirely.

Australia’s National Science Statement notes that ‘governments and industry will increasingly look to scientific knowledge and skills to meet national and local needs in areas as varied as health care, defence, energy, transport, environmental management, food security and communications’.

Scientific knowledge and skills are vital to Australia’s future. Ensuring that the current and future generations of Australian researchers are adequately trained with expertise crucial to our national interest, and that they can access the infrastructure needed to conduct research, will support Australia’s economic competitiveness and the wellbeing of Australians. It will also ensure that Australia can contribute to the global scientific endeavour.

^ Estimates have been calculated using data pulled from:

- STEM-related FoR codes used in calculations include: 01 to 11 and 17

- HDR student data obtained from the Department of Education, Skills and Employment;

- Approximate number of EMCRs calculated based on: FTE staff at Level A to D in STEM-related two-digit FoR Codes in the 2018-19 ERA report,

- Senior Researchers = Level E of 2018-19 ERA report