The enormity of the Milky Way

We see the Milky Way every time we look up into the sky on a clear night, a collection of stars that forms the band of light the early astronomers likened to the colour of milk.

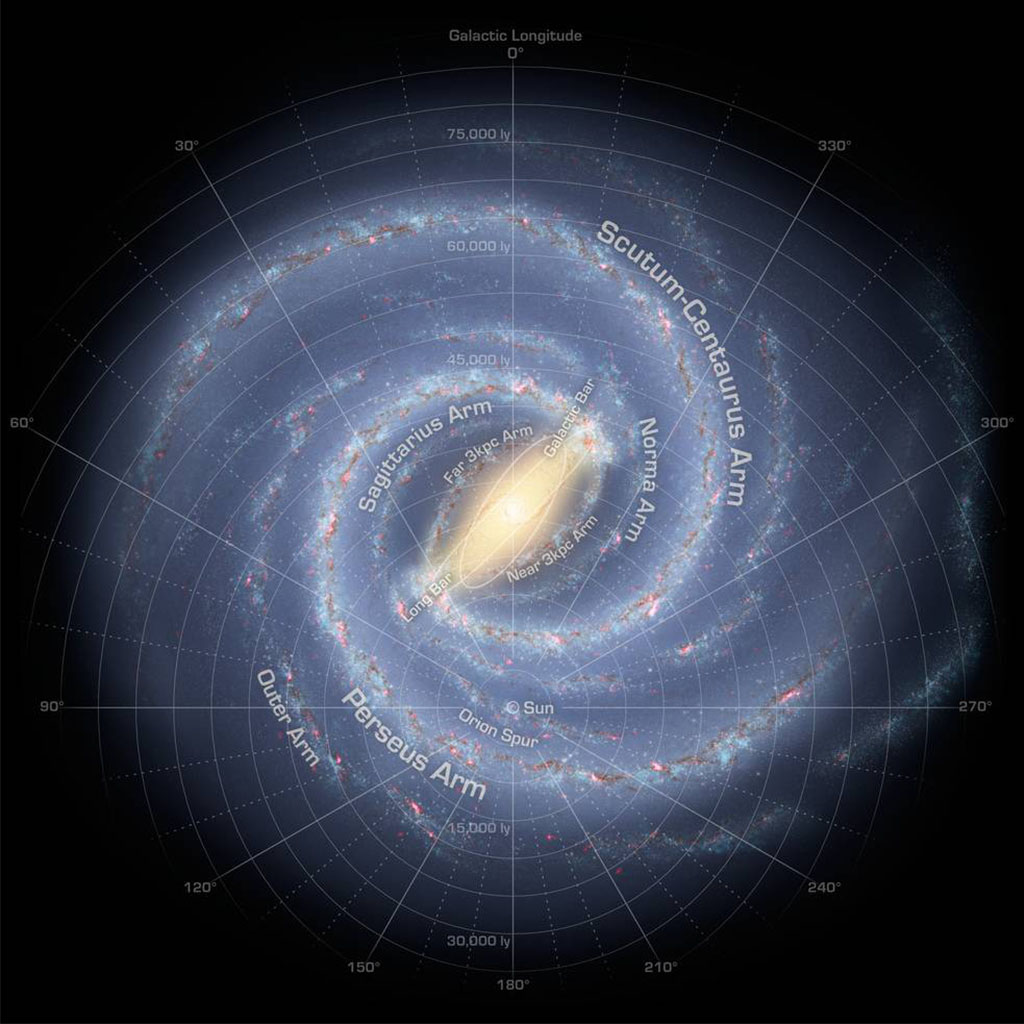

Galaxies are collections of stars, clustered together kind of like islands in a sea of space. Some galaxies are bigger than others, and they come in a number of different shapes. Our Milky Way is a barred spiral galaxy, which means that if we could see it from above (which we can’t because we’re in the middle of it!) we would see ‘arms’ spiralling around and around a central point, in a pinwheel shape.

The Milky Way has two major arms: the Perseus Arm and the Scutum-Centaurus Arm. There are also two minor arms, and two smaller ‘spurs’. Earth, our sun and the rest of our solar system is embedded within the Orion spur.

The total diameter of the Milky Way is between 100,000 to 150,000 light years (a light year is the distance light travels in one year, equal to 9.5 x 1012 kilometres) and it has a thickness of around 1000 light years. By contrast, the largest known galaxy, called IC 1101, is around 4–6 million light years in diameter.

While the Milky Way is no giant in terms of distance from one side of the galaxy to the other, with regard to mass, the Milky Way is not a bit player—our galaxy’s mass is around 600 billion times that of the sun.

And we’re certainly big compared to some of our nearest neighbours—the Large and Small Magellanic Clouds, two dwarf galaxies, are much smaller. You can see these with your eyes as two fuzzy patches in the night sky. The Large Magellanic Cloud is only around 14,000 light years across, and the Small Magellanic Cloud a measly 7,000 light years across. They are both less than one tenth the mass of the Milky Way. That said, the mass of the Large Magellanic Cloud is still around 10 billion times that of the sun, and the Small Magellanic Cloud is around 7 billion times as massive as the sun.