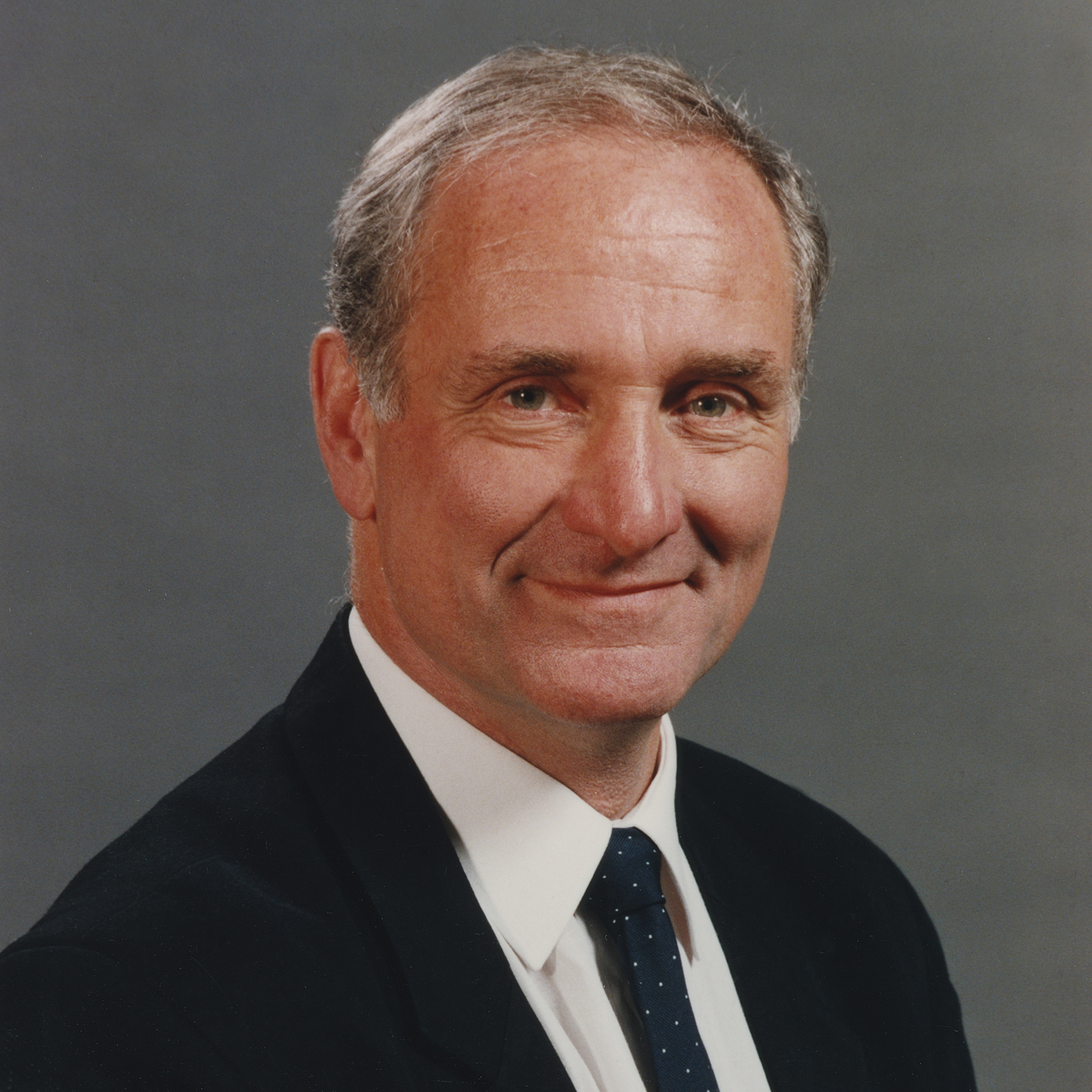

Professor Robyn Williams is perhaps the leading science journalist in Australia. As Executive Producer of the ABC’s Science Unit and presenter of The Science Show, one of the longest-running programs on Australian radio, Williams has made a significant contribution to the public understanding of science. In 1993 Williams became the first journalist elected as a Fellow of the Australian Academy of Science.

In this conversation with Dr Elizabeth Finkel, Williams recalls a stellar career against the backdrop of a childhood in post-war Europe and discusses what drew him to science, the arts and science broadcasting. He admits to graduating with a Bachelor of Science (Honours) in England despite spending as much time acting as studying. He talks of moving to Australia twice – first as a ten-pound pom inspired by an Australian friend and advertisements for migration on London public transport, then as a new graduate who successfully argued his way into a job in the ABC’s Science Unit in 1972.

Professor Williams recalls the early days of the Science Unit. A broadcast division whose creation was greatly influenced by Academy Fellows like Frank Macfarlane Burnet, Marc Oliphant, and John Eccles, whose return to home after World War II was crucial in Australia establishing and communicating a scientific tradition of its own, independent of Europe and America.

Williams also covers the beginnings of The Science Show, developing new programs for broadcast and the highs, lows, and major stories of his fifty years at the ABC. He talks about what has changed over the course of his career and what hasn’t, his hopes for the future, his appreciation for the long shadow of history and what inspires him about scientists today.

Edited transcript (262 KB - PDB)

Robyn, you're on the other end of things now. I get to interview you, but I'll be kind.

Robyn, more than three decades ago, the National Trust voted you a living treasure and the Sydney Observatory even named a star after you. What was true more than three decades ago is immeasurably more so today. Your consistently high rating Science Show is approaching its 50th birthday. That's five decades of observing science and society in your inimitable way from the perspective of every person. Let me just do a little overview of the terrain I want to cover.

First of all, I'd like to hear your reflections on nearly five decades at the helm of the Science Show, not so much filter feeding as drinking from the fire hose of sciences that happens. And yet, Robyn, all your stellar success, having a star named after you and being voted a national treasure has been against the relentless backdrop of financial starvation, unhelpful management, harassment by governments of all persuasions. Clearly, these pressures have evolved an agile survivor.

I'd also like to hear your reflections on that in this interview and really, to hear about what has driven you in this epic. From doing my homework, which mostly has involved reading your glorious books, where I've discovered a whole different Robyn Williams, because when you're doing your radio programs, the spotlight is on someone else, but you take the spotlight in your books, and I've discovered a whole different person than the one I thought I knew. I just love your books, and for whoever listens, get a hold of Robyn's books.

They are rye, irreverent, and panoramic over decades of science, passionate sketches of some of the wonderful, wonderful people you've met and wonderfully colourful terms of phrase. Some of which were quite new to me like sparrow fart. I've learned that you don't just have a passion for science as the stairway to progress, but about public broadcasting itself as the vehicle for enlightening the masses, it's been your abiding passion. That's the territory we want to cover, and I'll do my best to lead you through it. Everybody has to have their origin story told and so I know a big part of you is your frugality, your eclecticism, and your sense of public good.

So, tell me a bit about your beginnings and where these things emerged?

My beginnings were unpredictable and I got used to moving around a lot. I worked out that I'd been to something like seven junior schools before I was 8-years old and by the time I was seven, we'd moved to Austria in Central Europe and of course, that was 1950, which is only five years after World War II had finished. I was used to having a family that was moving around. I was actually born in High Wycombe because we'd moved out of London because of the Blitz and so, I was in this place which I've heard of. I've never been back.

Although when I go to Oxford on the bus, I look over the freeway and there it is sitting there and think - I must go back one day, but we were there because of Hitler. It's rather strange to remember that when I was born, Hitler had 14 months still to go. Anyway, there we were, lots of different schools and therefore lots of different friends, and my father's first language was Welsh. My mother came from Central Europe, and she had a very confusing family, which had lots of brothers, all with different surnames. My mother's surname was Davis.

