Is there life on Saturn’s moons?

In September 2017, NASA’s spacecraft Cassini took its final plunge into Saturn’s atmosphere after an impressive 20 years in space. Prior to its heroic demise, the Cassini-Huygens mission was responsible for acquiring 635 gigabytes of data about Saturn and its moons, which contributed to over 4,000 published scientific papers.

Among other things, Cassini revealed Saturn’s moons to be unique worlds potentially capable of harbouring life. Two of them stood out from the others: Titan and Enceladus.

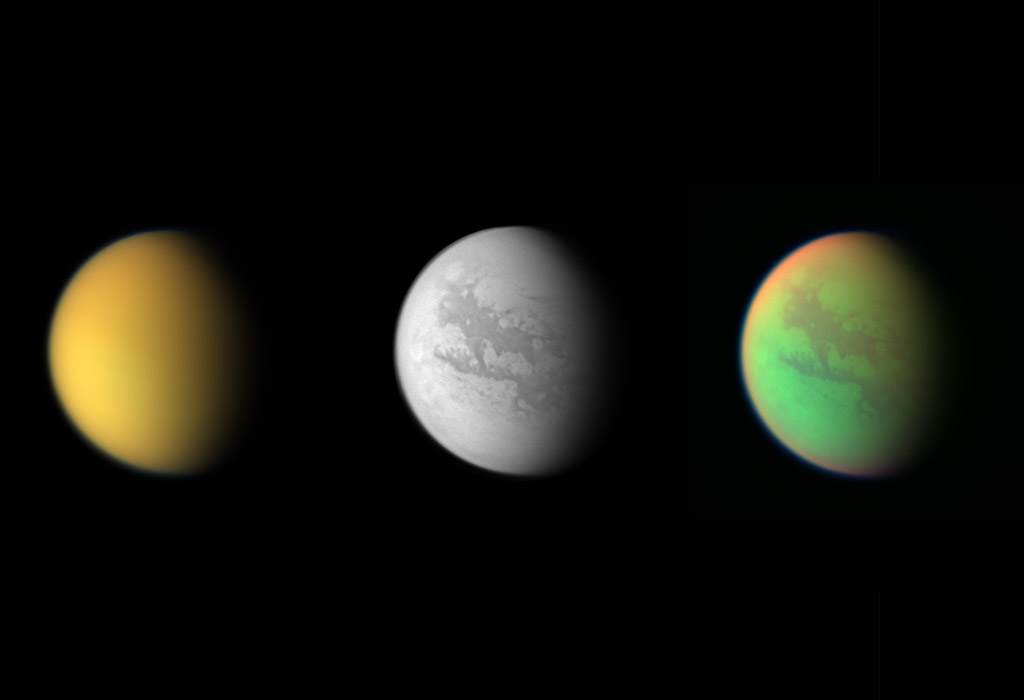

Titan

Titan is Saturn’s largest moon, and it’s a remarkable place. It has a thick atmosphere—even thicker than Earth’s. Its atmosphere is primarily composed of nitrogen and methane, and it’s chock-full of organic compounds—made when sunlight breaks down methane—which are thought to rain down on the surface.

It’s incredibly dynamic, with powerful winds and dust storms and ice volcanoes—and it’s even a little geologically spooky at times. For instance, the sand is weird: it has a tendency to bunch together, unlike the sands we know here on Earth that scatter with the slightest wind. It’s thought that electrostatic forces may be causing the sand particles to clump together, raising the possibility of building sandcastles that last for weeks at a time.

Titan is also very cold, with a surface temperature of around –180°C. There are rivers and lakes on the moon’s surface, but they’re not filled with water. They are thought to contain an oily mixture of methane and another hydrocarbon called ethane. NASA is thinking about building a submarine capable of exploring Titan’s murky hydrocarbon depths.

