by Charles Strebor

by Charles StreborWith its iconic reference to ‘droughts and flooding rains’, Dorothea Mackellar’s 1904 poem My Country highlights the large natural variations that occur in Australia’s climate, leading to extremes that can frequently cause substantial economic and environmental disruption. These variations have existed for many thousands of years, and indeed past floods and droughts in many regions have likely been larger than those recorded since the early 20th century. This high variability poses great challenges for recording and analysing changes in climate extremes not just in Australia, but the world over. Nevertheless, some changes in Australia’s climate extremes stand out from that background variability.

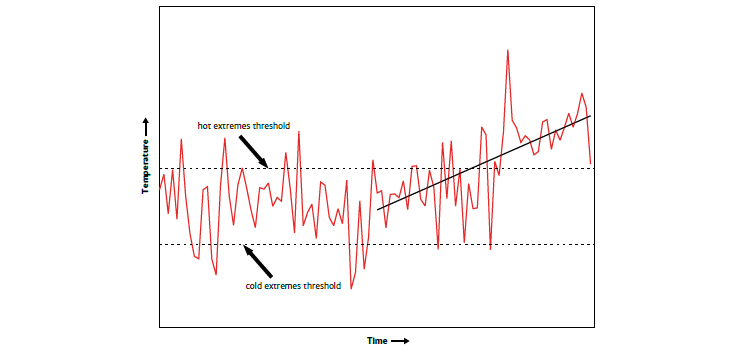

In a warming climate, extremely cold days occur less often and very hot days occur more often (Figure 5.1). These changes have already been observed. For example, in recent decades, hot days and nights have become more frequent, more intense and longer lasting in tandem with decreases in cold days and nights for most regions of the globe. Since records began, the frequency, duration and intensity of heatwaves have increased over large parts of Australia, with trends accelerating since 1970.

Because a warmer atmosphere contains more moisture, rainfall extremes are also expected to become more frequent and intense as global average temperatures increase. This is already being observed globally: heavy rainfall events over most land areas have become more frequent and intense in recent decades, although these trends have varied notably between regions and seasons. In southern Australia, for example, the frequency of heavy rainfall has decreased in some seasons. While there is no clear trend in drought occurrence globally, indications are that droughts have increased in some regions (such as southwest Australia) and decreased in others (such as northwest Australia) since the middle of the 20th century.

For other extreme weather events such as tropical cyclones, there are not yet sufficient good quality observational data to make conclusive statements about past long-term trends. However, as the climate continues to warm, intensification of rainfall from tropical cyclones is expected.

Recent scientific advances now allow us to begin ascribing changes in the climate system to a set of underlying natural and human causes. For example, it is now possible to estimate the contribution of human-induced global warming to the probabilities of some kinds of extreme events. There is a discernible human influence in the observed increases in extremely hot days and heatwaves. While the record high temperatures of the 2012/2013 Australian summer could have occurred naturally, they were substantially more likely to occur because of human influences on climate. By contrast, the large natural variability of other extremes, such as rainfall or tropical cyclones, means that there is still much less confidence in how these are being affected by human influences.

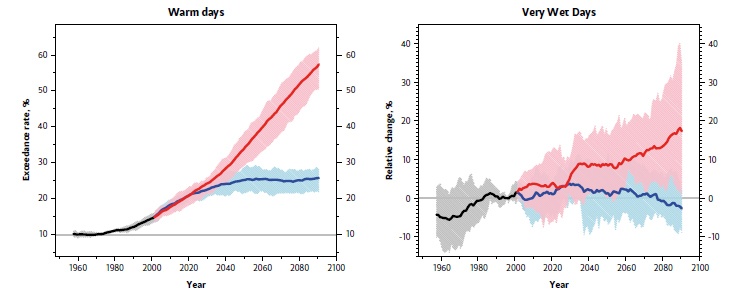

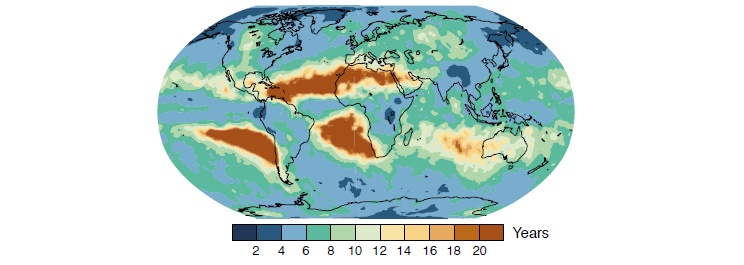

As the climate continues to warm in response to further greenhouse gas emissions, high temperature extremes will become hotter and cold extremes will become less cold. The rate of change of temperature extremes in Australia will depend on future emission levels: higher emissions will cause progressively more frequent high extreme temperatures (Figure 5.2 left). Climate model projections also suggest (though with considerable uncertainty) that in the next several decades, heavy rainfall events in Australia will tend to increase under a high emissions pathway (Figure 5.2 right). Across the globe, projections point broadly to an intensification of the wettest days and a reduction in the return time of the most extreme events (Figure 5.3), although there is much regional variation in these trends. For Australia, a warmer future will likely mean that extreme precipitation is more intense and more frequent, interspersed with longer dry spells, likewise with substantial regional variability.

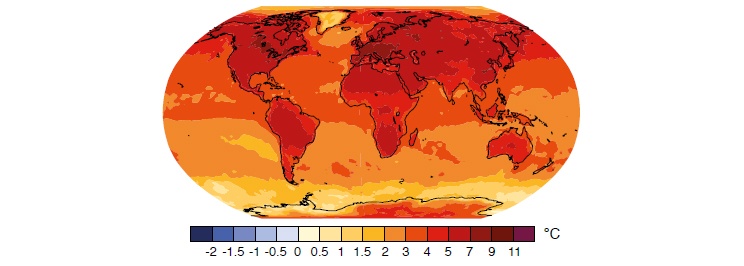

In many continents, including Australia, a high temperature event expected once in 20 years at the end of the 21st century is likely to be over 4°C hotter than it is today (Figure 5.4). Furthermore, what we experience as a one-in-20-year temperature today would become an annual or one-in-two-year event by the end of the 21st century in many regions.

Future changes in other extreme weather events are less certain. Evidence suggests there will be fewer tropical cyclones, but that the strongest cyclones will produce heavier rainfall than they do currently.

© 2025 Australian Academy of Science