Pluto’s planetary predicament

Poor old Pluto. It never asked for all this drama, yet it has found itself at the centre of a storm of controversy ever since it was demoted from a ‘planet’ to a ‘dwarf planet’ back in 2006.

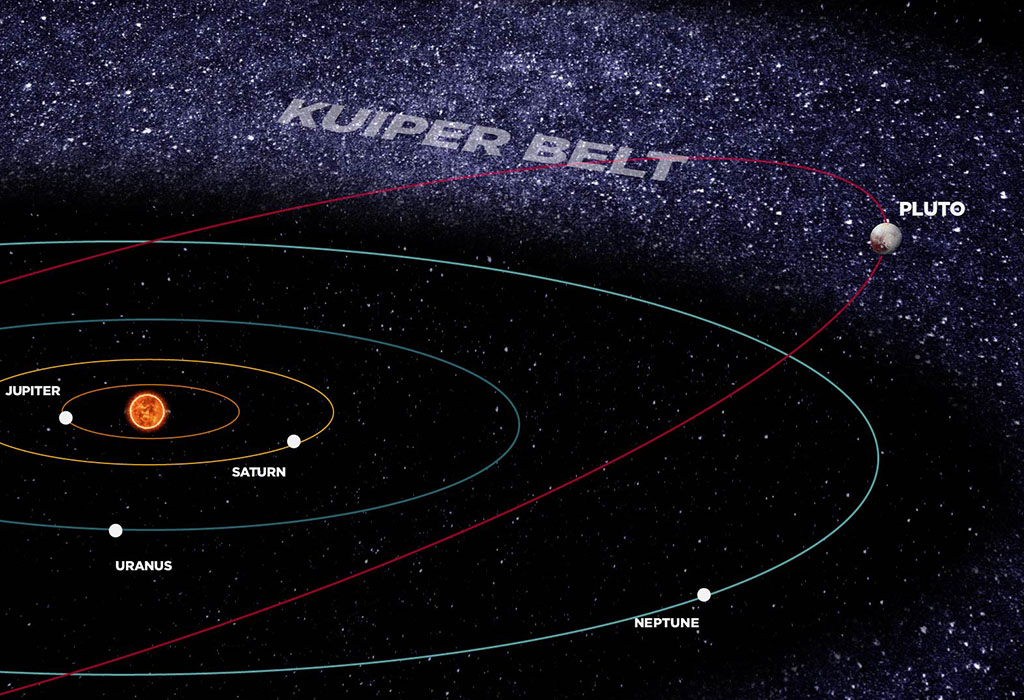

You may remember Pluto as the ninth planet in our solar system. It was the one furthest away from the Sun, with the slightly wonky-looking elliptical orbit and a peculiar relationship with one of its moons. Despite being the odd one out, though, it was still regarded as a legitimate member of the ‘planets’ family.

And then, after a controversial ruling from the International Astronomical Union (IAU) in 2006, Pluto got a new label: dwarf planet. It was a decision that led to the rewriting of textbooks and a lot of very heated debate.

The original decision

The whole discussion came to a head in 2005 when a team led by astronomer Mike Brown discovered a rocky world making its way around the Sun beyond Pluto’s orbit. It was roughly the same size as Pluto, but with greater mass, and was eventually named Eris.

But was Eris our solar system’s tenth planet? Or something else? Since 1992, scientists had been discovering and describing new worlds beyond Neptune at an ever-increasing rate, but were they all ‘planets’?

At the time, there was no official definition for the term ‘planet’. The IAU decided to rectify this by drawing up a short list of criteria for what a ‘planet’ could be and asking members to vote on the definition at the IAU General Assembly meeting in Prague in August 2006.

They also discussed plenty of other astronomy discoveries and voted on a few other resolutions (such as classifying asteroids, comets and a bunch of other not-planets as ‘small solar system bodies’), but the one that caused the biggest stir was Resolution 5A: Definition of ‘planet’.

By this new definition, a planet:

- Is in orbit around the Sun. This rules out our Moon, for example, or any other ‘natural satellite’ orbiting around another planet or celestial body.

- Has sufficient mass for its self-gravity to overcome rigid body forces so that it assumes a hydrostatic equilibrium (nearly round) shape. This is a bit of a mouthful, but it essentially means a planet needs to have its mass pulled into a nicely rounded shape by its own gravity. It doesn’t have to be a perfect sphere—even Earth has a bit of a bulge across its middle—but it rules out potato-shaped asteroids, for example.

- Has cleared the neighbourhood around its orbit. A planet needs to be massive enough to completely dominate its pathway around the Sun. Often this means knocking other objects out of its way, or drawing them closer towards itself—but at the end of the day, a planet needs to be the biggest boss of its celestial turf.

It’s this third part of the definition that sparked the most heated discussion, and the criterion that knocked Pluto from its planetary perch. Although Pluto orbits the Sun and is nice and round, it shares its orbit with a lot of other small, icy bodies in the Kuiper Belt, out beyond the orbit of Neptune. That was sufficient to reclassify Pluto as a dwarf planet.

The ongoing debate

A lot of people, ranging from primary school children to senior astronomers, were pretty emotional about the reclassification of Pluto. The state of New Mexico in the USA went so far as to pass legislature declaring that they didn’t care about what the IAU said, Pluto was still a planet, thank you very much. Even the chief of NASA weighed in on the debate as recently as 2019, declaring his steadfast support for Pluto’s planetary status (although his background is in politics, rather than science).

Some have argued that the IAU’s planet-defining criteria were declared too hastily and without enough consultation with planetary scientists. One such planetary scientist, Alan Stern, claimed that a better definition would take the geological and physical attributes of a planet (or not-planet) into account. The New Horizons mission, which flew by Pluto in 2015, showed that Pluto has mountains, avalanches, weather, an atmosphere (albeit a very thin one that’s expected to collapse), multiple moons and possibly an underground liquid ocean, proving that it’s far more complex than previously thought.

The notion of ‘clearing the neighbourhood’ has also been somewhat contentious. Even the Earth can’t make this claim, but no one has suggested demoting Earth to dwarf planet status. Some have tried to clarify what ‘clearing the orbit’ means, suggesting that a completely clear pathway was never the point of the definition; rather, being a dominant mass along that orbital path is the aim.

Does it matter?

But what’s in a name—or a definition—anyway?

Scientists need to have systematic ways of labelling and grouping things. We see this in biology, for example, where the rules of taxonomy govern how we name and organise living things, or in the rules for naming chemical compounds set out by IUPAC. These systems help researchers to understand the properties of what they study, how they all fit together, and how to communicate about them.

As the organisation responsible for giving official names to planets, the IAU needs to have official definitions for how to categorise different celestial bodies. Otherwise we could end up with hundreds of planets in our solar system, each with very different properties to each other, leading to confusion around how to study and describe them all.

There are plenty of places in our solar system that are worthy of scientific exploration that aren’t planets. As well as Pluto, four other dwarf planets have been named and described (Eris, Haumea, Makemake and Ceres—and possibly Hygiea, too), and some of Saturn’s and Jupiter’s moons have been considered some of the best candidates for harbouring life beyond Earth in our solar system.

Even though the debate around Pluto’s classification continues, Pluto is still Pluto: we have so much more to learn about this rich and complex world, which will continue to inspire and fascinate us long into the future.