There was Uncle Izzy who was Michael Lofsky. There was a Jacobs, there was a ... On it went. I couldn't quite work out what was going on until I suddenly realized that if you came from Central Europe and you had some Jewish around, you change your surname to adapt to the circumstances where your strange name wouldn't be weird. I couldn't work out. Was I Welsh? Was I Jewish? Was I European? And then suddenly, after all those different schools, I was in Austria and put in a junior school.

What took you to Austria?

Well, my father had moved there. My father went to Austria in, I think, late '49 because he had been a coal miner in South Wales. He was actually a Welshman from Central Casting. He was handsome. He spoke fluent Welsh. He played rugby. He was left-wing. He not only went down the pit when he was 14, but he came up and did higher mathematics and passed his exams and became a bloody engineer when he was hardly 18 or something. And walked up to the coal miners, the owners and said, "Your mine is dangerous," where upon they promptly sacked him.

He was an unemployed Welshman from Central Casting, which meant he went to become a bus conductor in London and he met my mother. I found out many, many years later when he died, when I was 18, that he never married her. So, there's all that uncertainty around the place. He went to Austria. My mother followed with ... I had a younger brother at that stage, and we moved into a place which was so horrifying on the way from the airport that I burst into tears looking at the rubble.

I'm reminded, of course, of Ukraine looking around like that at all the destruction. But we were well off. Instead of being penniless, we were suddenly well off and we had a couple of servants, and we were surrounded by people from all sorts of nations. I didn't notice nationality, particularly. I thought the world was full of a variety of people. I was put in a school, a volksschule, a folk school, a primary school where nobody spoke English and I spoke no German. I, obviously, had to learn German very quickly, which I did in a couple of months.

I'm giving you a picture of having to adapt to changing circumstances, different people, going out there and seeing extraordinary things. The characteristic that you describe of my being in the ABC, actually. I've been in the ABC now for 50 years, this particular year, two months ago. February 2022 was the 50th anniversary of my walking up the street. Yet from that stability, from that constancy, I've tried to have a huge variety of experience associated with other organizations, but always culture and science being my abiding interest. Because the world is so interesting.

Yes. Your father got a job in Vienna as an engineer, is that what it was? I see, and you were well off?

No. He was more or less a journalist. That was his alibi. That's what he put on the form, and he was also head of a union, in fact, two unions. One, of course, was the mining union because he was protesting so much about what happened to him early on and of course, the 1920s were full of minor strikes and God knows what else. He was also, for reasons I can't quite explain because everyone's dead, so I can't ask them, he was also a senior person in the scientific association.

He had those jobs with an organization called the WFDU, the World Federation of Trade Unions, which was situated in a palace in the middle of Vienna, full of marble steps and chandelier and people from all over the place. The only time I came across the WFDU was in a novel by John le Carré, who'd put it as a front organization for a communist infiltration outfit in the middle of Vienna. But there were lots of people who were very straight, and it was interesting.

So Vienna, we get your agility, your eclecticism maybe, where does that frugality come from? Because you were well off in Vienna.

We are very well off. We had two nannies and there were lots of international receptions and you got on a bus, and you went away for the weekend, and you stayed in comfortable places. That was all very lovely, but in 1955, it all changed. I guess, I don't quite know. I've tried to find out, that my father was rather rude about Stalin and so, we were suddenly ejected at very, very short notice. There we were in Clapham, which was a bit ordinary, a bit like Balmain used to be in the Sydney.

"Don't go to Balmain, you'll get your head kicked in," when I first arrived, they said. Now it's very posh. Similarly, Clapham, it's now called South Chelsea by some people. But anyway, they bought a house for two-and-a-half thousand pounds. My father was virtually unemployed, and my mother, who got a job actually working, I think, as a head assistant to some outfit in St. James not terribly far from the Royal Society building where I stay when I am actually in London. She had a breakdown. Neither of them was earning and things were very, very rough.

When my father died when I was 18, we had virtually no income because she didn't have a widow's pension because she wasn't married. I developed what Br'er Rabbit in the legend, in the fairy story, talked about being born and bred in a Briar patch when he was thrown in there by Uncle Remus or whoever it was. I was used to that kind of severe austerity and coping and so if you tell me that I have to make science shows in the garage where I'm sitting at this very moment with no visible budget, certainly no reporters, or people to do research. You know, I've got a friend called David who is my producer in Sydney, and we cope.

Yes. Robyn, the man today, if you look back at your parents and you think what you got from each of them, what would it be?

Well, starting with my mother, she was exuberant, she spoke several languages. She had the most extraordinary lateral thinking. Many times, she would make jokes by verbal association, which I could not understand, and I find myself doing exactly the same thing these days. And when the mad things, I mean, just to illustrate, if you read a book by John Lennon…it's called Spaniards in the Works, not Spaniards in the Works. You switch things...it's a bit like Kathy Lette these days. That's the kind of humour that she had, and she was wonderfully social.

She would be making friends with all my other buddies and she was absolutely terrific like that. However, she was very vulnerable. When she'd broken down, all she did was sit in the kitchen, smoking cheap cigarettes and making cups of tea, waiting for people to turn up and showing no inclination to go back to the rather senior jobs that she had before as a translator, as a person who was traveling, used to meeting lots of professional people. She used to fight terribly with my father, which I hated. And my father was very strict.

He came from a tradition where you were told off, you were put in the corner if you misbehaved, you were given corporal punishment. He was very strict like that and a formidable personality, and what seemed to me from a young age, almost a genius at science. I remember sitting there one day trying to do homework of a particular physics, or was it mathematical question? And I said, "Look, just look at this." And I read him the question. And before I finished, he gave me the answer. This struck me as almost like magic.

It made me feel that there was a kind of human being, mostly male, it seemed then, who just had a natural aptitude to this, a bit like playing the piano or doing ballet that was beyond normal people like me. He also used to tell me a lot about my failings. That, obviously, I had been an unexpected child, I infer. And so, there was a kind of resentment that I inferred. For me, several things came from my father. On the negative side, I had the automatic feeling that if there was something that involved analysis of, say, a mathematical question or even a puzzle, I could not do it because he told me so.

Secondly, it was something that made me feel about some rather severe men, especially from that generation, which was to be feared. So, I learned to fear from him. But on the positive side, I also learned Welsh exuberance. Him singing Welsh songs in the original Welsh, of course. It was just incredible. When once there was a British science meeting in Swanzey and I found my way to the Dylan Thomas House that was, at that time, being restored by an engineer. And I knocked on the door and asked, I said, "Could I have a look around?" And he said, "Of course."

I said, well, after a look around, "Could I come back and record something? I'll try to make it into a science show. You're an engineer, aren't you?" But what I did was a kind of anthropological thing. Why did Dylan Thomas live in that house? And one illustration was that when we went to a toilet, the engineer showed me the wonderful toilet as it was when they first moved in. And I said, "What's the significance?" He said, "You must understand that there was lots of cholera."

Having proper plumbing meant that Dylan Thomas was more likely to live than die as a young person. Then we went downstairs and there was the living room and there was virtually a record player with a great big trumpet sticking out. He put on a song that was there and I recognized it instantly, [inaudible 00:15:16], and as he played, I could remember the words from my father singing after decades. They had an influence, and I'm still discovering how deep it went.

Yes. So, the science, it, wasn't a direct line to science, looking at bits and pieces of your bio. When did the idea of being a broadcaster, specifically in science, how did that happen?

