AI and the robotics revolution

If Hollywood standards are anything to go by, the future is full of killer robots waging war against humanity. Most sci-fi plot lines have artificial intelligence systems running out of control, taking over the world and destroying our lives. The future looks bleak.

But is it? Robotics and artificial intelligence (AI) systems already help us with everything from vacuuming and grocery shopping to driving cars and booking appointments. Machines that can learn, make decisions and automate tasks are already part of our lives—the big question is, how do we make sure they’re helping society, rather than harming us?

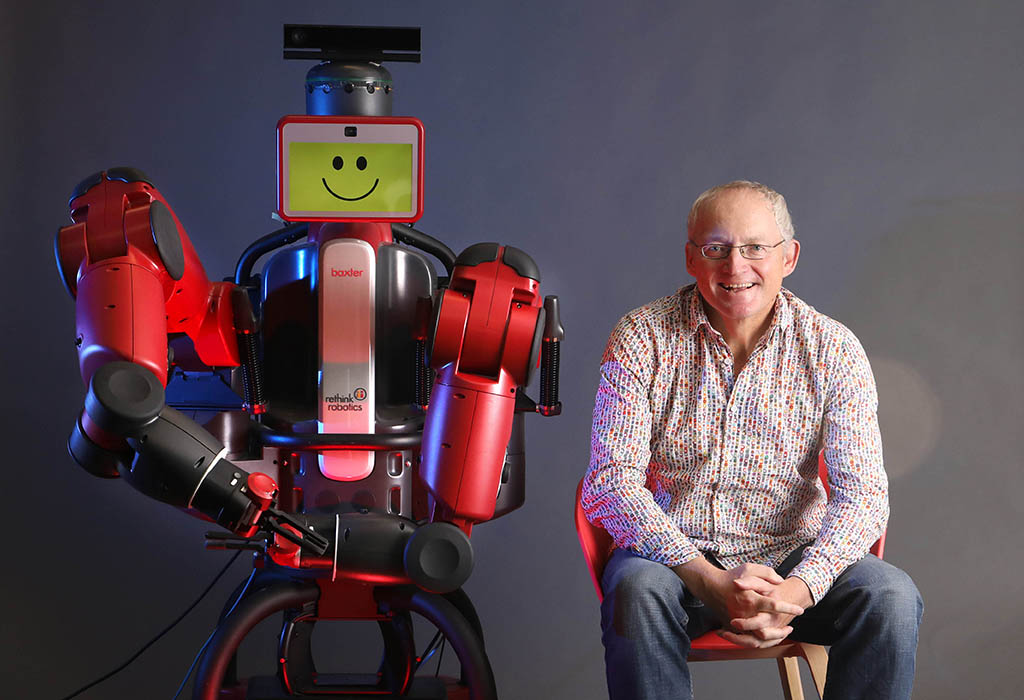

It’s these ethical conundrums that researchers like Professor Toby Walsh are working to answer. As we continue to develop machines with decision-making abilities that are comparable to those of a human mind, recognising and addressing these questions are more important than ever.

‘Technology like AI will change society. It’s already becoming part of our lives,’ says Walsh. ‘But society also gets to change technology. We need to work out how to make sure it improves the quality of everyone’s life.’

Walsh’s fascination with AI, robotics and technology was fuelled by a childhood spent reading science fiction by authors such as Isaac Asimov and Arthur C. Clarke. He has since built his career around artificial intelligence, trying to understand how computers can make decisions and act on them.

