Blood types: the not so bleeding obvious

Expert reviewers

Essentials

- Blood types are determined by the presence or absence of particular antigens on the surface of red blood cells.

- There are eight main blood types: A positive, A negative, B positive, B negative, AB positive, AB negative, O positive and O negative.

- The positive and negative refers to your Rh type (once called Rhesus).

- In addition to ABO and Rh, there are 34 other recognised blood types, called blood group systems.

- Introducing the wrong type of blood into a person’s body can trigger a potentially dangerous, even fatal, immune response.

Accentuate the positive, eliminate the negative … that’s the song I start humming whenever I’m asked for my blood type. That’s because mine is B positive—which is kind of cool, really. Life affirming, in a pop-psychology kind of way. But, apart from the warm fuzzy, what does this actually mean?

Like most people, I know that some blood types are more common, or rarer, than others. I know that giving blood is a really good thing to do, and that getting the wrong type of blood in a transfusion is bad news. But when it comes to the nitty gritty, things get a bit hazier. Like, what makes my B-type blood different from your O-type blood? Is my type of blood special or run of the mill? And what would happen if I needed a transfusion and got the wrong kind of blood?

What makes different blood types different?

When it comes to what blood type (also known as blood group) you have, it’s all about the antigens. Antigens are various kinds of sugars and proteins on the surface of our cells, including our blood cells. Which antigens you have (or don’t have) on your red blood cells determines your blood type. Antigens are genetically determined—in other words, your blood type is inherited from a combination of your parents’ genes.

The eight main blood types

Altogether there are eight main blood types. You probably already knew that. But, before we get much further, let’s do a quick refresher.

The main blood types are:

- A positive

- A negative

- B positive

- B negative

- AB positive

- AB negative

- O positive

- O negative

A, B, AB or O?

So, what does this all mean?

Let’s break down my B positive blood type. Leaving aside the negative or positive part for a moment, what’s the significance of the letters A, B and O?

Whether your blood type is A, B, AB or O depends on whether you have, or don’t have, certain antigens (named A and B) on your red cells.

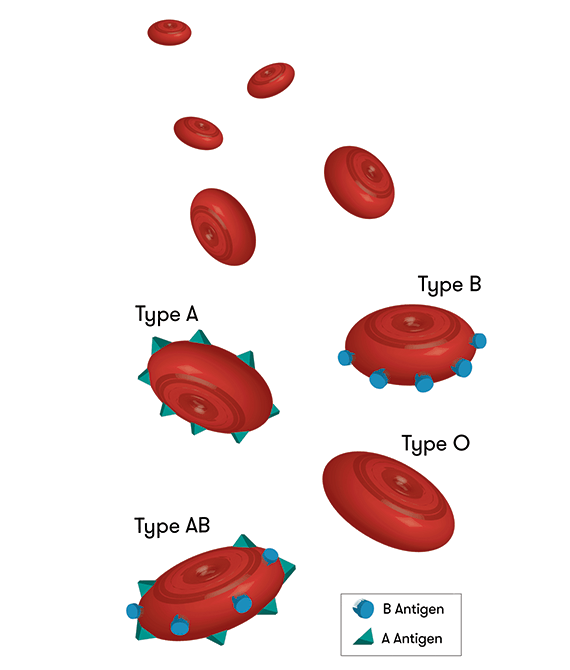

Your blood type is determined by the presence or absence of certain antigens on the surface of your red blood cells.

The presence or absence of A or B antigens gives us four main blood types:

• A type blood has only A antigens on red blood cells

• B type blood has only B antigens on red blood cells

• AB has both A and B antigens on red blood cells

• O has neither A or B antigens on red blood cells.

The flipside of having these particular antigens is the production of particular antibodies in your blood’s

plasma

GLOSSARY

plasmathe fluid portion of the blood, in which the blood cells are suspended

. These are produced in the first few years of your life in response to food, bacteria and viruses which you encounter. Antibodies are specialised immune proteins that are produced based on the antigens that are not present on your red blood cells. For example, if you have A antigens, you will develop only anti-B antibodies. So:

• A type blood has anti-B antibody in the plasma

• B type blood has anti-A antibody in the plasma

• AB has neither A or B antibody in the plasma

• O has both A and B antibody in the plasma.

What if you get the wrong type?