Going from our Earthly evidence we tend to think that water is an essential ingredient for life. But, really, all life needs is liquid in which the necessary chemicals can dissolve and interact with each other. What’s to say that that liquid can’t be a hydrocarbon? DNA, the blueprint for all life on Earth, isn’t soluble in methane, but perhaps a potential life form on Titan could be based on some other sort of chemical structure.

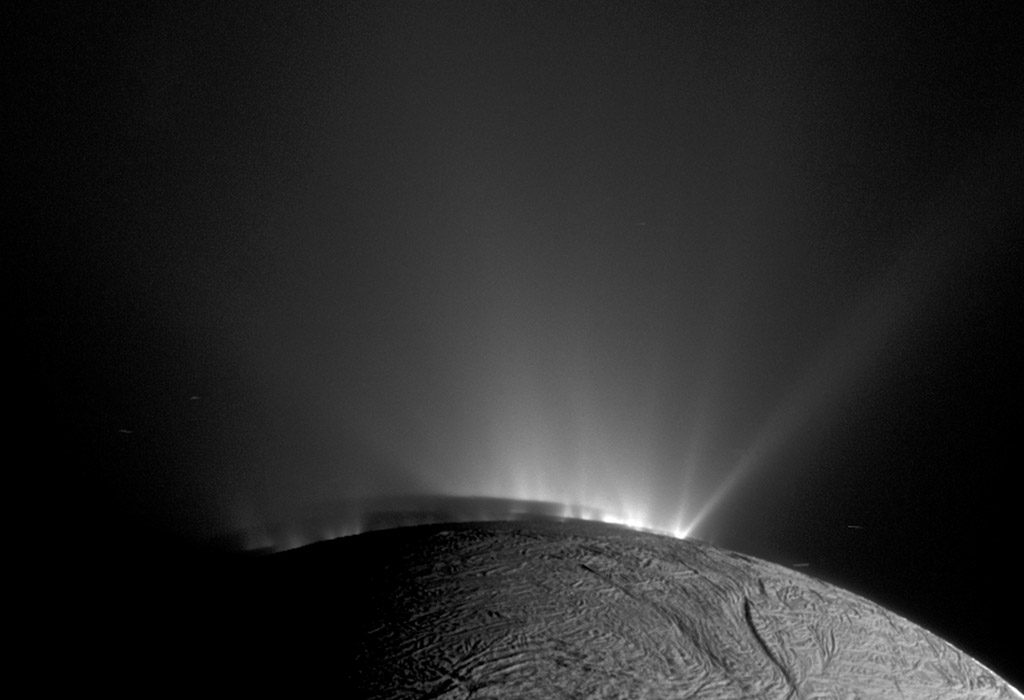

Enceladus

Enceladus is another cold, frozen moon, only around 500 kilometres in diameter. Like Jupiter’s moons Europa, Ganymede and Callisto, it’s thought to contain an underground (well, under-ice) ocean. Beneath a 30–40 kilometre-thick icy crust, the ocean is around 10 kilometres deep. Cracks and extensional features within the icy crust provide evidence that the moon is active. The activity is driven by tidal flexing, this time under the pull of Saturn’s gravity.

Also, like Europa, Enceladus has geysers of water erupting from its surface. Being much smaller in size than Europa means it has weaker gravity, and at least some of the water from Enceladus’ geyser escapes to space.

The water spouting from Enceladus’ south pole geysers has been sampled by the Cassini space probe and has been found to be salty and contain organic molecules, the basic ingredients for life. What’s more, those organic molecules are relatively complex, which is unusual beyond Earth. They likely originate from hydrothermal activity deep in Enceladus’s core, where they could then make their way into the moon’s oceans before bubbling up to the surface.

There’s no direct evidence of life just yet, but the conditions are promising. Researchers experimenting with methanogens (simple archaean species found living in ‘extreme’ conditions on Earth) found that they could survive in conditions similar to those thought to be present on Enceladus.

There’s a complex set of conditions needed to create and sustain life, and we’re yet to find somewhere that fits the bill or ticks all the boxes. Yet the prospect of ticking those boxes is exciting: who or what is actually out there?