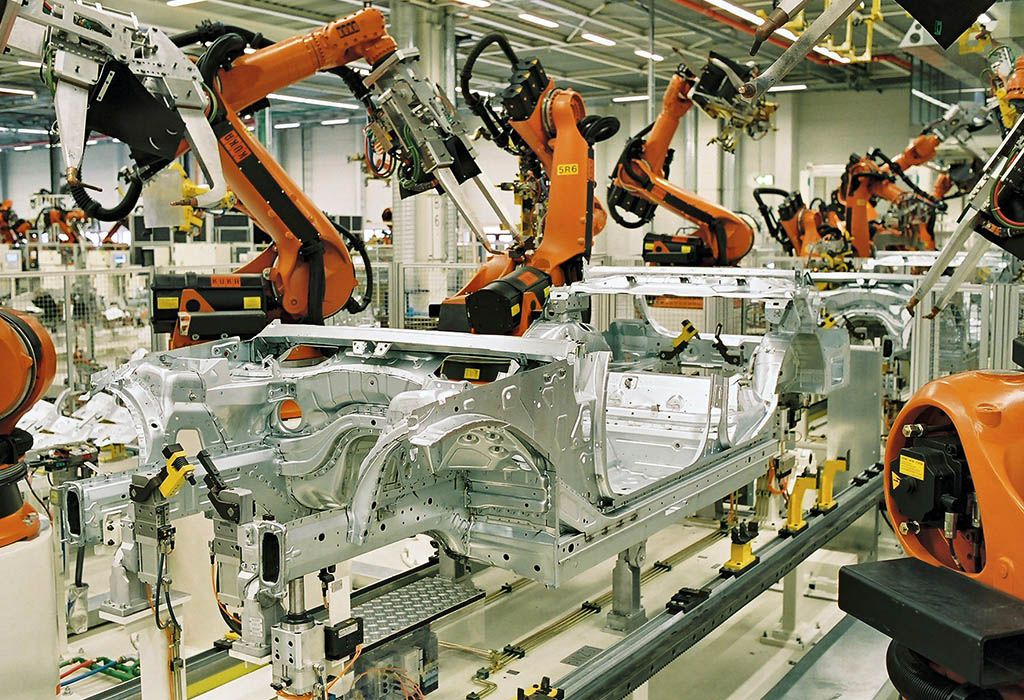

Machines have been helping us with our work for a while. In a series of technological revolutions, humans moved from mostly working in fields, to factories, to offices. We built machines to take over tasks that were physically demanding, tediously dull or downright dangerous. With each societal shift, the nature of work changed.

Historically, most of the machines we have built are very good at doing narrowly-defined, predictable work. Now, however, we’re developing intelligent machines that can learn and think a little like us. Sometimes, with the right training, they’re even better at making decisions than we are.

‘Humans are actually terrible at making decisions,’ Walsh says. ‘Behavioural psychology is full of examples of how humans are irrational in their decision-making. With the large data sets that computers can process, machines could be much better at it.'

Machines mostly learn through a testing process of repeated trial and error. Give a machine lots of data, ask it to answer a question, and then tell the machine whether it gave a correct answer. After repeating this process millions of times (and getting things wrong a lot of the time), the machine gradually gets better at giving correct answers, finding patterns in the data, and working out how to solve increasingly complex problems.

Machines can only learn based on the data they’re presented with—so what happens if there are problems with that data? We’ve already seen artificial intelligence systems that preference male over female candidates applying for technical jobs, or making a range of errors about people with dark skin tones, based on the biased data they were provided with.

‘We should think very carefully about what it is to be fair and what it means to make a good decision,’ says Walsh. ‘What does it mean mathematically for a computer program to be fair—not to be racist, ageist, or sexist? These are challenging research questions that we're now facing, as we hand these decisions to machines.

‘Those decisions might have impacts upon someone’s life: decide who gets a loan, who gets welfare, how much insurance we should pay, who goes to jail. We need to be careful about handing those decisions over to machines because those machines may capture the biases of society.’

That means there’s still plenty of work to do. We need to get better at knowing how to teach machines before giving them too much responsibility. Once we do, the benefits to society will be immense—and we can already see real-world examples of how AI is improving our lives.

Warehouse-dwelling robots don’t get sore feet, aching muscles or occupational injuries from picking, packing and sending deliveries from a warehouse. AI algorithms can speed up medical research by rapidly (and accurately) predicting the shapes that proteins will fold into, while other algorithms help us communicate by breaking down language barriers.

We’re watching the next technological revolution unfold. That means navigating a period of significant societal disruption as entire industries become taken over by machines—something that Walsh acknowledges we’ll need to manage carefully.

‘We need to work out, as a society, how to support people as they re-skill to keep ahead of machines,’ said Walsh. ‘We’re going to be using technologies in 30 years’ time that were invented in 20 years’ time. We’re going to have to do lifelong learning and pick up those skills as we go along.’

But the future isn’t as bleak as Hollywood might have us believe. Transitioning to the Age of AI doesn’t mean humanity will be left jobless and adrift. It just means the nature of work will change, just as it has done in revolutions past: probably for the better.

It’s a future that Walsh is looking forward to. ‘We should celebrate when robots take over jobs because those were dull, repetitive jobs that humans probably should never have been doing! We should celebrate now that we’ve got machines to do those things.’