All this means that it’s really important that, if you happen to need a blood transfusion, you get the right type. That’s because if an antigen is introduced into your body which it doesn’t already have, rather than welcoming it with open arms, your system will identify it as an intruder. Alarm bells will start ringing (figuratively speaking), your immune system will go into attack mode, and antibodies will be produced to fight off the unfamiliar visitors.

Say, my stepdad, who has O-type blood, needed a blood transfusion. What would happen if he received my B type blood? Having O type blood, remember, means that he has no A or B antigens on the surface of his red blood cells. If my cells, with their B antigens, were introduced into his body, his immune system would identify them as foreign, producing antibodies to provide immunity against them.

Antibodies attack by binding to the foreign antigens, making the red blood cells clump together. If only small amounts of my blood were introduced into my stepdad’s system, this wouldn’t necessarily be a problem, as the rejected blood would be filtered out by his kidneys. But if he needed a larger-scale transfusion, his kidneys might not be able to cope. The result could be kidney failure and, potentially, death.

What about if the situation is reversed? Could my stepdad donate his blood to me? Because his O type blood doesn’t have any A or B antigens, it could be safely introduced into my body—it has no unfamiliar antigens for my system to identify as intruders. In fact, because it has no A or B antigens at all, O (negative) blood can be donated to anyone, regardless of blood type. This is why it’s known as the ‘universal donor’.

Before blood types were discovered in 1900 by the Austrian scientist Karl Landsteiner (for which he was later awarded the Nobel Prize), early attempts at blood transfusions, often using incompatible blood, frequently ended in disaster. (Fun fact: the first attempt at a blood transfusion was probably in the 1600s, when an English physician infused a wounded soldier with sheep’s blood. Later transfusion experiments used milk, water and even oil as blood substitutes!)

Who could safely receive my blood?

Select a blood type from the dropdown menu to find out who it could be donated to.

Plasma needs to be compatible, too

As you’ll know if you’ve ever looked into donating blood, it’s not just whole blood that can be donated— platelets GLOSSARY plateletscell fragments which interact with clotting agents to prevent or stop blood loss and plasma from donors are also used for various medical treatments.

Your blood type is important not only when it comes to donations of red cells, but also when we’re talking about donations of plasma. As we’ve seen, plasma contains certain antibodies depending on your blood type. So, while my stepdad, with his O (negative) type blood, can donate red blood cells to anyone, this isn’t the case for his plasma. Say he wants to donate plasma to me, a B-typer. Having 0 type blood means he has no A or B antigens on his red blood cells—and that he has anti-A and anti-B antibodies in his plasma. If he donated plasma to me, the anti-B antibodies in his plasma would attack my red cells. No plasma for me, thanks!

Positive or negative?

That’s the blood alphabet taken care of. I’m B type blood because I have B antigens on my red blood cells. Simple.

But what about the positive (or negative) bit? Why (and I’m not talking happy thoughts here) B positive?

Like A, B and O, the positive or negative component of a person’s blood type refers to a molecule which is either present or absent on the surface of their red blood cells. In this case, it’s an antigen in a blood group system called the Rh (originally called Rhesus) system. The Rh blood group system includes around 50 different red blood cell antigens, but the most important one is a protein called D. If you have the D protein on your red blood cells, you’re Rh positive. If you don’t have it, you’re Rh negative. In Australia, most people are (like me) Rh positive—that is, we have the D protein on the surface of our red blood cells.

(A side point here. Even though people talk about being ‘Rh negative’ or ‘Rh positive’, Rh type actually refers to the presence or absence of the RhD antigen in particular, not of Rh antigens generally. The absence of any Rh antigens, first discovered in an Indigenous Australian, is a different kettle of fish. It’s known as Rhnull and is extremely rare.)

Although there are lots of other Rh antigens, RhD is the most significant because it’s most likely of the Rh antigens to produce an immune response. This has implications for people receiving a blood transfusion, and also in pregnancy (as we’ll see below). Because an Rh negative person’s blood cells don’t have the D antigen, any D antigens introduced into their body may be identified as intruders, and targeted for destruction. For this reason, people with Rh negative blood type shouldn’t be given Rh positive blood.

Rh negative blood in pregnancy

It’s not unheard of for pregnant women to joke about the alien growing inside them, ready to burst out Sigourney-Weaver style. But when your body really does identify your unborn baby as a dangerous intruder, it’s far from a laughing matter.