It happened very simply. It happened when I was 12. Because in grammar school, as I then was, I'd been to the Gymnasium, which is like a grammar school in Vienna, and I'd passed that exam and that was fine. Then we got to Britain in South London in 1955, and I went into the first form in my grammar school. Then at the age of 12, you had to choose between the arts and the sciences. And it's a bit like in the old days, when women had to do what their husband said, you were Mrs. Alan Finkle, you weren't Elizabeth Finkle, or even with your first name.

Similarly, they asked my father what I was to do and he, being a good old fashioned socialist, feeling that science and technology was the way of the future. That's how we build the Promised Land. I was put in the science form. Even though up to then, I'd been very, very well performing in the arts. I could have just walked through doing languages because I already had fluent German. I had quite a chunk of French at the same time.

But there, clunk! I was in science in the very area where if you give me the exam, I remember what my father said to me about not being terribly good at things and I would freeze up. Anyway, I continued in the science and realized it was nature, the science of my body, the science of what's out the window with all the trees and the animals. And I then having looked carefully as scientists do and selectively and exuberantly, at all there was to be enjoyed, I then relished finding out how it all worked and what I was good at and what I was not good at.

And so, science came that way. Once you are doing science in the old-fashioned grammar school set up, they have ... I'm not sure they've got it now, but they certainly had it then, you did it until you were 18 and only later would you possibly change, as a couple of my friends did. One of my closest friends, actually, was doing arts all the way through and then decided, oh no, his father happened to be a scientist, so he changed to do science and got himself into bloody Oxford. Now he's the emeritus professor of public health there.

It wasn't a straight track to science broadcasting. Now somewhere along the way, you come to Australia. I guess you're backpacking to see the world and you end up on the snowy mountains project and in the mint. Put together the stepping stones of how you got back into science broadcasting?

Well, I came to Australia twice. I came, first of all, in 1964 and I came as a 10-pound pom and I was 20. My father had died nearly two years before and we were having such a rough time with no income. My mother, in a pretty dire state, terribly sad, terribly emotional, uncertain, worried, she thought the house was going to be taken away because the mortgage hadn't been paid off and still no income. My brother and sister were partly going feral.

In fact, my sister eventually ran away to Gretna Green, Gretna Green, where you can get married at the age of 15. She ran away with the lodger. It was all pretty grim stuff. However, when you get on a ship having paid 10 pounds, you arrive in Australia and you had a completely new life.

And why Australia? What was your fantasy of Australia?

I mentioned the boy who then became the Professor of Public Health at Oxford, whom I still know and love the family. As I was straight from Vienna into the school in South London, South London, as they call it. I was rather shocked to find that none of the boys had been anywhere or done anything. I didn't realize because through my arrogance, that it was partly because they came from single families, single mother families, because there had been a Canadian or a Polish pilot or the father had been killed in the war. And they're all pretty poor like we were.

But there was one extraordinary boy who was first at everything in every subject and who was captain of cricket, the fastest runner, and brilliant rugby. He also had the most fantastic younger sister, which another story. I adopted Michael Goldacre. Michael Goldacre was 11 and I was 11. And he took me home in a rather different way because I don't think he particularly knew how to have buddies, except to make me useful. Even though I knew nothing about cricket, he bowled at me, and I fetched the ball for hour after hour.

He was telling me the most extraordinary set of figures about the Australian cricket team. I thought, how on earth do you know all that? And it turned out that his family was Australian and that his father had been on television, working for the Chester Beatty science organization and developed various extraordinary things. His father was a superstar and had also been selected for the Australian Olympic team in the 440. But that's, of course, cancelled by the war. There was no Olympic games that year, so he didn't get to run.

His mother, and this is the key thing, one of the most extraordinary women I have ever met, Patricia Mary Murray Goldacre, with a wonderful Oxford accent, wonderfully kind, and it turned out - and this I didn't know till much later - the great granddaughter of Sir Henry Parkes. Australian royalty, in other words and their household was a wonderful venue for all sorts of people. Many, many professors from Australia who turned up in shorts, wearing funny hats, men and women, all wonderful at sport, wonderful at conversation, artistically minded.

I thought, well, a country like that, most extraordinary. She was also behind the invention of the campaign for nuclear disarmament. I would be in this house in Balmain, which was so enlightened because as she divorced her then husband, Michael's father, she got various boyfriends. And when she was finished with the boyfriends and including her husband, they all moved up this terrace house to a different floor. They were all there, and one of them was helping organize the campaign for nuclear disarmament.

Sometimes I'd go into the hall and the phone was ringing. I'd pick up the phone. "Hello? You want Pat? Alright, what's your name?" "Russell." "Pat, someone called Russell for you." Russell? Bertrand Russell? It was. I thought Australia was one of these places, which is not only Shangri-La, because I'd seen the odd film in Vienna of the Elizabeth and Philip visit in 1954, or whenever it was, and everything was perfect. Sun was shining and wonderful animals, and there were ads in the tube over your paying 10 pounds and you just went there.

I applied, I was accepted, and I got on the ship, the Castel Felice, the Castle of Happiness. I was given a job by big brother, and it all worked wonderfully. Grace building, which is now Grace Hotel, a very posh hotel, which is where I did my clerical job/ Around the corner was the Royal George Hotel, which turned out to be the headquarters for the push in Sydney. In other words, the push from the University of Sydney and various other organizations of one of the most radical outfit, Germaine Greer, PP McGuinness, the Hughes brothers. I really landed in the centre of something quite wonderful. Then went to the snowy mountains and the plan I'd had was to hitchhike back after two years, which I duly did.

Just as a labourer at the snowy mountain?

I was a pick and shovel labourer. Yeah, that's right.

Right. But in Sydney, you'd been working for the mint. Is that right, as a clerk?

Well, I worked for two organizations, the Repatriation Department at first, which worked out pensions. I also worked for the Decimal Currency Board or the "Dismal Guernsey Board" as we called it, dollar bill. You remember dollar bill in 1966, the 14th of February? They thought vaguely because I'd done A level science that I knew something about numbers and cash registers and that I could organize the compensations required for people owning grocer shops and restaurants to get them compensated for the conversion of their cash registers.

Anyway, I hitchhiked to London, got into the university, and did a standard classical biology course, botany, zoology, a bit of chemistry, and passed. And while I was doing that, the person I'd come to Australia with ... Sorry, come from Australia was someone I married in a very casual way, Pamela, who'd been a person organizing concerts in the ABC. She got a job via some friends of ours in London, working for Lew Grade, who ran ATV, very famous person in show business. His brother used to run the London palladium. She got a job as a casting director.

You possibly remember way back the series, The Prisoner with Patrick McGoohan. Anyway, when I was at university, I wanted to earn money because we were still poor, you know, a classical Williams tradition. So, she got me a couple of agents. Instead of digging roads, I could do stuff on television and for five years, I was a student. I did about three gigs a week, which is why I wonderfully missed so much at university.

You must have been pretty good.

I was human prop. I learned reliability. You turn up, that's 90% for junior stuff. You turn up, you work out how to put the whistle through your uniform if you're playing a policeman. You learn where the furniture is, so you don't fall over it when you're entering the Bridgerton Palace or whatever it is. And so, I did that for five years and I learned that I could not act, but I could pretend to do little bits. I had loads of different experiences with five programs, Monty Python. I missed the birth of my son, Tom, because I was doing a gig with The Goodies.

I was playing a trombone and pretending to be in the Salvation Army. That experience of doing science, a general science degree, which I thought was far too general, but it turned out to be perfect for a journalist because you'd vaguely heard of everything. You didn't necessarily understand it, but journalists don't need to understand. They need to ... The key question, what I don't understand about this is, and so being slightly bereft when it came to the powerful learning was made up for by the fact that I was such a generalist. I qualified, I got my degree and just as I got my degree, I met somebody called Jeffrey Burton.

