How do 3D printers actually work?

3D printers are the talk of the town—it seems there’s almost nothing they can’t do. But if you’re still a bit confused about how they actually work, this quick explainer will help you join the conversation.

Traditional printers—like the type you have in your home or office—work in two dimensions. That is, they are able to print text or images on a flat surface, usually paper, using the x (horizontal) and y (vertical) dimensions. 3D printers add another dimension—depth (z). They can move up and down, left and right, and backwards and forwards and, instead of delivering ink on paper, they distribute different materials—ranging from polymers (including plastics), metal, ceramics, even chocolate—to ‘print’ an item layer by layer in a process that is known as additive manufacturing.

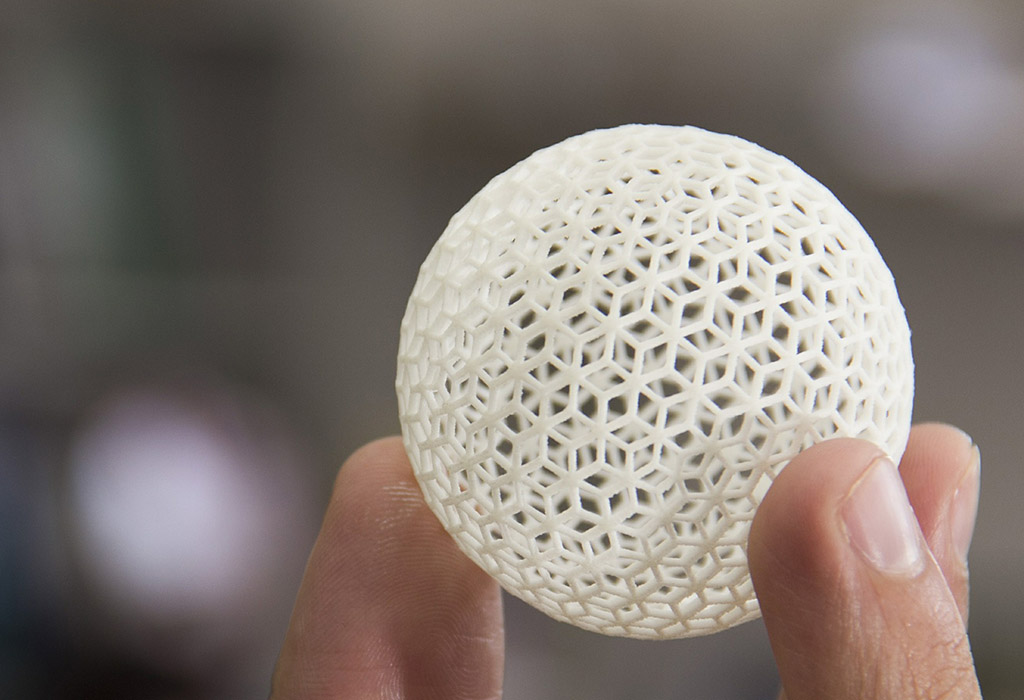

To create a 3D object, you first need a blueprint—that is, a digital file created using modelling software. Once created, the computer-generated model is sent to the printer. Your chosen material (such as plastic) is loaded into the device, ready to be heated to allow it to easily flow from the printer nozzle. As it reads the blueprint, the printer head moves up and down, side to side and forward and back, depositing successive layers of the chosen material to build up your final product. As each layer is printed it transforms into a solid form, either by cooling, chemical reaction (often induced by light), or by the mixing of two different solutions delivered by the printer head. New layers adhere to the previous one to create a stable, cohesive item. Almost any shape can be created in this way, including moving parts and complex layers.

A wide range of items are already being created using 3D printers, including jewellery, clothing, toys, prototypes, camera cases, high-end manufactured items and even human tissue.

It’s a technology that holds a lot of potential, and we’re only just beginning to see where it may lead us.