This is what can happen when mothers and babies have incompatible blood types—that is, when a mother’s blood type is Rh negative, but her unborn child’s is Rh positive. It can become a problem if the baby’s blood enters the mother’s bloodstream—for instance, during childbirth. In a mother with Rh negative blood, the baby’s D antigens are identified as foreign, with the mother’s body producing antibodies against them. This isn’t usually a problem for the first baby, because the mother’s exposure to the first baby most frequently occurs at childbirth, but it can be a problem for all later pregnancies wherever the subsequent baby is Rh positive.If antibodies produced by the mother attack the unborn baby’s red blood cells, the unborn baby’s destroyed or damaged red blood cells may not be able to carry oxygen around their body. This could result in miscarriage or stillbirth. If the baby is born alive, they may have jaundice (caused by a chemical called bilirubin made by the baby’s liver as it breaks down the damaged red blood cells) and anaemia.

To help prevent this, Rh negative mothers in Australia receive a vaccine during pregnancy or shortly after birth which helps stop their immune system from making anti-D antibodies.

The 34 other blood types

A, B, AB or O can each also be Rh positive or negative, resulting in the eight main blood types. Now that we’re all comfortable with that, it’s time to throw a spanner in the works.

That’s because, while we’ve only looked so far at antigens in the ABO and Rh systems, there are actually hundreds of different antigens across more than 36 blood group systems that may be present on our red blood cells. For example, you may have AB blood in the ABO blood group system, be Rh positive in the Rh system, as well as being K positive in the Kell system, and so on. A complete blood type would actually list the full set of substances on the surface of your red blood cells. The names are often represented by initials looking something like this: Fy a/b, K/k, Jka/b, Lua/b, MN,S/s and so on.

You have a ‘rare’ blood type if your blood is missing an antigen which is common to most people, or if it has an antigen which most people don’t have. Say your blood lacks an antigen which is present on the red cells of the majority of the population. If you receive a transfusion of ‘ordinary’ blood which has that common antigen, it will be recognised as foreign, triggering an immune response with potentially catastrophic results. An example is the Jk system, where most people have Jka and/or Jkb types, but some people lack a and b and are a rare Jka–b– type. Indeed, many previously unknown antigens were discovered when blood which was previously thought to be compatible triggered an immune response in the patient when transfused. Conversely, if your blood has a rare antigen and is introduced into the body of a patient without it (as in the case of SARA, see below) it will be recognised as foreign.

Interestingly, for reasons which aren’t well understood by scientists, not all ‘foreign’ antigens are equally likely to be targeted for destruction by antibodies. So, although there are 36 recognised blood group systems in total, there are only certain types that doctors and patients need to be careful about when it comes to blood transfusions. ABO antibodies, for example, are pretty much always clinically significant. Other blood groups which are likely to cause transfusion reactions include the blood types MNS, Kell, Kid and Duffy.

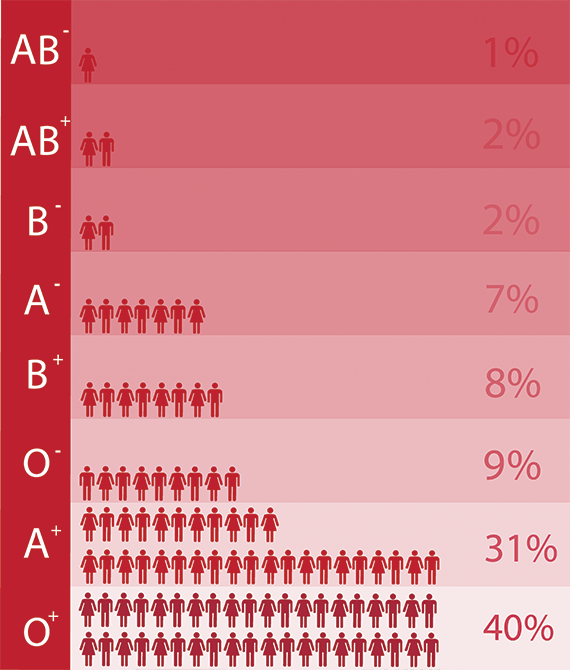

So now I know. Being B positive means that I have B antigens and RhD antigens on my red blood cells—as well as a whole load of other antigens. It means I have anti-A antibodies in my plasma—so, should I ever need a blood transfusion, I shouldn’t receive A or AB blood. It also turns out that, while my B positive blood isn’t the rarest type in Australia, it’s not the most common either. Guess it’s about time I got cracking and made an appointment with my local blood donation centre.

This graph shows the breakdown of different blood types in Australia. AB negative is the rarest type, and 0 positive is the most common.