Jeffrey Burton, I'd vaguely known in Sydney. He turned out to be a cameraman working for the ABC, the news cameraman and then later, he became the director of photography for a film called Storm Boy with David Gulpilil. He asked me the classic question that you get when you're 28 and you've just graduated, "What are you going to do now that you've grown up?" And I said, "Vaguely, oh, I'm going back to Australia, going to muck around, hang about."

He said, "I understand that Pamela is about to have a child. You need to have an income. What are you going to do?" I had no idea. He said, "Look, you've done science. You've been in TV for a long time. You've got the background there. Why don't you write to Humphrey Fisher, who is head of special project features or whatever it's called, he's at St. Leonards in the ABC and see what happens." I wrote to Humphrey Fisher and of all things, it wouldn't happen today, he replied and said, when you are in Sydney, come and see me. We landed, we got a place to live.

And I went to St. Leonards. There was this very lush person, terribly posh. His father was the Archbishop of Canterbury who crowned the queen. His wife was Dina Fisher, television and all sorts of stuff like that. She used to be on the panel of New Inventors ABC. Anyway, there he was being lush, and he said, "That's interesting. You haven't done any broadcasting. You've only been a bit of an extra. I tell you what, come back in 10 years when you've had some experience and you've written a couple of books because that's the standard these days."

I got so cross. He reminded me slightly of my father, this male determination authority, and he'd been writing various things. Imagine you've got butcher's paper. He'd write something in the middle of it. And I said, "If it were me, I'd have written on that page, just one page, not all this stuff that you've been scribbling on." I was actually telling him off, this person who I went to see to get a job. I was telling him off. He looked rather startled. And I then dropped a few names, I can't remember whose. But before you go to a place, you case the joint.

I mentioned a few names to give him the impression that I knew roughly what was going on in the ABC. He wrote on the remaining piece of paper, he dare not take a fresh piece of paper, slum child again, and gave me Peter Pockley's address in William street. Peter Pockley was the head of the Science Unit, which then was mainly responsible for radio and not television. He'd done some television, a couple of amazing programs, which were international hook-ups. But anyway, I left that appointment with no idea particularly what I was going to do.

The following week, 50 years ago, I had two appointments. One of them was in a girl's school, somewhere in Sydney. And somehow, I don't know whether it was via the labour exchange or whatever you call it, Centrelink. I'd been sent along to see a ... Turned out to be a Padre. And he said, "Yes, you can be a teacher, but don't drink at lunchtime and you'll be teaching geography and maths." And I said, "Well, I haven't done math since God knows when," which is the wrong thing to say.

"I'm not terribly great on Australian geography because I haven't lived here very much." "Oh, that won't matter." The other appointment I had was with Peter Pockley. Here was this amazing person who'd been one of the head boys at Geelong Grammar, who'd got himself a Rhodes Scholarship, went to study at Balliol in Oxford and had been a teacher himself. In fact, he'd written a textbook of chemistry. When I dropped my names, he was most impressed, people I'd been reading, the people I knew in Sydney who were vaguely connected to science broadcasting.

And he said, "Well, we happen to have a couple of vacancies and we've got Apollo 16 and 17 happening this year, 1972. And we need someone who can get some stuff together." I was being offered a job, much to my astonishment and that's how I joined the ABC. I was kept on to do that sort of thing and gradually discovered what broadcasting was all about.

Your initial job involved being a researcher?

I was a gopher. Yeah, I was a gopher. He said, “how tall is the Saturn rocket that's going to take these three guys to the moon in April 1972?" And so, I said, "Oh, it's as high as the AMP building," which was good to say because it gave people an image, and it was short and sharp and to the point. I gradually learned how to do that stuff. I was also being taught editing and it was quite extraordinary because here was the ABC science unit, full of people, I immediately recognized as really top class.

I mentioned Peter Pockley's background and he was a wonderful live broadcaster. There was a bit of ruffian called Michael Daley who had started doing something called The Daily Weekly or The Weekly Daily. I can't remember the one way, in New Zealand and he was a classic lunchtime booze person. I don't think he had a degree, but he loved science and he was really a person who could chase down the hot story. There was somebody called Robin Hughes, who's better known to some people as Robin Throsby.

She was a person of immense intellectual quality. She's been the youngest person ever to be hired by the BBC Third Programme, come from a really great Australian family, obviously. Margaret Throsby, her sister-in-law, David Throsby, Professor David Throsby, her husband, her daughter, Edwina, is now head of some very important part of the ABC. She taught me how to be succinct, how to be focused, how to edit. My first piece of editing was of One-Tree Island on the barrier reef.

And One-Tree Island was being experimented at, by Frank Talbot, who is then director of the Australian Museum. He was putting artificial reefs there to see how quickly with that kind of artificial structure fish moved in. And there was the tape I had and there was the razor blade and the little marker. I learned how to cut the actual tape, although he didn't need that much. He was a very precise speaker. I learned that ums are about that long, half an inch, and they got spaces either side, you can cut them out very easily without any bumps.

It was interesting that the science unit was also a place where you could be against the regular rules because we were not supposed to be doing the editing that was supposed to be done. We were a part of the GPO. We're part of the ... Our minister was the postmaster general and so the designation in the commission, the ABC commission, was fairly strict. It was tech who was supposed to do the editing and not us. But we did it anyway because it's so much faster than going up the road to a studio to dub off an arm.

Let me get you straight. You talk your way in, bluff your way in, basically, by insulting whoever that guy was, telling him off of taking up so much butcher's paper, why couldn't he just succinctly get down the message. Then you managed to impress Peter Pockley? It's not like this was your driving ambition. Your other option seemed better than teaching geography for a non-Australian. And suddenly, you're in? You've charmed your way in somehow?

Yeah, because I had the confidence of impermanence. I was only supposed to be in Australia for a year. I was going to go back and do something for the BBC. Because with all that experience as a kind of walk on prop, I thought I could bluff my way into the BBC. It was quite interesting. We did, in fact, go back to London after a year, it was more than a year, actually. All my gear was on the ship, and I was still doing a bit of interviewing because I thought, well, you never know what's going to happen.

The aforementioned Robin Hughes left a message in the ABC London office. Would I please phone Sydney? I thought, what on earth is this? I'd just been to the BBC. I talked to, funnily enough, somebody else called Fisher, who was head of the BB[C] and it was so dull. I found them pompous. Does he really have a powerful mind? Which college was he at? Blah, blah...and all that stuff. I didn't want to know about that stuff. I wanted to know about the big ideas that they were talking about in Sydney.

And so, suddenly, I thought, oh, well, there was Robin Hughes on the phone. She said, "We're starting a new program. It's going to be called Investigations. It'll be on from 7:15 in the evening until 10:00. We're going to have it all live. We're going to use the new satellite connections that we can get to interview anyone in the world who's willing. Will you come and host it?" I then phoned the docks and said, "My luggage is about to turn up from Sydney. Would you please turn it right round and send it back again?" I went back to Sydney and that was a commitment.

And really, the people there in the ABC all-round, the Collection of Baroness. It wasn't one great big lump of the ABC. It was lots of barons who ran music, who ran drama, who ran science, who each had their empires and did extraordinary things. One of the most extraordinary was Alan Ashbolt's empire of talks. It was called special project because he was very left wing, and that was the basis for the classical antagonistic of the outside, some parts of it, [see] the ABC as being a left-wing plot. But he was very don-ish.

He was left wing and thoughtful, but in the best of all possible ways. He'd been doing four corners and had criticized the RSL and you didn't do that then. So, here was an ABC that was able to innovate because it had very, very smart people. It had hired the best, the people who were senior there had written books, their plays were on around the country, we had orchestras, we had a natural history unit that then worked with David Attenborough and the BBC One. It was really a class action.

It sounds that your passions for communicating science and public broadcasting suddenly were formed in this crucible. You didn't come in with - "I want to work in public broadcasting because of my enlightenment project for the world". You came in pretty much just this hobo off the street?

I needed a job. I'd worked in factories. I'd dug roads, I'd dug tunnels, I'd done all sorts of things. One of the things that was different in London, in England, there was a class system that implied from a very young age, you were essentially not qualified. Only by a fluke my buddy, Goldacre, got himself a place at Merton College, Oxford. That was extraordinary, my gosh. Whereas in Australia, not only was I temporary, but I could muck around it. It was if I was somehow in an impermanent place and could experiment.

It didn't that much matter until, of course, it did matter. Strangely enough, having started the Science Show, in the science unit, there had been the aforementioned Michael Daley who did a magazine program. That was, I think, the World Tomorrow, which is a half hour and is on Saturday mornings and it had lots of innovation stuff. It did a certain amount of journalism, but it was very much information based. It wasn't so much fun, and I had been swept up with the people I described in the ABC who invented something called the radio action outfit, which met in a church in William Street, heads of department, all sorts of people.

They're the smartest imaginable, all experimenting with bright ideas of what you could do. So when things changed and things became possible, we took off and our contribution was to invent something called the Science Show, which was going to be a program, not as buckets of information, but of ideas, and which depended on being out there, not in your office, not at the end of some sort of remote connection, but looking out at the world and then reflecting it as it really is, nature as it really is, science as it really happens to be.

Need I say that these days, I still do that and I'm looked upon with certain amazement. Tomorrow, I'm going to do five interviews, walking the corridors at the University of Sydney, knocking on doors. Hello, Professor, you don't know me, or you possibly do, and I've done that for 50 years because you find out what's actually happening out there, and you are doing so in a language that's active. The Science Show was invented. I did the first one from Canada, actually, in August 1975.

Strangely enough, I could repeat that program and most of its content would be appropriate today. However, when I went back running The Science Show till, I think, it was something like the end of '75. I did it for three years, but I had applied for a job that was advertised, a dream job for me, that is the European correspondent for the ABC to do anything to do with talks, not just science. I could do what I'd done anyway and go interview Lord Clark of Civilization, the Oxford Don who had done the first ever series of 13 programs on television. I could go to Austria.

I could go to all sorts of places to do interviews. And then there was an election because Gough Whitlam had been dismissed. It's quite interesting because I was confirmed on December the 2nd 1972, having done that year as more or less a freelance gopher on a semi-permanent basis. In December '72, in came Gough Whitlam. Then at the end of '75, there was a coup, out went Gough Whitlam. Fraser came in and as usual, the first thing that the conservative government, the Liberal government, Malcolm Fraser's government did was chop the ABC budget.

The first job to go was the one I'd got to go to Europe to be the talk's officer, hence The Science Show did not stop at the end of 1975 or be carried on by somebody. There I was, and it continued. Fate.

Just a minute, I'm a little bit confused. Because you went from being a gofer to doing investigations and then the Science Show began in '75, right?

I turned a gofer into being an anything. Because as I said, we did our editing, even though we weren't supposed to. And I turned out to be pretty good with a microphone. Because during Apollo 16, I think on the second day, Peter Pockley left the live studio where he'd been on for hours, from dawn. And he just said to me, "Go in and take over." That was my training. I found there was a sort of phone in thing. It was actually an army telephone with a switch on and off.

I had to do an interview with the speleologist or the selenologist, the person who understands the rocks of the moon, who's at the ANU. I managed to connect it and I interviewed him, and I kept on saying, "That's interesting. That's interesting." Anyway, after several weeks of improvisation, I then was given my own little program called Innovations to do as a presenter and then we invented the Science Show, but the Science Show came three years later.

Peter Pockley had spotted that I might have a certain amount of flare and gave me a job at the end of 1972 to do the Commonwealth Day documentary program, which is to go to 32 countries, which is on the building and the finishing of the Anglo-Australian telescope on Siding Spring Mountain. And so, as usual, I track down all sorts of name drops. I found Fred Hoyle, the famous astronomer, who should have gotten a Nobel Prize for working out where the elements come from, cooked in stars.

But did not get one because he had the wrong idea about the nature of the universe. And all sorts of other people whom I interviewed, including the Professor of Astronomy at the ANU, who was vaguely in charge of the Anglo-Australian telescope construction. We got the age of the universe wrong by a factor of 10, which I thought was very interesting because he got billions mixed up between American ones and other. We broadcast that to 32 countries, and there was only one complaint.

There was my documentary, and I'd been there up on for a whole week, a week on location. This is luxury, interviewing the astronomers and also, I interviewed mainly men who were building this fantastic telescope which, for a period, it was the best in the world. The people I talked to who were the workers, if you like, the engineers. The engineer actually said to me, "We had this most wonderful incident when the workers, the mainly Indigenous men heard that the British Minister for Science and Education was coming out to inspect and they thought they'd build an Aboriginal embassy to welcome her." Can you guess who it was? Margaret Thatcher.

Oh, okay.

I had that in my documentary and that was a bit that Peter Pockley demanded to be cut out because you can't have that sort of thing going round to the Commonwealth on a Commonwealth Day program about something so pristine as science. By the end of '72, I'd done so much broadcasting. I was on air all the time.

Your broad science degree and your theatrical training and your natural every man or every person just expressed itself in the Science Show. It really is still very much the character of the Science Show, as I reflected. I love to listen to the Science Show. I listen to it as a lass and I think, well, there are so many science programs out there, but I still like to listen to the Science Show. I like its character. I like its eclecticism and I guess I like that sense of this is for the every person, inserting myself into labs or just putting my finger to get the pulse of what is happening in science this week.

Let's talk about the evolution of ABC Science. As I say, when I was a lass, all I knew was Robyn Williams and the Science Show, one of my favourite activities on a Saturday. Now there's lots of different programs on science. Is that a good thing?

It can be. On the other hand, if you talk to someone like Merlin Crossley, who's Deputy Vice Chancellor at the University of New South Wales and a scientist, or if you listen to someone like Sir Paul Nurse, who's the former President of the Royal Society and a Nobel prize winner, both of them say, we are drowning in data. You have material coming at you at such a rate and in such a fashion, it's almost impossible to digest. When I did the program, the one thing that I found absolutely delightful in the beginning was that there was no shopping on Saturday afternoons.

People came home at 12:00. We no longer had scratch records being played. The couple of science programs had been on somewhere else doing innovations or something, how the latest widget works, but the Science Show was supposed to be about ideas. There was information. Yes, you can't do without it, but it had to be in this structure of narrative experience and some sort of excitement. It could be excitement about something horrid. We had horrid stuff, yeah, sure. Vacancies. We had quite a few vacancies despite the job cuts that came later.

And there's this Scottish chap, a doctor called Norman Swan, and we asked him what he wanted to do. Obviously, he wanted to do a medical program. He said, "Yes, but I also want to take on William McBride because there's something scandalous there. And we all know what happened to the person who was very, very famous for exposing aspects of drugs being used badly and thalidomide and so on. Who was eventually, through Norman and the Science Show, dismissed for seeming to fake his research. One aspect of it to do with an after morning pill.

We had all sorts of stories. We had long ones, we had short ones, and we wanted to be flexible in that you needed roughly a short item, could be five or six minutes. A longer item could even be the whole program vis William McBride. Or you could have a series. I remember when Johnny Merson, who was one of the people who was hired to be with us, who had been on television, John Merson, who's now at the University of New South Wales and a wonderful lateral thinker.

He kept on saying something about the Chinese and Chinese history of science and if only people realized how much the Chinese had invented in the first place, but they didn't know about it themselves. There's this professor at Cambridge who's written, I don't know how many books on this. "We really ought to do something." I said, "Johnny, do you think you'd need a whole Science Show?" He said, "No, six." Six site shows. "Why?" "Well, I'd go to China, or I'd go to Harvard, and I'd go to various other…" Oh my god. And he did that. And he came back ...

And you had to pay him.

And we paid him. We had funds, you see, money, money and he came back with this stuff, and it was a most extraordinary discovery. Here was evidence that was gained through a colonial means. These people from Britain had been in China, more or less in charge of stuff and as they came back, and many of them were thoughtful, they'd written up how much was there in China, if only you went to look in various places. And putting it together was one of the triumphs of investigation.

Johnny put this stuff together and we had the main people in the field, in the world, in our programs and we broadcast it. It was fairly routine until a couple of years, few years later when I decided, because our attitude to China had changed, I decided to rebroadcast them with slight amounts of editing. I happened to be in ... I think it was Brisbane and Simon Winchester, the writer, just published a book called Bomb, Bang and something else. And I said, "Gosh, that's interesting. We did a series of programs on that." He said, "Oh, really?

Because we could not get near half the people." I said, "May I send you the recordings?" And I did. And it was just euphoric because we had been out there and done it. We had science as history. We had science as narrative. We had science as politics because that's what it is. We weren't inventing it and to make science just what is published in journals and here's a summary...one of the arguments I have these days, because most of the people who are doing science, we've lost the natural history unit that went some years ago.

We couldn't make Nature of Australia anymore like we did in 1988. We've lost the connection with what my partner did for 20 years Catalyst, which was a half hour program for 38 weeks a year, half hour program with maybe four or five items. And again, variety. Most of the product that we have now is scripted stuff, mainly to do with information, mainly to do with the new cycle, what is published, what's out, what's topical and of course, the public don't know about topicality. Well, if you land on Uranus, that would be topical because it never happened before.

If rocket blows up or if there's a volcanic explosion in Tonga and a tsunami, yes, yes, yes, that is now. Whereas most of the work that we cover and that is covered in news about science is to do with the publication. It's semi what we call what, in fact, a colleague of mine in the United States, science journalist called spoon-fed journalism. You are at a conference and there's a media centre and it's all timed with an embargo and it's to do with the publication, not the fact that something is happening.

When I walk the corridors, I'm doing work in progress on the basis that when you hear it in my program, and then again when it turns up, you'll think, ah, I knew about that before and now they've got to this stage, they've managed to publish the fact that they've discovered the whatever it is. You ask a question about whether everything is fine because it's so ubiquitous. Well, stuff is ubiquitous. And as I said, we're drowning in information and I'm not quite sure what that means for me personally or the future of what we do.

I know people will keep churning stuff out there, but I talked to you as someone who did a brilliant job of editing Cosmos Magazine. I was told the other day that there are more magazines dealing with tattooing than there are dealing with science. I don't mean journals. I mean magazines. I can think of Cosmos, and I can think The Skeptics Magazine. It's a bit of a struggle already, but most of them have gone. I haven't written an article for a magazine or for that matter for a newspaper for years.

Yes, it's tough, commercially tough, which I know from experience. Maybe we had a high point at the ABC through the late'70s, even maybe the '80s. But a definite low point, truly shocking to me, was the axing of Catalyst. When did that happen? I think in 2016 or something like that. And you didn't pull any punches, Robyn. You wrote - "this week up to 17 catalysts staff will leave the building. One of the top teams in the world dedicated to science communication, absolutely. With not a farewell, a handshake, or a stale biscuit but like felons out onto the street." I cannot understand to this day what happened.

Oh, it's very straightforward. You had staff broadcasting on air and you've got that in news, yes. But as a very nice person who was for a period, the Director of Television, Sandra Levy, said to me once and said to colleagues, "Here you've got a standing army of broadcasters, but they're not broadcasting because we don't have the budget to make the programs. The standing army still has to be paid salaries because they're permanent. It doesn't work. Either we've got money to make the programs or it's not on."

And always, they've been tempted by what happened overseas. That is that you've got outside companies making programs which the ABC could buy or not buy. With radio, it's more difficult because you need people who are skilled specialists and they're not lying around much. You've got people who could write about science, but they're not necessarily broadcasters. We, in radio [are] broadcasters, and you can ask us to go and do something fairly cheaply. And here I am in the garage in some part of New South Wales still doing it. I've done two interviews this morning.

I'm doing five tomorrow. Television costs money in gear on all the rest of it. They'd already shut down the natural history unit, despite the fact that we'd done Nature of Australia, that was a co-production with the BBC where we did it all. But they broadcast the program first, strangely enough, and got 8.2 million people for the first broadcast on BBC Two, that's a television network. And when it came to cutting down catalysts, they got rid of 17 people.

All you need to do is appoint a couple of people who would then be the commissioners, if you like, and working with people on the outside who run independent filmmaking or TV making programs. And nowadays, they do it, not necessarily by going out there. You probably notice this yourself that what happens is the ABC has a vast archive, all those years going out and filming in the bush and all the off cuts or the things that you can use in a different way.

You go to the library, you take out all shots of nature, kangaroos, camels, you name it, the rockets being fired into space, all the action that people did for so many years. You then do a new program with new talking heads, with off cuts from this library stuff. And it's so much cheaper. You don't have to pay, unless they're superstars, the people who are going to be on air as talking heads. You've got all the other stuff in the cupboard, which you can give to the people from the independent filmmakers. And there you can continue as if you have local content.

That's how you deal with massive cuts. The strange thing is I remember interviewing David Attenborough when he came out at the launch of Life on Earth. "Oh, you've been to all the continents on earth, that's astounding" and some people said that's so indulgent. Now all that travel and all that waiting round for the polar bear to turn up and he said, "Look, if you do something, that's the best. And it's known as the best because you can see it. It's got the best science, the best people, the best shots of animals behaving in a way you've not seen before.

And do you know you can sell it just as much and easily as you do the old stuff? You amortize the costs, and you make a fantastic reputation for doing it well. It's not squandering money, it's investing it." That was David Attenborough's answer. And he's quite right. It seems to me that the way forward would be to understand as you could with science in Australia itself. And what are they doing? Two things. One of them, they're not investing in basic science, which is the food stuff of translation or applied work. If you don't have the basic science, you can't do the applied work.

Secondly, when two people who I've interviewed in the last two days, for example, who've just graduated with their PhDs, do they have job in Australia? No, they're going overseas. There aren't more than a handful of jobs in Australia and science and technology Australia, the organization that represents scientists will tell you that one in four grants can be given. In other words, contracts for doing work and they are each worth only 18 months security. That is what's being offered someone who's worked all those years, done, not just a degree, but a PhD and is ready having cost the state a million dollars in education. They don't have a future. Now the same thing can be said for Australia, a rich country's neglect of science broadcasting, which I think could be doing some fantastic things.

You haven't pulled punches with the attrition of the ABC in 1978. Actually, the ABC turned off transmission in industrial action and must have been an atavistic time for you recalling your father. And what did you do? You said I'm sick of watching the ABC fall apart, I'm sick of waiting for one public statement of concern from Mr. Norgard, of waiting for the smallest, the slightest action from him, or indeed senior management to show that they're doing something to save the ABC. This was at the time of the cuts by the Fraser government. The ABC was haemorrhaging.

It's been haemorrhaging for a long time, and yet it's still here. How is the patient today? Notwithstanding the assaults from technology that have made it very hard to compete, dismemberment by various governments and economic rationalism. How is the ABC today?

It depends, really, on the nature of government and I don't mean left wing or right wing, Labour or Liberal. I mean, by whether the government itself has goodwill and a sense of the future, this latter seems to me exactly what's missing. Yes, I said those things in 1978. And the minister was Tony Staley. I'll give you a couple of examples of our being outspoken. And, yes, we had some sort of idea of what we could be doing, partly because we were already doing it and had been stopped from doing it.

We knew that the public wanted programs that we made because we were in touch with the public and there was good feedback. There was an arbitrary cap. We protested, and I remember there were really hot discussions going on between our leaders as broadcasters and the people, the authorities, which were top of the ABC, Sir Talbot Duckmanton, and other people like that, and the conservative government. And when it was settled, there was goodwill.

I know there's goodwill because you see, even though I said rude things about the top of the ABC and Tim Bowden, similarly. When we had a party in the science unit, we invited the whole of the ABC up William Street from all sorts of departments to come along and we had a real riot. Downstairs that just invented Triple J, which is then called Double J, and they came up as well. Marius Webb, who was the person who launched Double J, was the subject for the strike, the staff elected commissioner. They didn't want him. Anyway, we kind of won.

So I invited the commission, that's the board of the ABC to come to our party. The aforementioned Norgard of BHP fame and so on and Leonie Kramer, who was Deputy Chair and a very conservative person, the person who went on to become Vice Chancellor of the University of Sydney, they all turned up. Can you imagine? They all came. I proposed a toast to the staff elected commissioner of the ABC, Marius...and they raised their glasses. There was goodwill.

To some extent, I'm reminded and I'm not being romantic, of Chifley, having a scotch with Menzies, even though they were on opposite sides and leading two different parties. When he came to Tony Staley, Tony Staley, the Minister of PMG, in other words, Post Office. We were still not quite in the corporation. He had a terrible accident and was in a wheelchair afterwards. This is years after the strike, and we became friends. We got on very well. He was telling me that his son was studying physics and he'd been listening to our programs. And I said, "Where is he now?"

"Oh, he is in America studying Einstein's work on physics." "I must look him up." I did, and I broadcast him. This is goodwill. At the moment, the Nature of Australian politics is bilious. It's opposition at all costs, with no sense of the future. And this is what worries me because it seems to me that one of the great things that a Minister for Science, whom I really treasure and he's just turned 90, Barry Jones, he invented the Commission for the Future because he'd written a book called Sleeper's Wake. In other words, this is the science of the future. This is what's coming.

He was talking about the new technology and manufacturing that we should do. Instead of depending on another country to send us widgets, does it remind you of anything? Computer revolutions, for example. He was saying, "We should do it. We should wake up." Sleeper's Wake. And he invented the Commission for the Future so that we could encourage Australians to imagine what they would like their future to be. Would your school have a teacher standing in front of the class and would you have desks in the normal way?

Nobody imagined we would have iPads or anything like that on those desks, but imagine what it will be like, imagine what your shops would be like, imagine what the agricultural world would be like. For a while, we were able through the Commission for the Future. Then Philip Adams was the first Chair. I was the second Chair. John Button of great fame was a person who came after me, and we tried to excite people's ideas about the future that they wanted, the Australia that they wanted as if it was obtainable.

Of course, being obtainable means if you develop the science in a proper way as a vehicle for change as something, which would enable you to live differently and better. I don't see any of that in the current election discussion. Science, as far as I can tell, has not featured. People are talking about translational work, as I mentioned before, but not about the basic science. It seems to me also that the ABC has been left in that kind of no person's land, which is why the ABC alumni are campaigning and have been in the press.

And again, have been attacked, especially Jonathan Holmes, who chairs it, has been attacked almost every couple of days in the Murdoch press. This is greatly worrying. We're not in a war, we're in a society, and a society should combine despite its different cultures and ideologies to look at the way the future can unfold because the future is looking very, very dodgy at the moment as science tells us.

Robyn, let's move on from politics to science. I mean, you've been in an extraordinary position, as I said, drinking from the fire hose of science for half a century. Anybody would want to ask you, well, which are the stories that have fulfilled that promise of miracles and which are the stories that haven't, and who are the people that really stick out for you? Which stories fulfill the promise, first?

Of the sciences, I tend to concentrate on the ones that Norman Swan doesn't do. In other words, I don't do medical therapy and I tend not to do the straight news stories because my program is on three times a week on air and it's there as a podcast, and so an awful lot of the stuff that's announced is going to be bloody obvious by the time it comes around a week later. I tend to be not a slave of topicality as conventionally designed, but I try to do, as I said, deal with ideas.

I find it really fascinating that in the beginning, I got into terrible trouble because we seemed to be campaigning and it was mainly for the first area. In fact, I mentioned that in Science Show, number one, I had concern about forests, concern about young people leaving science, not being ... In fact, it was the publisher of Scientific American who said, "I have failed in my career because young people are leaving science." I also had an interview with Lord Ritchie Calder, warning about climate change based on the emission of fossil fuels.

He gave tonnages of each of the gases, the greenhouse gases, and that was in Science Show number one. And we have been warning about this since 1963, and here we are in 1975, and as we told the United Nations, no one is doing what's necessary. That was in Science Show number one. I got into trouble as I was about to say, because we fostered a campaign led by a dear colleague of mine about asbestos, and we were attacked for being against Australian mining and capitalism and all that sort of thing.

And we said, yes, but the evidence, Matt Peacock was on air all the time, very much in the Science Show about asbestos and working with asbestos being really dangerous beyond belief. Here we are all these years later, no one would imagine doing a promo for the advantages of asbestos anymore. Similarly, lead in petrol. We talked about the research to do with kids' brains and how lead in petrol, despite the fact that it was going to be good for a knocking engine, it would stop the knocking, make it more efficient, it was killing people.

Indeed, some people said that if you looked at the performance, the IQs, and God knows what...the scholastic attainment of young people, mainly Black people in America are kids who lived alongside big roads, highways, their measurable brain performance was lower. Then we had coal, of course, and I did an interview with one of the Vice Chancellors at RMIT University in Melbourne, and he was saying that the amount of mercury produced by burning coal is enough to cause damage to the brains of 60,000 kids, babies in America per annum.

The stuff about coal was overwhelming. And of course, still this argument [is]not scientific argument. Argument in public about whether this science is okay. I've seen what we warned about coming true in lots and lots of ways, and some of the people I talked to...I am enthralled by the young people coming up and their enthusiasm and their ability. I interviewed two today. Both of them, as I implied earlier, going to America. One, who's doing the counting of various molecules. You know, physics, it's the mathematics and physics, really, of the body and he's doing work on how it affects cystic fibrosis. He couldn't get a gig in Australia, so he was going to America. The other person I interviewed is a person who studies how lyrebirds learn their song. She's finished her PhD and she's being awarded, we hope, but she's already got a place in Cornell. I love these people, the freshness, the innocence, the way they describe it is like you used to say, find a scientist in a pub "saying it real", with the enthusiasm, not writing a scientific paper, but as it really affects their hearts, as well as their brains. That's what I love.

Some of the people I have put on the radio ... Well, talking about asbestos, I lived next to a psychiatrist who moved to the Central Coast, and he did lots of good work as a psychiatrist there until he suddenly got in touch with me and said, "I seem to be ill." I said, "Well, what's the problem?" He said, "I think I might have something like asbestosis." And I said, "Oh my god, how did that happen?" He said, "Well, I remember in Balmain, when suddenly I don't know what it was, the ceiling fell down and we had all this rubble around as we were breathing it for well over a week."

And suddenly, he had mesothelioma. I said to him...I don't know quite why I said this to him, "Would you keep a diary? And every two weeks, we're broadcasting something about what's happening to you and what you're doing about it." And we did. He talked about being a singer and he talked about traveling with his oxygen mask on the plane and his flask of oxygen and how he loved singing, even though he couldn't do it terribly well because his lungs weakened. He did that right to the end. This was real science.

It was science that transmitted a completely different view of what it was like being applied. Here was a person trained as a scientist and a professional doing the broadcasting for me, and there were several examples like that. We also had a great number of people who were biologists, who were radical. I broadcast because it's the 90th anniversary of the ABC, some of their arguments. E. O. Wilson, the idea of biophilia, he who's one of those gentle people I've ever met; a Texan who was talking about ways in which sociobiology affects people.

But various Marxists, Richard Lewontin from Harvard, they were on adjoining floors, but mortal enemies in many ways. But I'll go back to what I was saying about the politics of yesteryear. They were still polite to each other. They're still engaging to each other. But one had a view that science meant that you were flexible as a human being and the other implied that you were in the rigid tram lines of history. This, of course, was behind what I'm broadcasting this week because one thing I haven't mentioned is how fond I am of history.

This happens to be the 200th anniversary of Gregor Mendel, his birth. Mendel's work, some of the greatest imaginable. You could not want greater proof of something being shown again and again, not just by scientists and labs, but by the whole of agriculture and the breeding of animals. And yet, Stalin was totally against it, and there was Lysenko, his buddy, and they actually killed Vavilov, the person who said we needed to collect all the seeds in the world.

I broadcast something terribly poignant about the ways in which the scientists had the store of seeds collected by Vavilov in Leningrad during the attack by the Nazis. These scientists were starving, and they could have eaten those seeds, but they said, "This is the heritage of our science." And they died of starvation, and the seeds survived. This went on until 1965. The Stalinist view that Mendel was wrong and this idea that we are not prevented from building the promised socialist land, my father was used to talk about, because we had flexibility.

Whereas if you say it's all in our genes, you can't move. You're destined. You're going to be a woman as women are supposed to be and they are a capitalists. And so, Stalin rejected on that naïve basis. Some of those things really affect me, but it's the young people who make all the difference in the world. I had one on three weeks ago whom I met at the Australian Museum. I've not mentioned the Australian Museum, which is one of the loves of my life and I've been President of their board. This little kid came up to me and said, "I want to talk to you about neutrinos."

And I looked down, I said, "Why? I don't know. Where do you come from?" He said, "Townsville." "And what are you doing reading about neutrinos?" He said, "I love physics." "How come?" "It's so interesting." Next thing I know, last year, he won the Eureka Prize, the Sleek Geek Prize for the video he did. He's moved from physics, not that he's given it away, to biology, and he's done one about rewilding, why it's important to bring the top predators back. Because they will catch the moose or the deer and all those vegetarians will stop killing all the trees and all the bushes that are growing up and you'll get a greater balance in the landscape, in the ecosystem. I put him on the radio, and he talked for 15 minutes. He's 15 now, and he's sensational. Well, it was a scintillating stuff. Because he'd read the books. He dissipated my fear that young people would only look at screens. He does both, and he shows how you can actually exist well from a screen, as well as a book. You need the depth as well as the stimulation that modern technology can bring. But you need a balance.

I'm going to ask you a last question because I think that's all we've got time for. In your wonderful book, Promise of Miracles, which is just wonderful, and Alan's going to read it next. He was fighting me for it. As you say, you love history and there's just something so rich about this firsthand view of the way the world looked, particularly the way the world of science looked 20 years ago. One part that really moved me was from your Alfred Deakin Lecture.

You started wonderfully with that quote that sometimes attributed to Churchill, but probably antedates Churchill - that if a man is not a socialist by the time he's 20, he has no heart. He's not a conservative by the time he's 40, he has no brain. And this essay, you rift on the fact that when you turn 40, you were waiting to see what would happen, how the conservative spirit would take over. But towards the end of your essay, your wonderful essay, you quoted three people, I think, that resolved your right and left leanings.

One of them was Arvi Parbo, the Estonian refugee who became a mining engineer and then a Chairman of Australia's three largest companies that "you need constructive solutions to the environment", as opposed to all this ideological fighting we have at the moment and "all problems are actually underpinned by a strong economy". I guess that was your nod to turning 40 in a conservative, but you also quoted two other people, Bertrand Russell and his main motivators being love, wisdom and pity.

And Peter Medawar, who, despite all his terrible medical problems, his credo was, you stay in the race not to be in ahead, but to be in that race for human good. Robyn, in ending, what would be Robyn Williams' credo, your motivations? What are you going to leave us with?

Well, first, I'd tell myself off for having quoted only men because I'm reminded of my strange relationship with my father looking at authority. Well, Medawar, Nobel Prize winner, absolutely wonderful men and Bertrand Russell, ditto.

Who you spoke to. You spoke to him?

Yes, indeed. No, I didn't speak to Churchill. I did speak to Arvi Parbo, and I know that he was a very narrow man. He was a very good scientist and geologist but when we debated, he was looking at environmental problems as being ideological ones, not understanding the nature of ecosystems and the nature of ways that you can do so much better. I mean, coal is ridiculous as for what it's worth. In the old days, you know, my father going down the pit and having all those diseases, dying at 57.

And what you could do with coal instead, oh, hundreds of things, and there are far better ways of using it. What I would give myself as a credo these days is looking forward to, as you implied, there's always a solution to a major problem. The wonderful thing about science, two things about science, in Australia, it is now mature. Because when I started broadcasting, you didn't do terribly much science in Australia. [Frank] Macfarlane Burnet was the first person who came back to do his work, one of the great geniuses of science. He didn't just do it overseas. He came here to do it.

And also, the scientists are talking to each other and there are no strict boundaries. I've just given a couple of examples. One of them being a person who's working on the physics and maths of molecules and looking at cystic fibrosis. If you put the scientists together, you can find a solution by mixing them, because nature is a mixture. If you just live in a box, that's not real science anymore. Not that it ever has been, but we can do so much more. We can then, in terms of public policy, put real science in every department of every government, every single one.

And also, when you are telling young people about studying science, it's not to be a scientist necessarily, it's to do every single job. I think I may have put it in my book way back then, Promise of Miracles, that if the person who's making your sandwiches at the conference has never heard of public hygiene, you have a problem. If you have someone who's organizing the garbage, I went to the Nowra tip to do one of my stories. Why? Because everything on that tip was being recycled.

They had mountain of mattresses and they're taking out the plastic fibres, and another mountain of dirty glass that they were washing, putting them together and making household tiles based on the work of Veena Sahajwalla from the University of New South Wales. Putting things together, finding solutions, making science work as a unity like nature is. There's nothing I can imagine apart from keeping the earth as it is for eternity, that isn't possible given what we know. And I would say when it comes to individuals, her name is Frances.

She won the Nobel Prize for chemistry about three years ago at Caltech, and Frances Arnold is her full name. I did an interview with her. She, again, was working on some of the aspect of molecular biology, but in fact, is everything. She was looking at the future of which proteins would be developed, not just in nature, but by people in laboratories and she got the Nobel Prize on her own for that work. And she said, "Coming to my party tonight?" I said, "Oh yeah." I went to her party. In the queue, I was surrounded by five Nobel Prize winners.

Turns out, she was the first one out of 38 who was a woman to get a Nobel Prize at Caltech. She stood up, made a speech. She took out her medal, "This is the gold medal, the Nobel Prize medal that you get. I'm giving it to my staff." Then she took out the check that she got from the Swedish Academy, and she gave it to the department to do science. She then thanked everybody and caught the 10:00 plane to Melbourne to give a lecture. That's class.

Great. Great. Okay, good point to end, I think.

© Australian Academy of Science

Some re-use permitted (Creative Commons BY-NC-ND)

© 2025 Australian Academy of Science